First of a two-part series on the legacy of Hyde County’s earliest people.

Traces of history reside in names.

Supporter Spotlight

The surname Mackey, for instance.

While linguistically Scots-Irish, in the Hyde County area, Mackey is well-documented as being associated with the Mattamuskeet Tribe, said Ramona Brown.

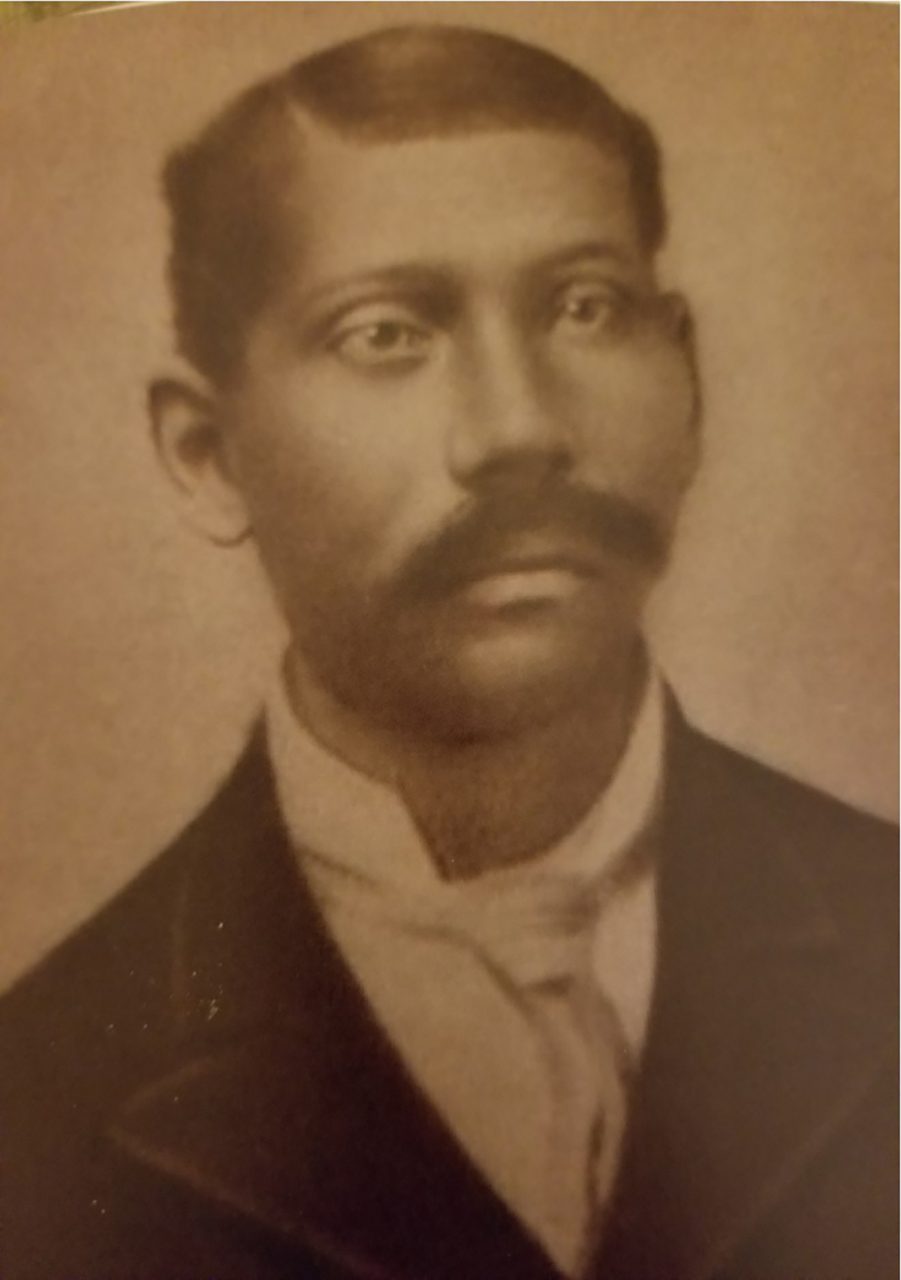

Her great-uncle on her mother’s side, Napoleon Mackey, is one of the Native Americans that archaeologist Patrick H. Garrow interviewed and quoted in his 1975 publication, “The Mattamuskeet Documents: A Study in Social History.” At nearly 200 pages, it is likely the most thorough study done to date on the Mattamuskeet Tribe.

Mackey lived “just past the lake itself in a little town called Fairfield,” Brown said. “I remember as a child going over there often, particularly on the holidays.”

While visiting him, she recalled her mother and grandfather telling stories about Lake Mattamuskeet. “Grandfather told us — he was born in 1904 — that that lake was actually dry land, and he said that his ancestors … actually were able to walk on that area. And over time, it became a natural lake.”

Supporter Spotlight

Brown, who has worked in journalism for 40 years, noted that when she researched the history of the lake, what she found backed up the oral tradition her grandfather shared. “That was interesting to me,” said Brown, who grew up in Beaufort County and now lives in Knightdale.

Lake Mattamuskeet, the state’s largest natural lake and Hyde County’s most prominent feature, bears an Algonquian name meaning “dry dust.” That seems counterintuitive until one learns that the lake wasn’t always there. Scientists theorize that a meteor strike or a fire caused the depression that then filled with rainwater.

Like many tribes in present-day eastern North Carolina, the Machapunga — also interchangeably referenced as the Mattamuskeet — spoke Algonquian before Europeans arrived.

Other Algonquian names — Roanoke, Hatteras, Croatan — remain sprinkled throughout the landscape. Algonquian-speaking tribes were the first encountered by the English who landed on their shores beginning in the 1580s; and they took the brunt of the resulting disease, war, murders over land and forced relocation.

“There was a high degree of linguistic and cultural uniformity throughout the area explored by the English at that time, although several major political divisions were present among the Indian inhabitants,” Garrow wrote.

But the most damaging interactions were not intertribal; they resulted from European intrusion.

“It is known that encroachment by white settlers on Indian lands was causing problems by 1700, and that those encroachments were largely responsible for increasing the hostility between Indians and whites,” he wrote.

The Tuscarora War, which lasted from 1711-1715, involved the Mattamuskeet, Bay River, Pamlico, Neuse, Tuscarora, Coree, Woccon and potentially other small coastal Algonquian groups against the Europeans.

“Several of the small coastal groups disappeared completely as a result of the war and the remainder were greatly reduced in population,” Garrow wrote, calling the war “a disaster” for the tribes.

Post-war, the Native inhabitants were relegated to a roughly 4-mile-square reservation by Lake Mattamuskeet. For various reasons, the tribe sold off portions of the reservation lands to whites beginning in 1731, and all of it completely by 1761.

Detailed records about the tribal members are difficult to find.

That is explained by considering who historically kept all official records.

“The Mattamuskeets and their descendants were not represented in the Hyde County Records during the period in which they owned little or nothing of value that was desirable to the whites,” Garrow stated. Tribal members never held public office and didn’t even appear on county tax lists.

Some Native Americans from Roanoke and Hatteras islands moved to the area in the mid-18th century, according to Garrow. Still, the tribe “declined in both population and cohesiveness” in the last half of the 18th century, he wrote. There was much documented intermarrying with whites and Blacks — even when it was illegal — and a trend of the tribal members’ loss of culture for many reasons that continued into the 19th century.

“The history of the Mattamuskeets and their descendants may be typical of small fragmented triracial groups in other areas of the eastern United States,” Garrow opined.

Garrow acknowledged his “debt of gratitude” to Napoleon Mackey, whom he interviewed in 1975: “His concern for and interest in the history of the Indians of Hyde County made many parts of this research more meaningful.”

Mackey named the Collins, Barber, Chance, Clayton and Bryant families as other area families also of at least partial Native American descent.

For his part, he “traces his Indian descent to his great-grandfather Benjamin Mackey, who was supposedly a ‘pure-blooded’ Indian,” Garrow wrote. “Benjamin Mackey was never apprenticed and was apparently able to go through a type of enculturation denied to many of his relatives.”

This was significant. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Mackey retained a sense of Native identity and was able to pass on at least some oral traditions of the tribe.

Apprenticeship for many

The apprenticeship policy in Hyde County from 1834-1865 effectively disintegrated the nuclear family structure and the cultural heritage of much of the tribe, Garrow found.

During this time, Native American children were placed in white households from as young as infanthood — and the majority by age 9 — until they reached age 21, to be taught a specific trade. There were no requirements for them to be taught to read or write, nor to be paid. Most boys were “apprenticed” to be farmers and most girls to become seamstresses or house servants.

Hyde County’s “Apprentice Bonds” records from 1771-1849 are included in “The Mattamuskeet Documents,” and children with the surnames of Mackey, Collins and Long Tom are well represented in that list.

“That policy may have been an attempt by white planters to neutralize the free nonwhite population,” Garrow wrote. “It is probable that well over half of the children of the free persons of color became apprentices during this time.”

The widespread apprenticeship policy meant there was “little opportunity for the older generation to pass on whatever elements remained of their Indian heritage,” he explained.

Beginning with the 1804 records, Garrow found that people with known Mattamuskeet tribal surnames were referred to as “free persons of color” instead of “Indians.” That social status, shared with free Blacks, was only slightly higher than that of the enslaved; they similarly did not own land.

From 1804-1834, only orphaned Native children were apprenticed, but that “changed dramatically” in the 1830s, three decades before the Civil War. The North Carolina General Assembly had stripped “free persons of color” of most of their rights by 1835, Garrow noted.

Dr. Lason Mackey-Hines, a distant relative of Brown’s who also traces her lineage to the Mattamuskeet Tribe and also is a journalist by trade, noted the huge consequences of apprenticeship.

“If you could pass for white, or if you could pass for Black, you’re going to go with one of those because you’d want to not give up all of your freedom,” Mackey-Hines said.

The decades of the apprenticeship policy left a continuing legacy of fear around tribal members asserting their Indigenous identities.

“I can understand why a lot of my family members wanted to move to New York or somewhere else, because of fear and not being able to really identify who you are,” she said. “Choose your safest route; don’t talk about it anymore. You forget it, let it go; don’t bring it up. There’s tons of books about Natives who chose to go one way or another in order to survive.”

Mackey-Hines grew up in Pennsylvania and now lives in Humble (pronounced “umble”), Texas. Like Brown, she knows she has Native ancestry on both sides of her family and traces one side to the Mackeys and Barbers who lived in Hyde County. She said her grandfather’s grandfather, Benjamin Mackey, was never apprenticed.

Her grandfather, James Mackey, showed her family photos when she was young. “You’re a Mackey. Know who you are. Know you’re a very important person; you come from the eastern North Carolina area,” she recalled him saying repeatedly.

He didn’t elaborate, but through hearing him talk about the family photos, “I started to slowly pick up on some things,” Mackey-Hines noted. “I used to laugh because … it seemed all the kids were nursery rhymes. I was like, ‘Whoah, didn’t anybody have a normal name?’”

Over time, she figured out those were Indigenous names. She heard stories of tobacco farmers and gardeners; her ancestors survived off the land.

Josephine Mackey, her great-great-aunt, was a well-known midwife and healer.

“She was very keen and knew a lot about herbs; she knew how to put some together to help whatever you were going through,” Mackey-Hines said. “A lot of that was passed down. My great-grandma started doing it and talking about it.”

Despite historical oppression, fear and movement, Native heritage remains strong.

“We’re alive, we’re well, we’re here,” Mackey-Hines said. “Our stories have passed down.”

Making connections

Brown said Mackey-Hines connected with her through a genealogy website, and they met in person around 2003 on the Outer Banks.

“My great-grandfather’s mother, Clarissa Mackey, was related to Lason’s great-grandfather; they were cousins, I believe,” Brown said. And, strangely, both their great-grandfathers had the same first and last names: Benjamin Mackey.

Brown and Mackey-Hines noted the difficulties inherent in researching their family lines. They must rely on oral tradition, Census records, court records and historical records written by traveling demographers or historians.

Census enumerators working in the area — generally white males — seemed to have identified people “solely based on skin color,” Brown said. “Just like any other category of people, skin tones can range from being very, very fair to very, very dark.”

Over a span of just a few decades, she found it common that the same Native individual would be alternatingly identified as M (“mulatto”), Black and white.

“Census data is very important, but it can also be tricky as well,” Brown said. “Sometimes it leaves you with questions: What was the enumerator seeing? What did he see during that time?”

“You have to rely on oral tradition, which is very, very integral to the Native American and African American experience, to be able to know (you are Native),” Brown said. “It’s really like putting together a puzzle … weaving things together.”

She’s still trying to trace exactly where in Africa her African American ancestors were from. But research on her family’s Native heritage consistently leads to Cape Hatteras and Lake Mattamuskeet.

Her mother, Ethel Mackey Brown, had family roots going back to present-day Dare County; some of her ancestors moved to Fairfield after a series of hurricanes and storms.

“She said that our family suffered lots of struggles and discrimination throughout their lives, but they were always viewed as free people,” Brown said. “And that conversation evolved out of the discussion about slavery in America.”

Civil rights

By the 1950s, Hyde County residents were mostly impoverished and were only officially referred to as Black or white. Native American wasn’t a category on the Census at the time.

The federal government, timber corporations and agribusinesses owned almost 90% of the county, and only two North Carolina counties — both in Appalachia — had higher poverty than Hyde, according to David S. Cecelski’s 1994 book, “Along Freedom Road.”

Only about a third of white families had access to hot running water and flushing toilets, according to the 1950 U.S. Census. No Black family had those luxuries; few had electric lighting or refrigerators; and many couldn’t even afford iceboxes, Cecelski noted.

“Hyde County’s white citizens had colluded for generations to thwart black aspirations for political and economic advancement,” he wrote.

Thus, Black residents “lived in ramshackle homes crowded onto the mosquito-ridden banks of drainage canals or blackwater creeks, often exactly where their great-grandparents had once lived in slave quarters or settled in the first years after the Civil War.”

Every aspect of life in Hyde County was defined by Jim Crow laws, as it was in the rest of the South. And as with the rest of the South, school desegregation, once mandated, was put off as long as possible.

Despite this bleak background, Black and Native American residents in Hyde County would manage to be strikingly successful in their protests to preserve their school heritage and leadership in a way few other Southern communities of color were.

Not only that, but their school boycott in the late 1960s drew national attention to the significant issues with how schools were being integrated.

Brown said she prefers the term “people of color” to acknowledge her family’s Native American ancestry as well as their African American heritage.

Brown’s grandfather, Golden Mackey, and mother, Ethel Mackey Brown, were involved in those school preservation efforts.

Next in the series: A civil rights success.