Editor’s note: Historian and author Kevin Duffus is set to present a newly produced lecture, “The Battle at Ocracoke — What Really Happened,” at this year’s Blackbeard’s Pirate Jamboree Oct. 28-29 on Ocracoke Island. For more details visit the Facebook event.

OCRACOKE — It began within minutes after the notorious pirate Blackbeard was killed in the Battle at Ocracoke on Saturday morning, Nov. 22, 1718.

Supporter Spotlight

As soon as the wounded were attended to and the surviving pirates were placed under guard, the hunt was on, led by Royal Navy Lieutenant Robert Maynard. The first place they searched was Blackbeard’s cabin in the roundhouse of his 65-foot-long Jamaica-rigged sloop, Adventure. Surely the world’s best-known and most-feared pirate captain kept a chest of Spanish gold, silver and jewels hidden beneath his bunk, just for his walkin’ around money.

Rarely mentioned in the many books, articles and other accounts of the famous battle is that Maynard and the other volunteer sailors from the British king’s ships stationed in Virginia were persuaded to accept the potentially deadly assignment of apprehending or killing the North Carolina pirates by the prospect of acquiring pirate treasure. It could be said that the 60 men aboard the two, small, rented sloops under Maynard’s command were little more than pirates themselves.

Two weeks after the smoke cleared from the battle, Maynard and his men were still hoping to find a treasure on Ocracoke Island that would make them all rich. They were disappointed. In addition to casks of sugar, cocoa, indigo dye and a few bales of cotton, only a small amount of what is called gold dust, small nuggets of gold, were recovered from the pirates’ possessions.

Maynard’s stay at Ocracoke may have been when an enduring Blackbeard myth was born. While nine captive pirates were held in the lower deck of the Adventure while anchored in the yet-to-be-named Teach’s Hole Channel, a guard may have asked them, So, where did the boss hide his treasure? Funny you should ask, a pirate replied, we posed that question to him just last night.

The published version of the interrogation in a 1724 book, ”A General History of Pirates,” goes like this: “… one of his Men asked him, in Case any thing should happen to him in the Engagement with the Sloops, whether his Wife knew where he had buried his Money? He answered, That no Body but himself and the Devil, knew where it was, and the longest Liver should take it all.”

Supporter Spotlight

Among the many dubious aspects of the preceding quote, my research has proven that Blackbeard and his men had no idea on the night before the battle that they were under any threat at all. Having arrived from the inland waters of the colony and anchored alongside Beacon Island 3 miles away from the pirates’ moorings near today’s Springer’s Point, Maynard’s sloops had all the appearances of typical merchant vessels preparing to put to sea.

Nevertheless, ever since, writers and historians have assumed that because the quote was in print – like so many other popular but improbable Blackbeard legends – it must have been true.

At the end of the two weeks at Ocracoke, Maynard sailed Blackbeard’s Adventure across Pamlico Sound and up to Bath, but not with the pirate’s head hanging under the bowsprit as is so often told – it was too valuable, worth a bounty of 100 pounds sterling back in Virginia. In Maynard’s wake, however, has streamed, like the gold of marine phosphorescence, the hopes of the credulous that Blackbeard’s lost treasure might still be found.

Edward Thatch, aka Blackbeard, was far from a successful, wealthy pirate. When the value of the commodities recovered from the pirates’ possessions at Ocracoke were tallied up and sold at auction in Virginia, the proceeds amounted to 2,500 pounds sterling, not a treasure commensurate with the notorious pirate’s reputation, then or now.

Compare Blackbeard’s final estate to Capt. William Kidd’s £14,000 worth of gold, silver, and jewels; or the East Indian pirate Henry Every’s much more impressive £350,000 haul; or Sam Bellamy’s estimated plunder of as much as a million pounds sterling. But that all ranks well below Sir Francis Drake’s massive piratical treasure of £1.5 million valued in 1582. Yes, Drake was the greatest pirate of them all.

But historical facts be damned, the world’s best-known pirate had to have had a massive treasure hidden somewhere, right? Seeking their own treasure of sorts in the form of royalties or writing fees, authors, journalists, and artists have perpetuated the notion of lost pirate treasure and enticed all sorts of believers to search for it.

Robert Louis Stevenson really sparked the public’s imagination of instant wealth with his book, “Treasure Island,” first published as a weekly serial in a children’s magazine in 1881, and then as a more popular book in 1883. As many as five films have since been made based on the book.

The 19th century Delaware artist and writer Howard Pyle helped to paint the public’s perception of pirates and Blackbeard in particular with his illustrations like the one titled, “Blackbeard Buries His Treasure” that was published in Harper’s Magazine in 1887. It was also Pyle who conceived our modern ideas of pirate dress favored by Hollywood and pirate festival reenactors, fanciful things like sashes, bandanas, earrings and knee-high riding boots, all extremely impractical for men aboard a working vessel.

Most illustrations, such as those of Pyle, often depict sea rovers gathered around a hole in the sand on some unknown shore, and a sea chest nearby wrapped in chains and ready to be lowered into the ground. No one seems to question the practicalities of such a surreptitious mission. Even a small sea chest filled with gold, let’s say 2 feet by 2 feet by 2 feet, or 8 cubic feet, would weigh nearly 5,000 pounds. That’s a lot of weight for two pirates to lug about a sandy beach. No wonder the National Park Service claims that Blackbeard possessed “inhuman strength.”

The antiquarian writer John F. Watson in his 1830 book, ”Annals of Philadelphia, and Pennsylvania,” firmly planted the idea that pirates like Blackbeard provided security at the site of their hidden plunder by burying atop their treasure chests the gruesome remains of a prisoner or crew member who was chosen by lot to be sacrificed – murdered, to be precise – and left behind to rot, and to discourage would-be treasure seekers. “Hence it was not rare to hear of persons having seen a spooke or ghost, or of having dreamed of it a plurality of times, which became a strong incentive to dig there.”

The 1920s were heydays for promoters of pirate treasure with both the New York Times and the Raleigh News & Observer spinning tantalizing tales of Blackbeard’s vast fortune being found.

According to the Times, Miss Florence E. Steward of Burlington, New Jersey, wanted to sell her house in 1926 near the Delaware River but according to family lore the old walnut tree in front, known as the “pirate tree,” was where Blackbeard had buried his treasure many years before. She didn’t want the treasure to be conveyed to the new owners so she hired some excavators to dig it up. For unspecified reasons, Miss Steward wasn’t present when the digging commenced. At the end of the day the excavators were gone but there was a large hole in the ground. The Times reported that the contractors had been observed by neighbors prying “a large, heavy object” from the earth and taking it with them when they departed. They were never seen again.

Three years after Miss Steward’s walnut tree misadventure, Ben Dixon MacNeil, a correspondent for the Raleigh News & Observer, and later author of the much-beloved book ”The Hatterasman,” must have decided that Blackbeard’s home state of North Carolina would not be upstaged by New Jersey or the New York Times. MacNeil wrote a story for the Feb. 3, 1929, Sunday edition with a headline that was simultaneously buoyant and deflating: “Blackbeard’s Buried Treasure Found at Last; But Mystery of Pirate Gold Not Yet Solved.”

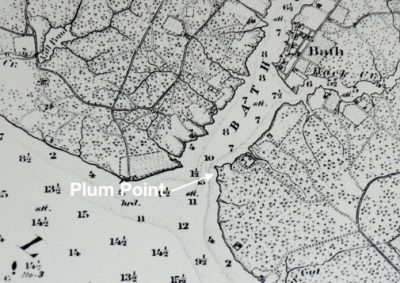

In MacNeil’s colorful two-page piece, he reported how, two days before Christmas in 1928, three men, believed to be duck hunters despite the fact that there were no eyewitnesses, visited by water Plum Point on Bath Creek in Beaufort County and found Blackbeard’s secret treasure vault, dug up a heavy chest, dragged it back to their boat and sailed away never to be seen again. Remember, there was no one who observed this, yet MacNeil reported it as fact. (Fictional news has been around a long time.)

Legend says that Plum Point had long been the treasure hunter’s favored location of Blackbeard’s ill gotten gains. “For two hundred years,” MacNeil wrote, “the earth had been troubled by the digging of those who had been shown in dreams where the chest was hidden.”

We might speculate that the News & Observer journalist had been influenced by Watson’s ”Annals of Philadelphia” in which the author described dreams leading treasure hunters to the “X” that marked the spot. Ironically, previous dreamers and diggers had missed the location of the secret vault near Bath by just 3 feet, or so the story goes.

According to MacNeil: “… the next day, or the next — the stories are in some conflict here — other hunters making their way through the thick undergrowth that covers the Point, came upon the broken brick vault” out of which had been removed a “mysterious chest containing, according to legend, uncounted pieces of Spanish gold.” (It is worth noting that there is no record that Blackbeard ever robbed a Spanish vessel in his documented 23-month career as a pirate.)

The vault, 18 inches wide and 3 feet long, had been buried 8 feet under the sand in an area so pockmarked with craters from previous treasure seekers that the landscape looked like the far side of the moon. Suspicious markings in the original mortar of the brick vault, and some accumulation of rust, led the other hunters to surmise that an iron-clasped wooden chest once resided inside the vault. That tidbit leads one to wonder if the “other hunters” had been archaeologists.

Nevertheless, Blackbeard’s brick vault has neither been authenticated or even found again. The foundation ruins of a small 19th century house near Plum Point, however, were examined by the late archaeologist Stanley South in the 1960s.

MacNeil concluded his article by writing that Blackbeard must have been an exceptionally wealthy pirate, who buried his Spanish gold beneath the sand of numerous eastern North Carolina locations, “because otherwise he would have not been worth bothering the British navy, and successful pirates have chests of gold buried about in places. And where else should he bury the gold except in his own backyard.”

Despite the newspaperman’s reasoning that Blackbeard lived at Plum Point or buried his treasure in his backyard, property records and deeds in the Beaufort County courthouse affirm that Edward Thatch or Teach, or anyone else for that matter, did not live on that prominent point of land at the mouth of Bath Creek in 1718.

Bath’s Plum Point may be among the best known and most “earth-troubled” mythical locations of Blackbeard’s lost treasure but there are many more. There are those who believed the pirate buried his money at New Hampshire’s Isle of Shoals, others who think it’s somewhere on the subtly named Blackbeard Island off the coast of Georgia, or at the base of any number of trees along the Atlantic coast. Have you ever tried to dig a hole at the base of a tree?

There is no doubt that Robert Louis Stevenson and Howard Pyle have launched the treasure hunting hobbies of many wishful Americans, some of whom, to this day, hope that Blackbeard’s treasure may yet be found.

So here’s a tip from someone who has spent decades researching the world’s best-known pirate.

If you wish to seek Blackbeard’s treasure, you might search the bank accounts of publishing companies, Hollywood studios, cable channel networks, museum stores, amusement parks, restaurants, and the importers of plastic pirate paraphernalia from Far East manufacturers. It’s there that “X” marks the spot, it’s there where the real pirate treasure can be found.