March is Women’s History Month.

Civil rights and women’s suffrage pioneer Annie E. Jones of Elizabeth City is to be recognized with a historic marker in the Pasquotank County seat.

Supporter Spotlight

It’s unlikely her name will be in history books and it’s doubtful that there will be a movie made of her life, but Dr. Melissa Stuckey, assistant professor of history at Elizabeth City State University, is working to make the name Annie E. Jones known.

The William Pomeroy Foundation, which supports community history and blood cancer patients, is funding through its National Women’s Suffrage program a historic marker recognizing Annie E. Jones on the National Votes for Women Trail, a project of the National Collaborative for Women’s History Sites honoring women’s suffrage efforts leading to the passage of the 19th Amendment, Stuckey wrote in a column in the Elizabeth City Daily Advance.

The marker is expected to be placed sometime this fall at the intersection of Road and Speed streets on property owned by Cornerstone Missionary Baptist Church, her longtime church, Stuckey told Coastal Review.

Annie E. Jones, who was born in 1884 and died in 1950, advocated for African American women’s voting rights and organized voter education classes after the 19th Amendment, which gave women the right to vote, was passed Aug. 18, 1920, according to the foundation.

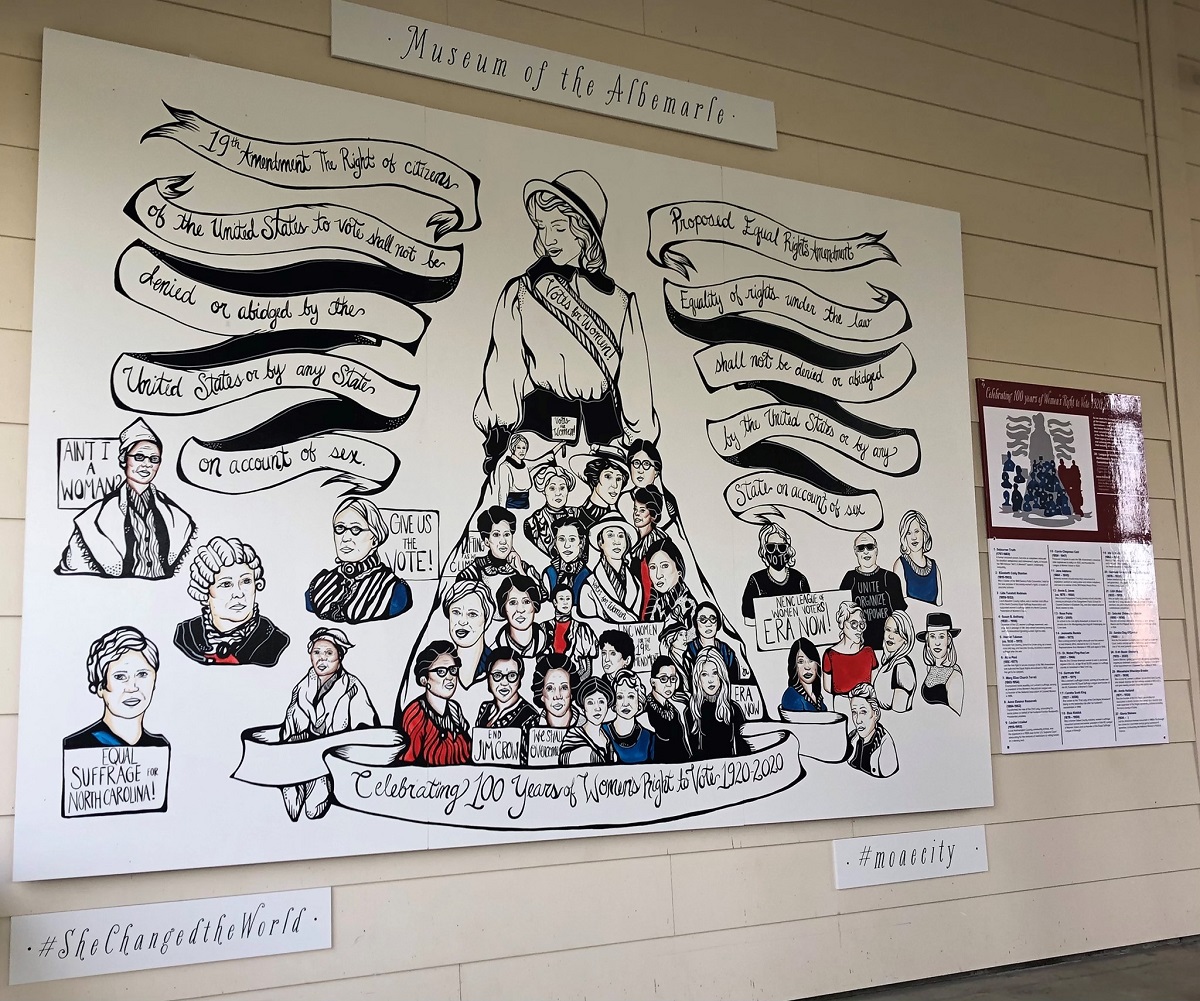

A graduate of the Elizabeth City State Colored Normal School in 1901, now Elizabeth City State University, and resident of Speed Street until her death, she was a respected teacher and principal. Annie E. Jones was a member of several clubs including the Elizabeth City Matrons’ Social and Literary Club that was affiliated with the State Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs. She is also featured on a mural with other prominent northeastern North Carolina women that celebrates 100 years of women’s right to vote at the Museum of the Albemarle in Elizabeth City.

Supporter Spotlight

For Stuckey, who did much of the research in establishing the historic significance of Annie E. Jones’ efforts, the passage of the 19th Amendment was a remarkable opportunity to change the arc of history.

“Black women strategically have an opportunity to attempt to vote and challenge Black disfranchisement in a different way,” she said about the passage of the 19th Amendment.

It was an opportunity educator Annie E. Jones hoped to capitalize on, too. The Elizabeth City Independent described her in its July 21, 1922, edition as, “one of the most capable, most thorough and most conscientious primary school teachers in North Carolina.”

However, this is a period where African American men “have been brutally disenfranchised in North Carolina with violence,” Stuckey told Coastal Review, specifically pointing to the Wilmington race riot of 1898.

There were also requirements Black men had to meet in order to vote, including pay $2 poll tax – about $60 in today’s money – and must be able to read and write any section of the Constitution, states a 10-page pamphlet, “What a Colored Man Should Do To Vote,” written sometime between 1900 and 1909 and part of the Library of Congress collection that lists requirements by state in the South.

Even if a Black man were able to pass the voting requirement test and pay the poll tax, threats to livelihood and life were common.

In an interview with Coastal Review last year, Marvin Tupper Jones, executive director of the Chowan Discovery Group, gave an example of the violence directed toward people of color as they attempted to vote.

“In 1898 the same year and the same time as the Wilmington race riot, word got out in the morning of the election in Winton that a lot of people of color were voting, and the guns came out. So people of color stopped voting that afternoon in Winton,” he said.

The violence that Marvin Tupper Jones describes was not limited to the South, Stuckey explained to Coastal Review, “that was the case for places across the nation.”

However, the passage of the 19th Amendment gave women of color a chance to change the narrative.

It was Annie E. Jones’ goal, she told the Independent of Elizabeth City in September of 1920, that the Black women of the city and Pasquotank County would be better informed and use the power of the ballot more effectively than the men had.

“We realize,” the Independent quoted her as saying, “That our colored men did not use the ballot intelligently and for their best interests when they had it; they blindly followed the selfish leaders of one political party and never did any thinking for themselves. Most men don’t know anything about government anyway. We colored women are going to know the subject of government from the township unit up to the national congress and most of us already can show you how to read and interpret the Constitution of the United States.”

While the statement seems harsh, Stuckey explained that there was more to Annie E. Jones’ words than meets the eye, by necessity. Black society would often present one face to the world while preserving their true feelings for the people they could trust.

In the study of Black history, Stuckey explained, there are a couple of themes or tropes that are repeated that people use to protect themselves when they are dealing with adversity.

“W.E.B. DuBois refers to it as a veil, where there is a double (consciousness), that African American people have; a face that they show to the white power structures and people around them, and they have their own personal face that they share within their community,” she said.

That veil was essential if there was any hope of registering Black women to vote. “It was incumbent upon someone like Jones, to assuage any kinds of concerns that white men would have about them participating in the ballot,” Stuckey explained.

For any Black woman hoping to vote, it was important that they distance themselves from their husbands, fathers and sons who overwhelmingly voted for Republicans. The Democratic Party in the South at that time was often a self-described white supremacy organization.

In North Carolina, the Democratic Party-led legislature passed an amendment to the state constitution requiring a poll tax and literacy to vote.

“The primary goal of the amendment, as admitted in the Democratic Party’s pro-amendment campaign in 1900, was to eliminate African American voters as a factor in North Carolina politics,” according to NCPedia, an online reference managed by the North Carolina Government & Heritage Library at the State Library of North Carolina.

Annie E. Jones and other women of color understood that they had to give the appearance of neutrality. Nonetheless, they faced significant headwinds. “There was a counter-organizing attempt to really intimidate Black women so that they would not register to vote,” Stuckey said.

Black women faced overt racism over the news that they could gain the right to vote.

The Sept. 24, 1920, edition of the Monroe Journal in Union County published a letter from Mrs. J. Frank Laney under a headline reading, “Mrs. Laney Says Women by Instinct are Democratic. She Favors the ‘White Party’ and Urges Young Voters to Read ‘The Clansman.’”

Laney went on to write, “Let our young women of voting age read such books as ‘The Call of the South’ and ‘The Clansman,’ therein detecting the sinister cloud of the dark-skinned Americans …”

Another example of what Black women faced in their struggle to register to vote was in the Greensboro Patriot. An Oct.19, 1920, editorial on a letter that purported to support suffrage for people of color concluded with, “The Patriot … takes pride in being a Greensboro — White Supremacy — Democratic newspaper every day in the year.”

The threats of violence and loss of livelihood had the desired effect, Stuckey said. “It was a very successful venture in terms of intimidation tactics … threatening employment in particular, whether for the woman herself or for the husband. The registrar reported that only three Black women registered to vote (in Pasquotank County, 1920).”

Stuckey said she has not been able to locate the 1920 voter registration records for the county, so it’s unclear if Annie E. Jones was one of the women who did register. But whether she was one of those voters in 1920, it does not change how important she was in the fight for equal rights.

“She’s a powerful civil rights figure. She’s powerful women’s rights figure,” Stuckey said.