Coastal Review Online is featuring the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state’s coast as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.

Today I am at the archives and library of the Linnean Society in London, England. Founded in 1788, the Linnean Society is the oldest biological society in the world. I am only in London for a few days, but while I am here, I cannot possibly resist visiting some of the Society’s treasures, including a letter from 1759 that I have wanted to see most my life.

Supporter Spotlight

The Linnean Society sits in an old and revered square in Piccadilly Circus, just down the road from Buckingham Palace, where, as I write this, tremendous crowds are gathering to mourn the Sept. 8 passing of Queen Elizabeth II.

An English botanist, Sir James Edward Smith, was the Linnean Society’s founder. The Society’s first collections were those of Carl Linnaeus, the great Swedish botanist and physician who was the Society’s namesake. After Linnaeus’s death in 1778, Smith acquired his personal library and correspondence, as well as his specimen collection of plants, insects, shells and fish, and brought them to London.

They are still at the Linnean Society today. In fact, I’m sitting just across the room from a display case that features a doting fan letter that Jean-Jacque Rousseau sent Linnaeus in 1771.

One of the leading scientific figures of the Enlightenment, Linnaeus is best known for creating the taxonomic system for naming, defining and classifying organisms that is still used by scientists today.

Examples of Linnaeus’s system of taxonomy—called “binomial nomenclature”— include Homo sapiens (meaning “wise human” in Latin) for us human beings.

Supporter Spotlight

Or as a less aspirational example, one of my favorite plants back home on the North Carolina coast is Ilex vomitoria, commonly known as yaupon, a species of holly with lovely red berries. (Ilex for holly and vomitoria because the coastal Algonquins used as it as a ritual purgative).

The Linnean Society holds an even more important place in the history of science for another reason: this is where Charles Darwin first publicly presented his theory of evolution and natural selection.

On July 1, 1858, here in these rooms, Darwin gave the world a first look at the theory that he would elaborate more fully 15 months later, when he published “On the Origin of Species,” arguably the most important scientific work ever published.

As I write this, I am sitting next to a display case that includes a vasculum, a collecting box for plants, that Darwin used while serving as a naturalist on the voyage of the H.M.S. Beagle in 1831-36.

I find it just breathtaking to be here. It’s exciting and awe inspiring and frankly heartbreaking too, because of course I can’t forget how the scientific discoveries chronicled here went hand in hand with the spread of European colonialism and unprecedented environmental devastation.

In these old manuscripts and relics, we see scientists and explorers discovering and celebrating the glories of the world’s biodiversity. But it also feels a little strange, because I can tell that they did not yet know what we know: that it is all fragile and will only last if we make it last.

If I could, I would be here all week. I would browse the great British naturalist and explorer Alfred Russell Wallace’s journals. I would also look at the Society’s rare copy of Elizabeth Blackwell’s “A Curious Herbal,” a gorgeous reference book of medicinal plants that was published here in London in weekly installments between 1737 and 1739.

Maybe I would even take a look at the seashells that were collected on James Cook’s epic voyage to the South Pacific in 1771.

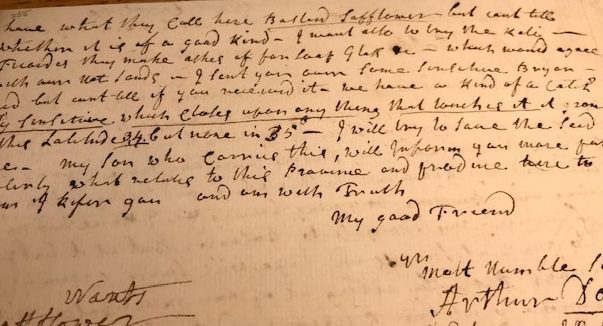

But I have time to do only one thing today, and it’s why I am here. I am holding in my hand a letter from the North Carolina coast that colonial governor Arthur Dobbs wrote on April 2, 1759.

He wrote the letter to an English botanist, Peter Collinson. In that letter, he told Collinson about a tiny but amazing insectivorous plant that was only found in the moist longleaf pine savannahs and pocosin swamplands within a 90-mile radius of present-day Wilmington, North Carolina.

The description is brief, but unmistakable: “We have a kind of Catch Fly Sensitive which closes upon anything that touches it. It grows in Latitude 34 but not in 35. I will try to save the seed here.”

The plant of course was the incredibly beautiful, utterly fascinating species now called the Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula).

Few of God’s creations symbolize the place I call home more. Few symbolize the beauty, uniqueness and fragility of our coastal wetlands more either. And, according to historians of science, this letter is the oldest and first known written record of the Venus flytrap in the history of the world.