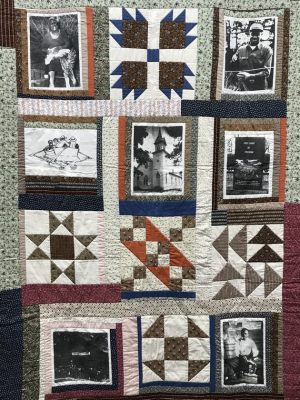

Legend says secret messages like those sewn into a commemorative quilt recently donated to the National Park Service helped guide runaway enslaved people on the road to freedom in the 1860s.

Crafted by a group of residents and donated by the family of the late Dellerva Collins, who served more than 26 years as a Manteo town commissioner, the 15-panel quilt and will be on display at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site visitor center in Manteo Sunday through June 30.

Supporter Spotlight

Collins is the mother of current town commissioner Darrell Collins, who retired after 40 years with the National Park Service. He spent most of his time in the division of interpretation and education as historian at the Wright Brothers National Memorial. His great-grandparents where members of the Black Freedmen Colony that settled on Roanoke Island in 1862 during the Civil War, according to the First Flight Foundation.

“The quilt represents a remarkable piece of history that everyone should see,” said Jami Lanier, cultural resource manager for Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, Cape Hatteras National Seashore and Wright Brothers National Memorial, in a statement. “It’s amazing how, despite the challenges, legends say enslaved African and African American people learned to improvise, communicating coded messages on what path to take and pitfalls to avoid as they began their journey to freedom.”

The panels are a mixture of traditional quilt patterns that have been said to highlight escape directions and advice as well as representations of people and milestones on the freedom trail, including a drawing by Glenn Eure, depicting runaway enslaved people arriving by boat to join the Freedmen’s Colony on Roanoke Island.

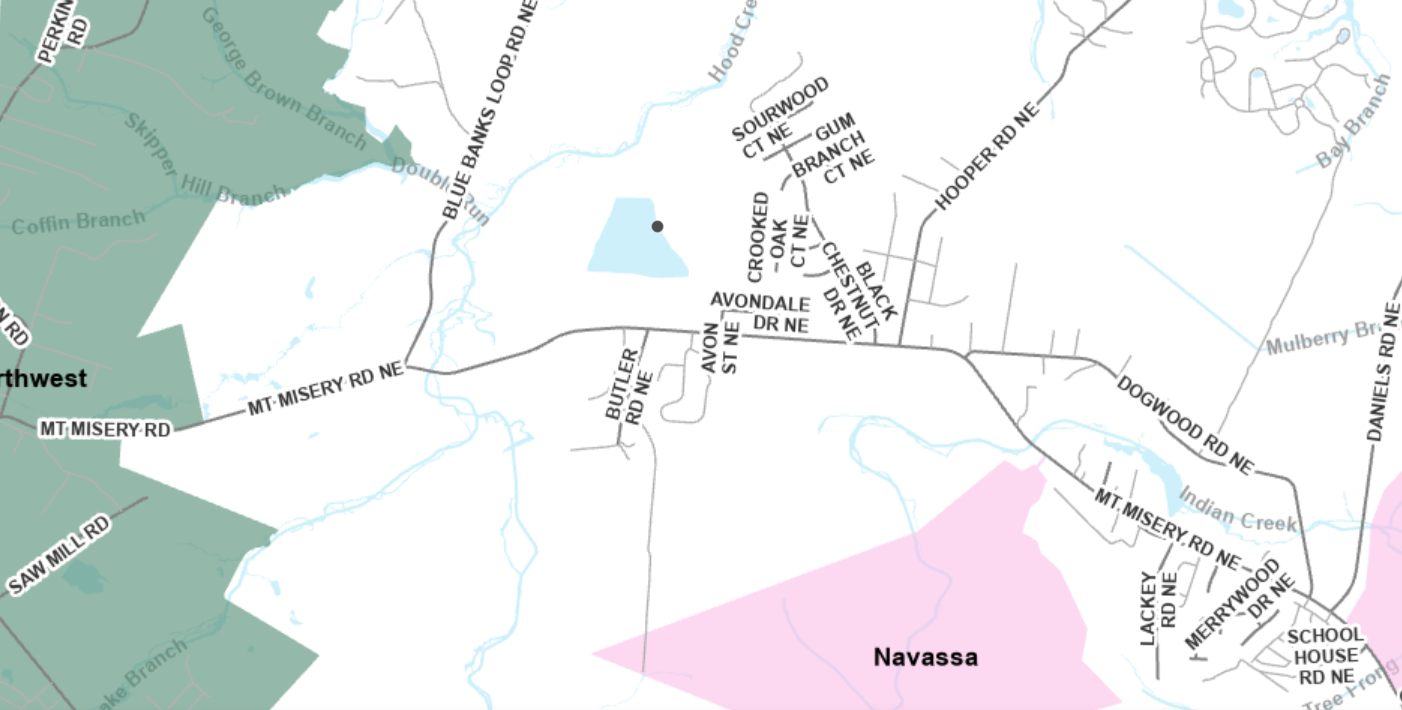

The community, established during the American Civil War, included schools, homes and a church and eventually sheltered more than 3,500 residents. The colony is the subject of the First Light of Freedom Monument on the grounds of Fort Raleigh National Historic Site.

“A number of Freedmen’s Colony descendants participated in the quilt project,” said Lanier, “and I think that personal connection adds a depth of meaning to the exhibit and the conversation on this important topic.”