This story has been updated to clarify details on testing protocols.

DUCK — It was flashback to high school chemistry class for some, but Duck residents were up to the challenge last week at an information session about a carbon capture demonstration project proposed off their beach.

Supporter Spotlight

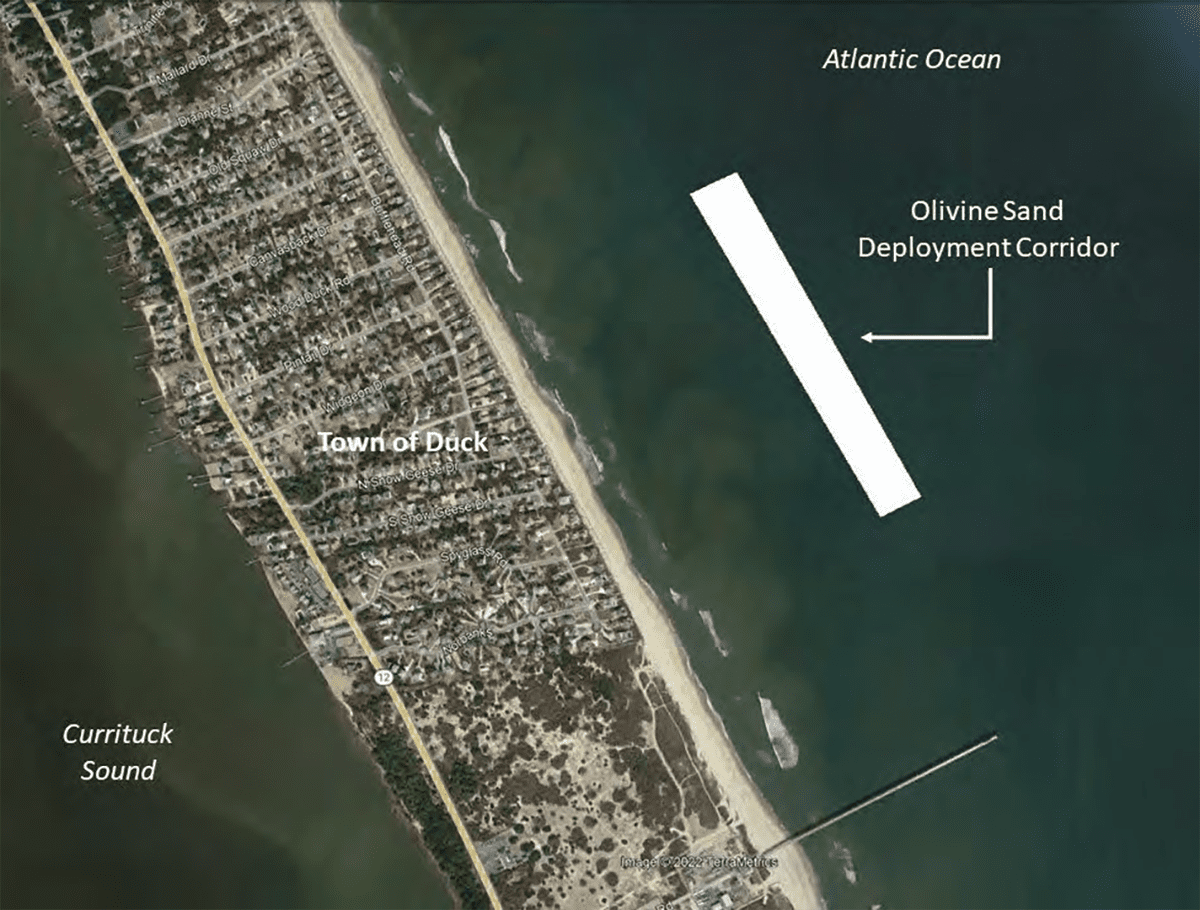

Vesta North Carolina is seeking a permit to place about 20,000 cubic yards of ground olivine in the nearshore waters 1,500 feet from the shoreline of this northern Outer Banks town.

The intention is to study on a small scale the ability of the material to mitigate the impacts of climate change. But residents wondered about unknown risks inherent in a test project, and if their resort community might be stuck with the consequences if it went awry.

Other projects the company has conducted using olivine are in Massachusetts and New York, although neither has been done in the open ocean.

“There’s 330 miles approximately of shoreline in North Carolina and there’s over 120 miles of them that have no population on them,” one Duck resident commented. “Why does it have to go here?”

One big reason is the town’s resident coastal science behemoth, the Army Engineer Research and Development Center’s Field Research Facility. That’s what Grace Andrews, Vesta’s head of science, told a full room of attendees at the Nov. 17 meeting. Informally known as the Duck Pier, the 45-year-old oceanfront site is renowned worldwide for decades of innovative research and volumes of data on coastal processes.

Supporter Spotlight

The Corps’ Engineering with Nature, or EWN, program is partially funding the Vesta project, and scientists at the pier are collaborating on the project with Vesta.

“You have one of the best-studied beaches of anywhere in the United States,” Andrews said. “The sheer knowledge here makes this location invaluable in terms of ensuring that we can do world-class, rigorous science. It’s unparalleled, and it’s frankly unequaled anywhere else.”

Olivine, named for its green hue, is a magnesium silicate mineral that is similar to quartz, the main ingredient of the sand on Outer Banks beaches. But it has an important difference: Olivine can capture carbon dioxide, the main greenhouse gas blamed for global warming.

“It is an incredibly common mineral,” Andrews said. An inert rock, olivine can be found all over the world, including in large quantities in western North Carolina, and it can be mined and milled to specific grain size. But the only active mining currently in the U.S. is on the West Coast. “Why do we care about all this? It’s because it has a special property that removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere when it comes into contact with the water.”

Andrews, who has a doctorate in Earth science from Northwestern University, explained that olivine’s unique quality is part of a natural process known as mineral weathering that happens whenever water meets rock. But not all minerals remove carbon, she said, as olivine does.

“When it dissolves, when it goes through this weathering process, it removes about one ton of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere per cubic yard of olivine,” she said. “And it permanently stores it in the ocean as a form of dissolved carbon called alkalinity.”

The goal of the test project, she said, is to quantify carbon removal efficiency and confirm prior academic research that it is safe and meets Environmental Protection Agency-established protocols in tests conducted by a National Environmental Laboratory Accreditation Program-certified laboratory.

Displaying chemical formulas on the screen during her slide presentation, Andrews provided a mini-lesson in the chemical processes involved: Carbon dioxide, or CO2, plus water, or H20, equals the acid H2CO3. It happens every time it rains, she explained.

“But when you combine that with the olivine, what you do is, you drive a mineral weathering reaction that takes that carbon dioxide and turns it into dissolved carbon. So, you’ve now moved that carbon dioxide from carbon dioxide in the atmosphere into this carbonic acid and into a dissolved carbon called alkalinity. And it’s that alkalinity that’s good for the ocean. That’s what offsets ocean acidification.”

Although the concept, broadly known in the scientific and academic circles as ocean alkalinity enhancement strategies, has been studied for more than a decade, she said, Vesta’s plan is just one in a range of technologies being proposed to field test the concept. And she noted that a National Academies of Science, Engineering and Mathematics report published this year emphasized the need for small-scale research and development projects in the ocean such as Vesta’s pilot demonstration.

Vesta, based in California, is a hybrid, public benefit corporation and nonprofit, allowing it to do its work without worrying about profit margins, while also able to accept contributions from donors.

The company had initially approached Duck last year with a proposal to piggyback its pilot project on the town’s planned beach nourishment, about which it provided a presentation at the June 16, 2021, town council meeting. But ultimately, the timeline for both projects did not work, and Vesta scaled the test research back to a much smaller quantity of olivine that would be kept off the beach by the natural nearshore sediment transport system. After updating the town at its council retreat in February, Vesta submitted applications to the Corps and the state. Those applications were pending approval at the time this story was published.

The material is expected to be shipped from an unspecified mine in Norway and deposited under 25 feet of water off Duck. Although olivine does contain trace minerals such as nickel and chrome, Andrews said, any leaching would occur over decades. Coupled with the volume of water moving around the material, she added, any release signal would be immeasurable.

According to the website for Sibelco, which operates the world’s largest commercial olivine mine deposit in Aheim on the west coast of Norway, olivine is the primary component of the Earth’s upper mantle. It also has been found in meteorites, on the moon and on Mars.

Thanks to olivine’s thermal and refractory properties and high melting point, the site said, the mineral is commonly used in metallurgy industries. Olivine is also the fastest weathering mineral, which lends it the ability to efficiently sequester carbon. It is also useful for high-density ballasting, such as for wind turbines, and for thermal heat storage.

“Looking ahead, the recent development of new environmental applications means that Aheim is today supporting a greener future with innovative solutions for carbon sequestration, renewable energy, water treatment and heat storage,” according to the website.

Andrews assured residents that the test project includes a monitoring program with divers and research buoys. She also promised that not only would the olivine not come near the shoreline, and even if it did it would not turn the beach green – a concern one resident had expressed. As a sample she brought to the meeting showed, the small volume of olivine compared with beach sand would completely dilute any green tinge.

The town would have no involvement or authority over the project, said Duck Town Manager Drew Havens.

Despite some skepticism about the proposed project expressed in numerous questions from the audience at the recent information session, Havens said that he had heard mostly openness to the project from residents and the town council, which agreed in February to send a letter of support to the Corps. Only one person at the Nov. 17 meeting questioned the validity of climate change.

“It’s great to see people engaged and involved like that,” he said.

Havens said that some folks may have felt blindsided because there hasn’t been much public discussion about the pilot project since it was downsized, although the public meetings have been available to view online. When stakeholder property owners were recently notified by Vesta about the informational meeting, he said, it renewed interest in the project.

“You have people who are very, very passionate about their community and their home,” Havens told Coastal Review. “Having those different conversations doesn’t mean anything bad. We have a community that’s very inquisitive.”

Both the town and Vesta said that efforts will be stepped up to provide more transparency and wider availability of current information about the project.

After listening again to Andrews’ presentation, Havens said that he is even more comfortable that the project is not risky for the town. He also said he appreciates that the Duck Pier is supporting the project as an innovative approach to mitigate carbon emissions.

“I understand people’s unease,” he said. “I do have a certain amount of trust in the scientific rigor, not only with Vesta, but with our regulators.”