HATTERAS — As it turns out, long-sought flexibility in maintenance of essential Hatteras Inlet navigation channels didn’t take an act of Congress. It boiled down to a much simpler concept: go-with-the-flow realignment.

But with the finalized expanded authorization to dredge Rollinson Channel, it may seem like a Christmas miracle for islanders now relieved of navigating a labyrinth of regulatory hurdles to address shoaled channels.

Supporter Spotlight

For Steve “Creature” Coulter, a Hatteras charter boat captain and chair of the Dare County Waterways Commission, the new realignment, which he said Dec. 2 was a “done deal,” is delayed validation of his initial assessment.

In 2013, as Coulter recalled in a recent interview with Coastal Review, when the waterway’s “short route” between Hatteras and Ocracoke islands was deemed too dangerously shoaled to dredge, he called the office of the late 3rd District Rep. Walter Jones and suggested, essentially, that the law allowed channel dredging to follow best water.

But at the time, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the agency charged with maintenance of Rollinson Channel, said that an act of Congress would be required to change the channel’s authorized metes and bounds.

“If we could do just what we wanted to do, I’d have had it done nine years ago,” Coulter said, recounting what he half-jokingly told Josh Bowlen, who had served as Jones’ legislative director, and later, chief of staff.

After Jones’ death in 2019, Bowlen has served as legislative assistant for Sen. Richard Burr, R-N.C., who will retire in January.

Supporter Spotlight

Although it’s not clear when the Corps adopted its different stance, its authority to follow the deepest natural water, or best water, in the Rollinson Channel Navigation Project was explained in the environmental assessment and finding of no significant impact, or FONSI, that was signed Nov. 30 by Robert M. Burnham, acting district commander for Corps’ Wilmington District.

The realignment of a portion of the project’s Hatteras to Hatteras Inlet Channel that follows deep water, the document said, was “due to the changes in shoaling patterns” caused by the dynamic inlet conditions.

“The project’s authorization does not specify the precise location of the Hatteras to Hatteras Inlet Channel, and therefore the location may be altered if found to be justified,” the document said, citing a regulation that allowed modifications.

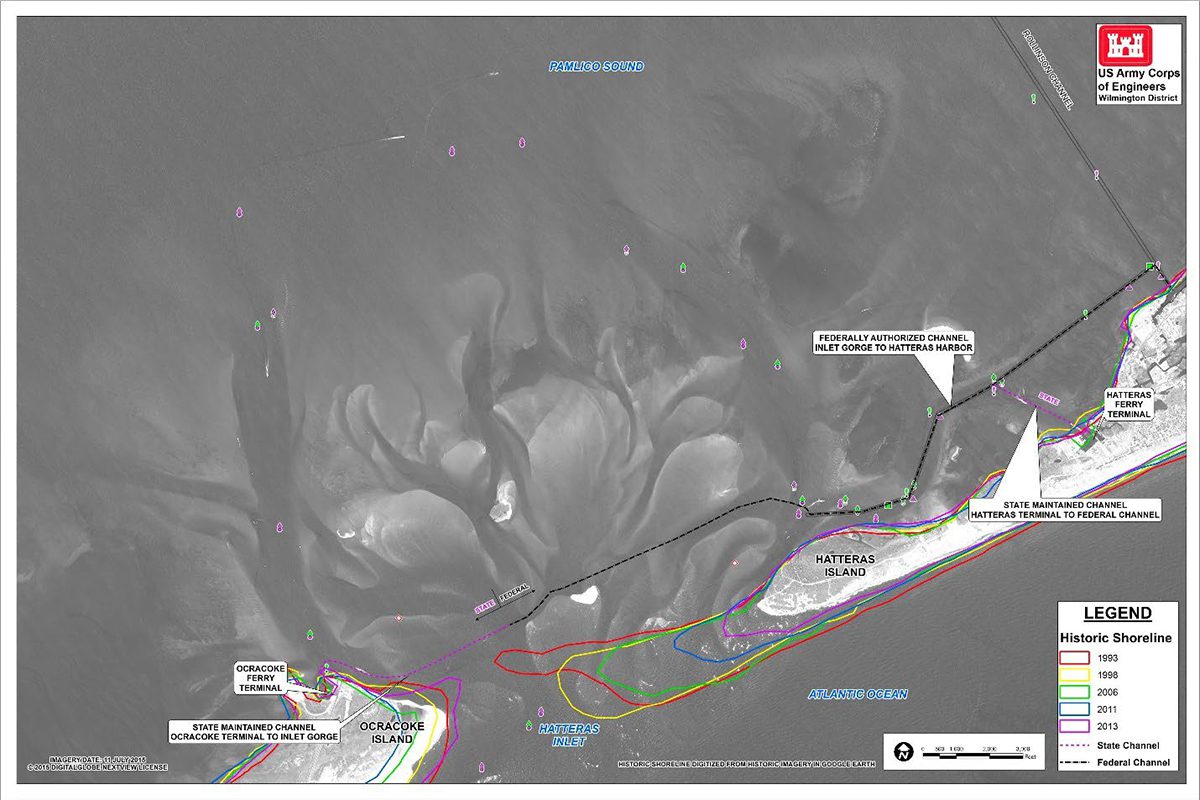

The channel was originally authorized in 1962 under the River and Harbor Acts and included a 100-foot-wide, 12-foot-deep fixed channel extending through Rollinson Channel from Hatteras Harbor to Pamlico Sound, and a 100-foot-wide, 10-foot-deep channel from Rollinson Channel to the Hatteras Inlet gorge, with part of the channel being fixed and part following best water.

Somehow, what Coulter and other mariners considered common sense broke through to the surface.

“Having a channel that follows natural deep water to the extent practicable,” according to the environmental assessment, “given the natural dynamic nature of sediment movement, will allow for a safer, more reliable channel, reduced dredging effort, and an associated reduction in maintenance dredging costs, as well as having the least impact to the environment.”

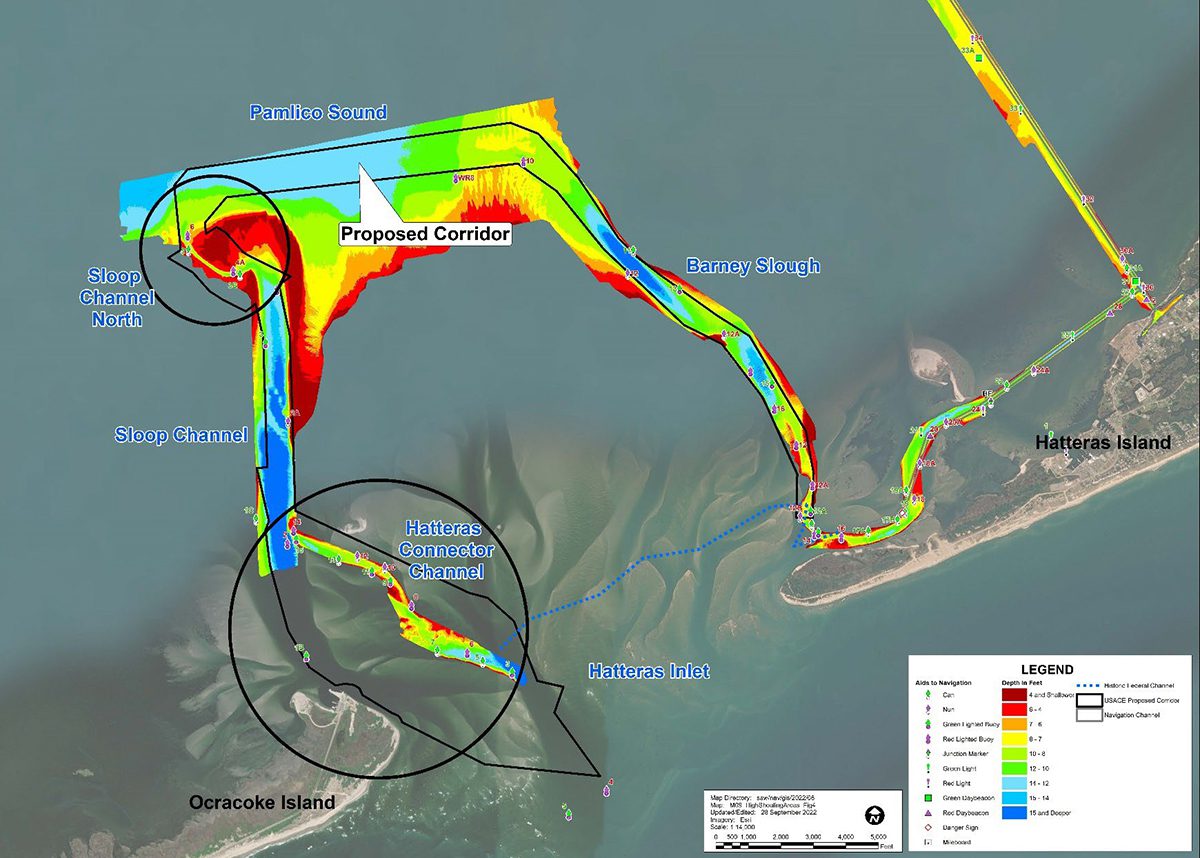

Of the three actions proposed, the preferred alternative that was approved chose to abandon the “historic direct route” to the inlet gorge and to reroute the channel to follow best water along what is known as the “horseshoe route.”

“This is the only way for (the Corps) to economically maintain access to the gorge at Hatteras Inlet and will allow transportation of passengers, goods, and services to continue from the mainland, as well as allowing safe access to open ocean waters,” according to the document.

Not only will the dredging be able to be more flexible and timelier, the realignment also frees up use of federal funds for work within the project.

Work in the horseshoe will be allowed between Oct. 1 and March 31. Also, Sloop Channel North and Hatteras Connector Channel can now be maintained any time of the year.

Decades before the short route became impassable and impossible to dredge, the inlet was stable and rarely had navigational difficulties. After 1993, when the inlet was 0.35 miles wide, the southwest end of Hatteras Island began eroding, likely spurred by the effects that year of the “Storm of the Century” and Hurricane Emily.

As detailed in the environmental assessment, sand from the eroding land over the years, as well as what drifted through the widening opening to the ocean, resulted in more shoaling. By 2019, about 315 acres from the tip of Hatteras was gone, and the inlet had widened to 1.7 miles. At the same time, about 130 miles of shoreline was lost from the eastern end of Ocracoke Island. Today, the inlet is over 2 miles wide.

As navigation through Hatteras Inlet became more difficult, and the ferry route between Hatteras and Ocracoke islands switched to the longer horseshoe route, the commercial and charter fishing fleet, recreational boaters and fishers and the Coast Guard, also had to adapt their routes to reach Ocracoke and the ocean, depending on shoaling.

It soon became evident that dredging would be needed beyond the authorized Rollinson project the Corps had been maintaining. Problems developed in a confusing number of channels, or portions of them, some with evolving names. The South Ferry Channel — for a time a “no-man’s land” that no one had permission to maintain — became too shoaled to dredge and was replaced by the nearby Connector Channel.

But the piecemeal of jurisdictions, funding pots and government administrators — local, state, federal — involved in addressing problematic areas often resulted in time-consuming permit applications and costly delays.

Agreements had to be made among the county, the state and the Corps for certain work to be done, also not a quick process. Often, certain dredges were needed for certain conditions, but they weren’t available. Sometimes dredges were called away for a more pressing need, or broke down mid-project. A shared funding pot would be depleted by a more urgent project, such as the ferry route, leaving little or nothing for another needy channel. More than once, dredging projects would be undone by storms not long after they were completed.

For the last five or so years, members of the Waterways Commission were often left frustrated by numerous twists of fate and bureaucratic complications. Confronted repeatedly by the Corps inability to clear bits of shoaled channel outside the rigid authorized Rollinson parameters, the commissioners’ running theme through the years was the need for flexibility.

With the new flexibility, a Corps dredge on its way elsewhere would be able to do a little clean up where needed in Hatteras Inlet.

“If there’s money in the budget for Rollinson Channel, they can just stop by and do the work,” Coulter said.

Finally, in a big way, the realignment, while not a panacea, fills in gaps and removes one of the more persistent blockades to addressing the unpredictable nature of shoaling, while offering responsive dredging that can save time and money.

That means the Connector Channel, Crossover Channel, Sloop Channel, Hatteras Ferry Connecting Channel and Barney Slough, all of which may have had different names or versions that were maintained in different ways, will now be part of the expanded Rollinson project, explained Dare County Grants and Waterways Administrator Barton Grover.

It also puts Hatteras Inlet on par with Oregon Inlet in funding projects. For instance, the Corps just did $400,000 worth of work in the last three months in Oregon Inlet, and it cost Dare County “not one cent,” he said.

“In a nutshell, it’s a positive,” Grover said about the Hatteras realignment. “We now have access to federal dollars for the entire inlet.”

Also, there will be an additional area provided to dispose of dredged material, an important requirement for every dredge project.

Last year, he said, Dare dedicated $250,000 for Hatteras Inlet dredging, with a 75% match in state dollars, paid out of the state Shallow Draft Navigation Channel Dredging and Aquatic Weed Fund.

Dare also budgeted $800,000 for its new hopper dredge, the Miss Katie, which will often be used to supplement Corps work. In addition, the Corps received $1.43 million for Rollinson Channel from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and $580,000 remained as of mid-November.

Since so much of the dredging situation has changed, Grover said, it will take time to gauge the impact on the maintenance and emergency work and the budgets. The reality, he added, is that even though the Corps now has the authority to dredge much more of Hatteras Inlet, it doesn’t mean it will have the funding or the available equipment.

If push comes to shove, he said, the county and state may have to supplement the cost of projects.

“I believe we’ll have a better sense in September of what it costs to maintain the ferry channel,” Grover said. “It’s a brand-new thing, not only with the federal channel, but also with us having Miss Katie.”