SOUTHPORT – Steve Stone wasn’t buying it.

“That doesn’t convince me of anything,” Stone said Friday while staring at what could have passed for a solid black sheet of paper during an event in Southport hosted by the advocacy group Offshore Wind for North Carolina.

Supporter Spotlight

Stone was studying a visual simulation of what was identified as a starlit night over the Atlantic Ocean as seen from the shore at Holden Beach.

The 11-inch by 17-inch print was propped on an easel at one end of a row of easels, each holding photographs meant to give people an idea of what they might see of offshore wind farms from the vantage point of various Brunswick County beaches.

“My frustration (is that) it’s not credible, in part because of the scale of those pictures,” Stone said later on that frigid morning outside of the Southport Community Building. “If it needs to happen, we just need ways to calm down some of the public’s concerns. Ambiguity scares people.”

The “it” to which he referred is offshore wind turbines, a renewable energy source being considered for development off of North Carolina’s northern and southern coastal areas.

Stone, who last month officially transitioned from his job as Brunswick County’s deputy manager to manager and declared himself neutral on wind turbines off the county’s shore, was an early attendee of the open house.

Supporter Spotlight

His sentiments were echoed by some in the small circles of residents and beach town officials who went to the open house hoping to learn more about what a wind farm several miles from the county’s beach shorelines might mean — good or bad — for the area.

Those who spoke to Coastal Review overwhelmingly said they support renewable energy alternatives but expressed skepticism about what they said was a general lack of information. But that’s because decisions are yet to be made.

“I do think maybe what’s most important right now is how early on we are in this process,” explained Jaime Simmons, program manager for the Southeastern Wind Coalition, which commissioned the visualizations. “There is a lot of time. A lot of things are undetermined.”

The federal government has identified two wind energy areas, or WEAs, off the state’s coast for potential commercial wind energy development: the Kitty Hawk WEA and Wilmington East WEA.

The government scrubbed a third area identified as the Wilmington West WEA, which was as close as 10 nautical miles from shore, citing visual concerns.

Brunswick County beach town leaders, as well as county officials, have pushed back on the prospect of wind farms being built within the viewshed, or within sight of shore.

Last year, the Village of Bald Head Island Council adopted a resolution urging the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, or BOEM, to establish a buffer for offshore wind energy leases, allowing them no closer than 24 nautical miles, or about 27 miles, off North Carolina’s southern coast.

That resolution was similar to one the village council adopted in 2015. After the council adopted its resolution in 2021, other Brunswick County beach towns and the Brunswick County commissioners followed suit.

Related: Brunswick officials’ worries over offshore wind unresolved

BOEM has also established a 24-nautical-mile no-leasing buffer for Virginia and the Kitty Hawk WEA. A 33.7-nautical-mile no-leasing buffer has been established to protect the Bodie Island Lighthouse.

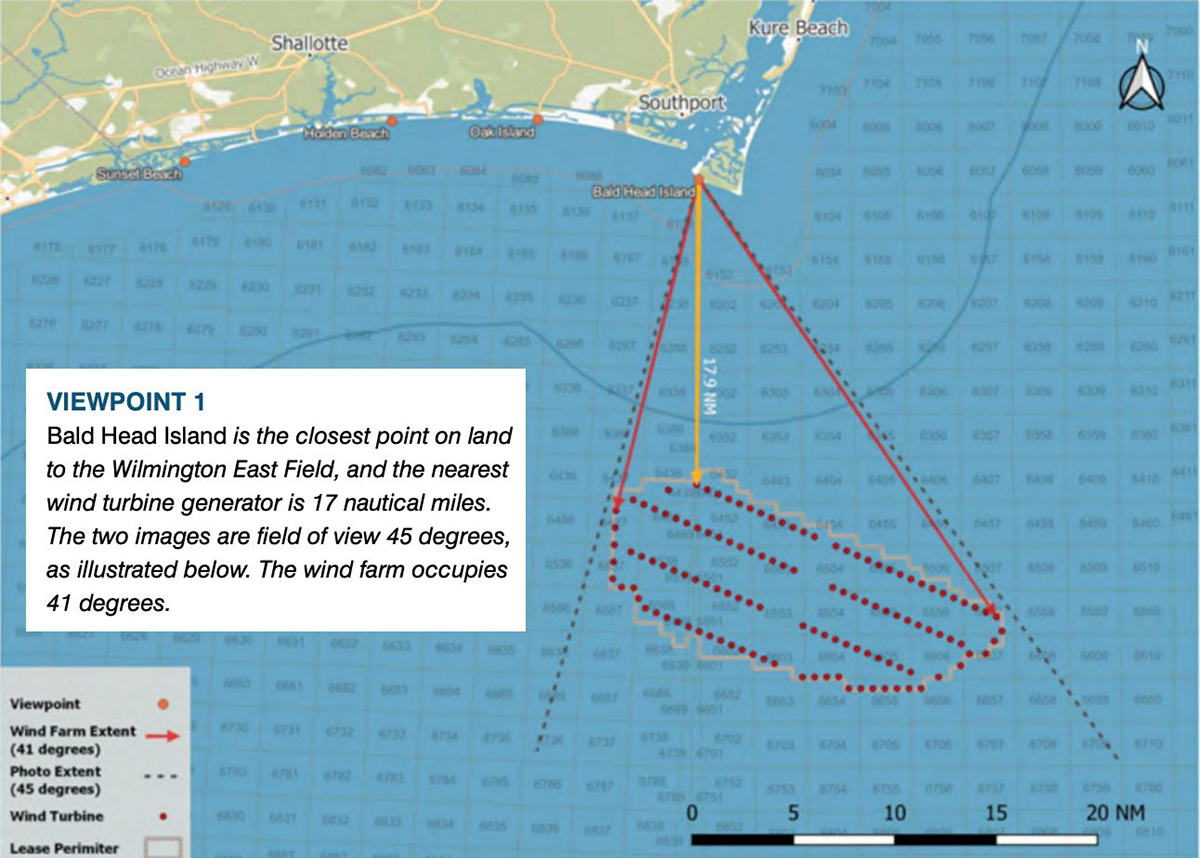

The Wilmington East WEA begins at its closest point to land about 17 nautical miles from Bald Head Island.

The coalition’s visual simulations presented during the open house showed three viewpoints on both clear days and days with haze from ultraviolet rays from the three beaches closest to the wind energy area: Bald Head Island, Oak Island and Holden Beach.

The United Kingdom-based company UNASYS, which specializes in large-scale energy transition processes, produced the visualizations using imagery from BOEM.

In most of the images presented to the public last week, the wind turbines were mostly undetectable. In one of the images taken from the shores of Holden Beach, tiny specks along the horizon could be seen, but just barely.

The lease area may hold up to an estimated 122 wind turbines and generate enough energy to power more than 500,000 homes. Turbines modeled in the images are based on the industry standard, which is about 850 feet tall.

It remains unclear where the energy that’s produced offshore will be tied into the power grid on land. Murmurs of speculation about the possibilities — some as far north as New Bern — could be heard among the small groups of people at the open house.

A lease auction of the area is expected to be held sometime in April or May, part of what is about the second year in what is anticipated to be about a 10-year process, Simmons said.

Simmons briefly redirected her attention while speaking with Coastal Review to answer a question from Oak Island resident and recreational fisherman Dave Ries.

“Are we actually going to be able to fish in that area?” he asked.

Simmons responded that the U.S. Coast Guard has said it has no intentions of restricting fishing around wind turbines. Her answer seemed to satisfy Ries.

“That was my primary problem with it,” Ries said, a smile on his face as he turned and headed to a door of the community building nestled on a riverfront street with a view of Bald Head Island.

Members of the North Carolina For-Hire Captain’s Association have far more questions about the potential impacts of wind turbines on fish and bird migrations and the underwater environment.

“We can’t get any information,” said Cane Faircloth, a fishing charter captain from Holden Beach. “It’s almost like it’s taboo. Once they’re up, they’re not going to take them down.”

Faircloth questioned whether sound from the large, spinning rotors would deter fishermen from getting close enough to fish around turbines.

“I think you would be uncomfortable around them,” he said.

Southport resident and fishing charter captain John Dosher raised concerns about how the installation of turbines might affect the ocean floor’s topography.

“I would never be against renewable energies,” he said. “When you’re talking about putting these things down, you’re changing an ecosystem and an estuary. The environment is the biggest thing. What kind of environmental impacts are we talking about?”

The men also questioned how well turbines can withstand hurricane winds and what kinds of infrastructure, including roadways, would be needed to get turbines from land to sea. They wondered about the need for additional boat fueling stations for vessels carrying supplies and workers between a wind farm and land and about the overall efficiency of the turbines themselves.

“It just seems like we have everything to lose and nothing to gain from this,” Faircloth said.

Randy Sturgill, senior field representative with the advocacy group Oceana, said during the open house that the organization would be closely tracking the environmental process.

“We’re thrilled to see all the progress to advance clean offshore wind energy,” he responded to Coastal Review in an emailed statement. “As this project moves forward, we’ll be monitoring and engaging with the environmental reviews and seeking to ensure that the highest mitigation standards are required so that offshore wind can advance in a responsible and environmentally friendly way. As these projects move forward, we’re seeking that the highest mitigation standards are required for critically endangered species like the North Atlantic right whale.”

Simmons said there are companies in North Carolina that provide land-based manufacturing, including one that makes fiberglass coatings for wind turbines, and an onshore cable manufacturer.

Turbine manufacturers exist largely in European countries and offshore wind advocates say that coastal areas of North Carolina could secure some of the first such manufacturers in North America.

“There’s a huge opportunity that we’re just on the cusp of,” Simmons said.

Jennifer Mundt, North Carolina Department of Commerce assistant secretary of Clean Energy Economic Development, agreed.

“This is a huge industry that is growing right now,” she said. “The opportunities are boundless.”