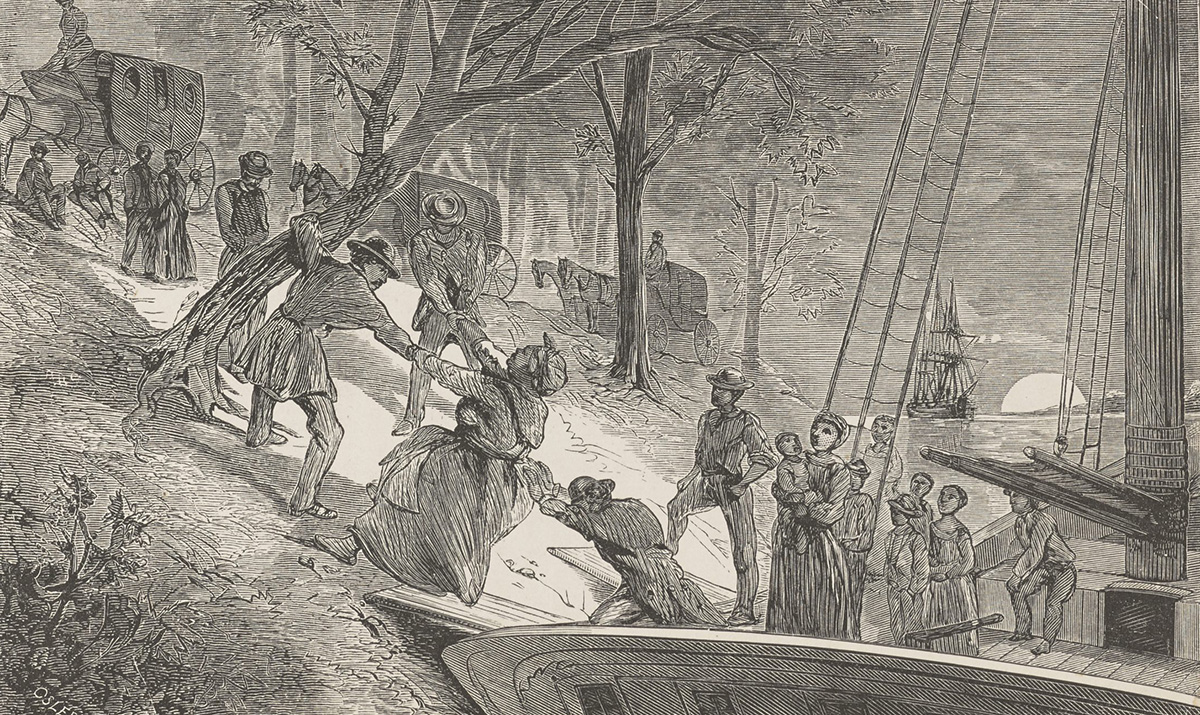

NEW BERN — A lesser-known story of the Underground Railroad is beginning to become clearer some 160 years after the Civil War began. Increasingly historians are viewing the waterways of the South as perhaps the most important component of that journey to freedom as enslaved people fled their bondage.

Although in the past much of the story of the Underground Railroad has emphasized terrestrial escape, Pathway to Freedom: The Underground Railroad in North Carolina Symposium held Saturday at Tryon Palace in New Bern, refocused that attention on escape by water.

Supporter Spotlight

Keynote speaker Dr. Timothy Walker, professor of history at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, framed the discussion, giving substance to the idea that the ports of Southern towns and cities were significant players in the quest for freedom.

“The overwhelming majority of attention on the Underground Railroad story up to this point, has been focused mainly on terrestrial escapes, and that’s extremely important,” Walker said. “But it’s only half the story.” He added that there’s a need to “shift our approach to the Underground Railroad, and change the way we think about it. The sea is a major central component of that Underground Railroad story.”

He pointed out that by a considerable margin the documented escapes using terrestrial routes of the Underground Railroad were from slaveholding states that bordered free states and very rarely came from the Deep South. And, he noted, there were practical reasons for that.

“Escaping over land to a territory that was unknown to people and the logistics of organizing food and shelter, traveling at night in an area that was essentially hostile territory, where there were organized slave patrols to pick you up, it was very, very difficult to do that successfully over a long distance,” he said. “The great majority of overland escapes that are documented as successful began within just a few days walk of the Ohio River and other places in Maryland, western Virginia, northern Virginia and eastern Missouri.”

For Walker, whose research includes maritime history and the slave trade of the Atlantic and Indian oceans, there was a practical reason why so little emphasis has been placed on the seaboard of the Southeastern states and the Underground Railroad.

Supporter Spotlight

“Historians have tended to look at the overland routes,” he said, “because many historians don’t have a lot of training in maritime records and documentation. They don’t come into the profession with an understanding of how and where those maritime documents can be found and how to analyze them and what they mean.”

There are also other reasons why the documentation of Underground Railroad escapes are often difficult to find.

“We’re talking about activity that was illegal, for which there were very serious repercussions,” Walker said. “So it’s illegal activity, and it was clandestine.”

He said the lack of documentation has made the job of historians more difficult. “They were doing this in ways that they didn’t want anyone to know about and they tried not to leave records.”

But if direct records of escape do not exist, circumstantial evidence abounds that points to water routes as significant pathways to freedom.

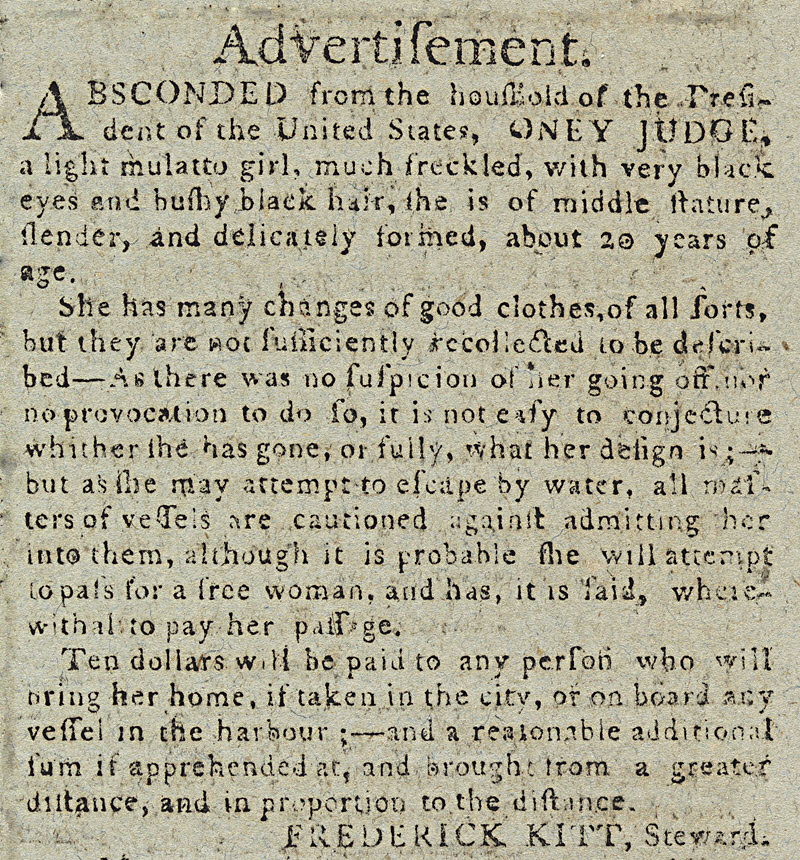

One of the best resources for historians trying to understand how enslaved people fled their situation is in the newspaper advertisements owners placed in hopes of recapturing the humans who were their property.

“There are approximately 200,000 runaway slave advertisements that are available in archives from North American newspapers. Beginning in the middle of the 1700s, 18th century, right up until the time of the Civil War,” he said.

Ads like these placed by President George Washington are among the documentation of his status as slaveholder.

“Absconded from the household of the President of the United States, Oney Judge, a light mulatto, much freckled with very black eyes …” read the 1796 advertisement, which went on to suggest that “she may attempt to escape by water.”

Oney Judge, who lived from 1773 until 1848, did, in fact, escape by water, probably sailing directly to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, after being hidden by free people who were Black. Much of her story is known because of an 1845 interview in the Concord, New Hampshire, Granite Freeman, an abolitionist newspaper.

Neither the ad nor her story, however, were unique, Walker said. In analyzing the ads, he found a disproportionate number mention a suspected escape by water.

“As we start to go through them and look closely, a very large proportion of them provide information about how the person escaped, and that information indicates that it was in a state of water,” he said.

There is additional evidence of the importance of coastal ports to the Underground Railroad. William Still’s 1872 collection of narratives of escape from enslavement, “The Underground Rail Road,” has a significant number of stories focusing on fleeing in ships plying the East Coast.

Wilbur Siebert, one of the first historians to extensively research the Underground Railroad, wrote in his 1898 book, “The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom,” “The advantages of escape by boat were early discerned by slaves living near the coast or along inland rivers. Vessels engaged in our coastwise trade became more or less involved in transporting fugitives from Southern ports to Northern soil.”

And, Walker said, it was not surprising that enslaved people were able to use waterways for their escape. All the labor to move goods and products along the waterways of the South was supplied by enslaved people. They were the longshoremen and stevedores, the ship pilots — everyone who handled cargo and worked the docks was an enslaved person.

“The absolute fundamental bedrock reason for why escape by water worked and the conditions existed to get people out of places very, very far away from the free states was the labor force on the waterfront of the entire Southern Seaboard, every little inlet and port city and tidal waterway and river … down to the ports for loading onto larger ocean going vessels to take them to market. All of that labor was enslaved African American labor,” he said.

Research has also shown that, although most enslaved people fled north, not all of them did and there were significant communities of formerly enslaved peoples that come into existence in the Spanish-controlled areas of Florida, Texas and Mexico.

Dr. Maria Hammack of the University of Pennsylvania, also part of the symposium panel, has studied the phenomena. What she learned was that, although there were differences between how the United States’ Underground Railroad was implemented and that of the Mexican version, the human element remained constant.

“I have come to understand that the Underground Railroad was this organized network of assistance that led north with conductors and safe houses. And I wanted to know if the Underground Railroad to Mexico materialized in the same way,” she said. “What I have learned is that it did materialize very differently, but essentially, it was people who led it.”

Because so much of how the Underground Railroad operated was not recorded—could not be recorded—there is no way to know how many people found their way to freedom. But Dr. Adrienne Israel, retired Guilford University professor of history and another member of the panel, noted that the number was less important than what it symbolized.

“It doesn’t matter so much how many people actually escaped,” she said. “It’s the perception of the slave folks that really gave this underground railroad it’s impact.

“It is the notion that we should be free, we can be free,” she said.