CAPE HATTERAS — This year is the 50th anniversary of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Marine Sanctuary Systems, an occasion that by definition makes the Monitor National Marine Sanctuary extra special because it was the very first one.

The problem is that most Americans may be thinking: “What’s a marine sanctuary system?” And even if the public is aware that they exist, do they understand their purpose?

Supporter Spotlight

“Not nearly enough,” John Armor, director of NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, said in a recent interview. “We have a lot of work to do on that.”

Next week, the public can see for themselves the value a sanctuary offers. From Sunday, May 15, through Wednesday, May 25, people will have a golden opportunity to watch groundbreaking science livestreamed during a new expedition at the Monitor National Marine Sanctuary.

According to a NOAA press release, a team of scientists and divers working off NOAA Ship Nancy Foster as a research platform will employ state-of-the-art technologies, including underwater drones, to explore the Monitor Civil War ironclad and other shipwrecks in the surrounding area as part of a study on their value as fish reefs.

Described by NOAA on its website as a “network of underwater parks,” the sanctuary system totals more than 620,000 square miles and includes 15 national marine sanctuaries on Atlantic, Pacific and Gulf coasts, American Samoa and the Great Lakes, as well as the Papahānaumokuākea and Rose Atoll marine national monuments.

The National Marine Sanctuary System turns 50 on Oct. 23.

Supporter Spotlight

“I think the 50th anniversary is really an opportunity for us to sort of expand the tent and bring a lot more awareness to and frankly appreciation for them and love of the National Marine Sanctuaries system more broadly,” Armor said.

Armor, who has been at the helm since 2016, said that current efforts are focused on connecting local communities more to the sanctuary’s work. Sanctuaries also need to be more accessible, including engagement with tribal and indigenous communities, he said. And its workforce needs to be more diverse.

When the sanctuary system was created in 1972 with passage of The Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act, it was one of a series of landmark coastal protection bills enacted around that time, which also included the Coastal Zone Management Act, the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the Magnuson Fishery Conservation and Management Act, the Clean Water Act and the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act Amendments, according to NOAA’s online history of the system.

But it took three years for the first sanctuary to come to fruition, and it was fortuitous timing that the Monitor was discovered about 20 miles off Cape Hatteras by Duke University researchers the year after the system was created.

A centerpiece

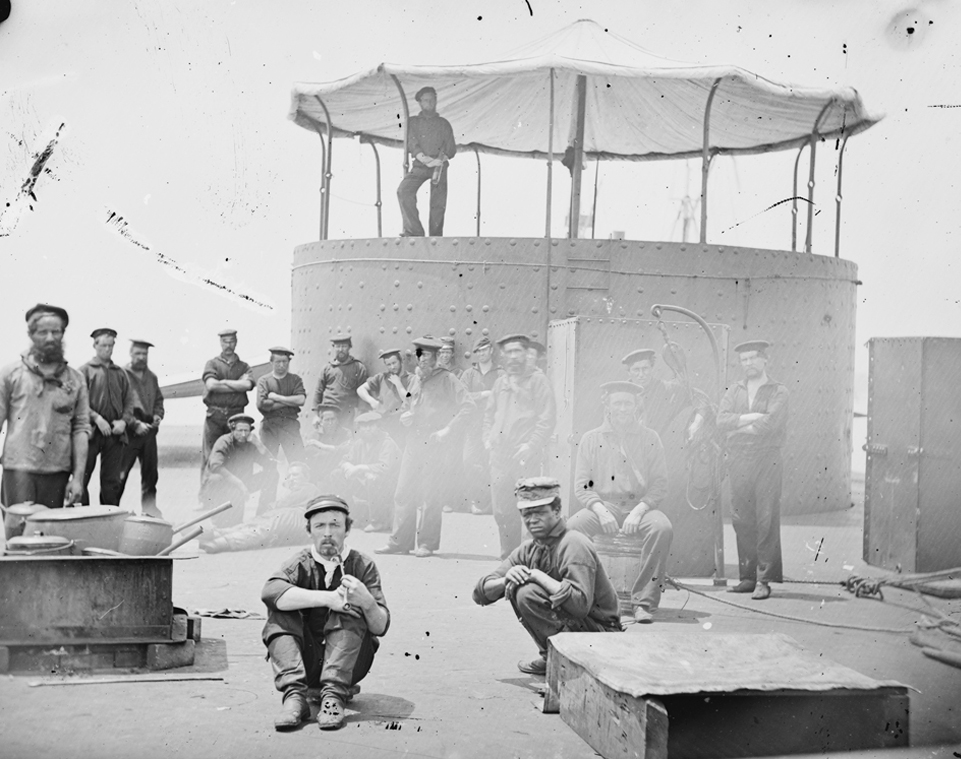

From the moment the USS Monitor steamed into Hampton Roads in early 1862, the Union Navy’s first ironclad dazzled as a wartime engineering phenomenon. Its nearly four-hour battle less than two months later in a Norfolk harbor with the Confederate ironclad CSS Virginia ultimately came to a draw but sealed its heroic legacy.

Even after the famed battleship and its 16 officers and crew went down that same year during a vicious New Year’s Eve gale, the Monitor remained a centerpiece of scientific and cultural interest.

Situated in the notorious “Graveyard of the Atlantic” — feared by mariners for its shifting, shallow shoals — the sunken vessel sits on the ocean floor 230 feet deep in a column of water a nautical mile in diameter. The site was designated as the nation’s first marine sanctuary Jan. 30, 1975.

Thousands of artifacts have been recovered from the Monitor, most of which are housed at The Mariners Museum in Newport News, Virginia. In 2001, NOAA, the U.S. Navy and The Mariners Museum, among others, partnered in five expeditions to retrieve numerous artifacts, including its steam engine and a section of the hull. The next year, the Monitor’s revolving turret was brought up from the ocean floor in a 42-day expedition.

When the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum in Hatteras, part of the North Carolina Maritime Museum system, completes its exhibit installation in the coming months, it anticipates including artifacts from the Monitor.

The original impetus for the Hatteras museum was spurred by the discovery of the Monitor wreck, but planning and funding difficulties delayed the project until long after the artifacts had gone to Virginia.

In 2008, the Monitor Sanctuary proposed expanding its parameters to include some sunken war wrecks in the vicinity, including World War II U-boats. But after a series of public meetings in which local divers and fishers expressed concerns about increased restrictions, the proposed plan was tabled.

NOAA, meanwhile, says that Navy regulations provide protections for the sunken vessels.

But Armor said that the expansion plan could be restarted, with more public input. Currently, NOAA is working to establish new sanctuaries off Hawaii and the south-central coast of California.

Once those planning processes are finalized, which could happen within 18 months or so, then the proposed expansion of the Monitor Sanctuary could potentially be reconsidered, he said.

Open process

Armor said he understands community suspicion or skepticism about restrictions, but he assured that each sanctuary has its own specific plan, with its own set of regulations and permitted activities that are developed by, with and for the community.

“That’s the thing that we love about the sanctuary process, is it is so open and collaborative,” he said. “We really go a long ways to making sure that we’re engaging all sectors of potentially affected communities in the decision and really benefit from guidance and perspective that communities have to offer. So, there’s not a one-size-fits-all approach to any of these topics that would come from the national office.”

Enforcement, also, is done on a site-by-site basis by the NOAA Office of Law Enforcement, which works closely with the Coast Guard and state wildlife agencies.

While activities such as diving and fishing are permitted in most areas of marine sanctuaries, Armor said, they also provide refuge to fish and other sea life, foster resilience and allow for almost real-time scientific monitoring to protect habitat and water quality.

And marine sanctuaries help in addressing an issue, he said, “that can be too big for people to even wrap their minds around.”

“I think the impacts of climate change and how they’re being felt in communities across the country has really highlighted the value that National Marine Sanctuaries can bring to the problem,” he said. “And so, sanctuaries and other protected areas on land and in the ocean help us focus our attention and help us focus our messaging on what we can do as average citizens to help address these challenges.”

Armor said that NOAA is planning a series of events leading up to the October anniversary celebration, which are detailed on a newly updated website.

It’s all part of getting the word out to the public, so they can celebrate what most didn’t even know they had.

“And again, using the 50th anniversary not to look backwards and pat ourselves on the back for all the great things we’ve done,” he said, “but to challenge ourselves and to look forward to how we can do better down the road.”