Editor’s note: Coastal Review is sharing this work by historian David Cecelski in recognition of Black History Month.

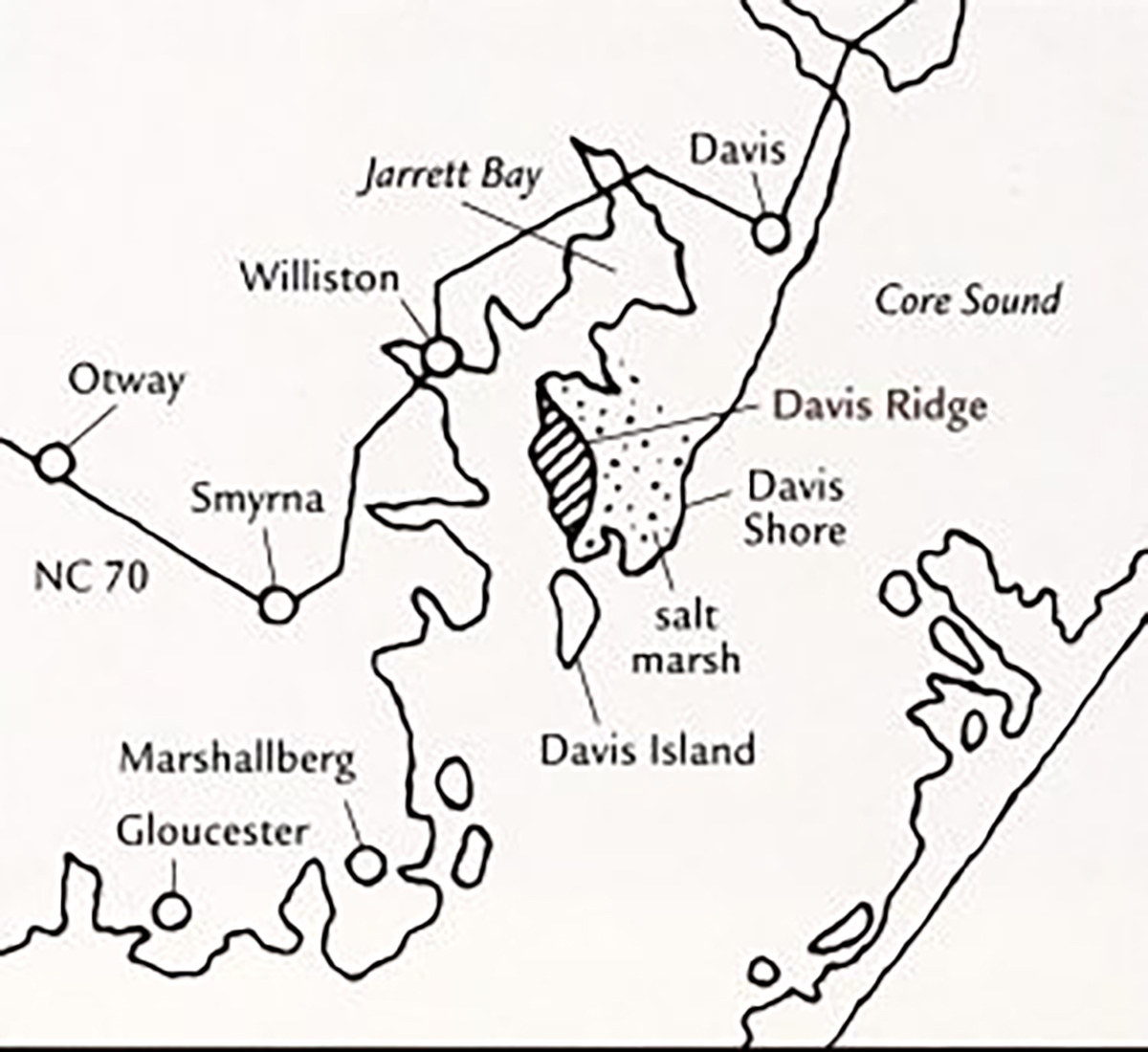

Whenever I pass the old clam house between Smyrna and Williston, I glance east across Jarrett Bay to Davis Ridge. You will go that way if you drive Highway 70 across the broad salt marshes of Carteret County, to catch the Cedar Island ferry to the Outer Banks.

Supporter Spotlight

Most passersby admire the beautiful vistas across Core Sound and look for the wild ponies grazing in the Cape Lookout National Seashore and the Cedar Island National Wildlife Refuge. Some travelers wander through the old seaside villages, such as Harkers Island, that are renowned for their boatbuilding, fishing and seafaring heritage.

Few coastal visitors know that the secluded hammock of Davis Ridge was once home to an extraordinary community founded by liberated slaves.

Nobody has lived at “the Ridge” since 1933, yet the legend of those African American fishermen, whalers and boatbuilders still echoes among the elderly people in the maritime communities between North River and Cedar Island that locals call Down East.

This essay appeared in my book “The Waterman’s Song: Slavery and Freedom in Maritime North Carolina” (University of North Carolina Press, 2001). It was originally a lecture at a conference on race, power and ethnicity in maritime America that was held at Mystic Seaport in Mystic, Connecticut. Earlier versions of the essay appeared in Coastwatch magazine and Sea History.

At the North Carolina Maritime Museum

I had heard of Davis Ridge when I was growing up 25 miles to the west. When I became a historian, I searched for the history of those Black Down Easterners with much ardor and little success.

For a long time, I assumed all record of them had been lost. I found no trace of Davis Ridge in history books. Exploring the Ridge by boat and on foot, I uncovered only an old cemetery in a live oak grove surrounded by salt marsh and, only a few yards away, Core Sound and Jarrett Bay.

Supporter Spotlight

All the documents that I examined in research libraries, archives and museums yielded only tantalizing clues to the community’s past. The best sources I could find were a few, mostly secondhand recollections from elderly people who had grown up in fishing villages not far from Davis Ridge.

At last, after I had given up I stumbled upon a tape-recorded interview with Nannie Davis Ward in a storage pantry at the North Carolina Maritime Museum in Beaufort.

Most success in historical research comes from persistence and hard work. Finding Ward’s interview was an undeserved act of grace.

Folklorists Michael and Debbie Luster had interviewed Ward in 1988 only a few years before her death. At that time, Ward was apparently the last living soul to have grown up at Davis Ridge.

A retired seamstress and cook, she was born at the Ridge in 1911. Ward was blind by the time the Lusters interviewed her, but she had a strong memory and a firm voice. Listening to her eloquent words, I found a vivid portrait of her childhood home taking shape in my mind. Her story fills an important part of the history of the African American maritime people who inhabited the coastal villages and fishing camps of North Carolina before the Civil War.

It is a story of only one community, Davis Ridge, but it speaks to the broader experience of the Black watermen and women who came out of slavery and continued to work on the water.

Black maritime traditions before the Civil War

When Nannie Davis Ward was a child, Davis Ridge was an all-Black community on a wooded knoll, or small island, on the eastern shore of Jarrett Bay, not far from Core Sound and Cape Lookout. A great salt marsh separated the Ridge from the mainland to the north, which was known as Davis Shore. Davis Island was just to the south. A hurricane cut a channel between Davis Ridge and Davis Island in 1899, but in her grandparents’ day it had been possible to walk from one to the other.

The founders of Davis Ridge had been among many slave watermen and women at Core Sound before the Civil War. Ward’s family was in many ways typical of the African American families along the Lower Banks. They were skilled maritime laborers with a seafaring heritage. They had 18th century family roots in the West Indies and had Black, white and Native American ancestry. They moved seasonally from fishery to fishery, working on inshore waters, rarely the open sea.

They also had a history of slave resistance. Nannie Davis Ward’s mother, who identified herself as Native American, had grown up in Bogue Banks, a 26-mile-long barrier island west of Beaufort, and her mother’s grandfather had evidently been a slave aboard a French sailing vessel. According to Ward, that great-grandfather had escaped from his French master while in port at New Bern and had been raised free in the family of a white waterman at Harkers Island, 10 miles west of Davis Ridge.

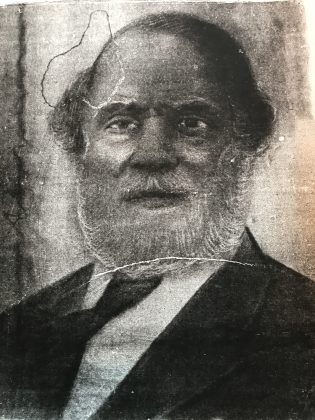

It was Sutton Davis, Ward’s paternal grandfather, who first settled Davis Ridge. As a slave, Sutton Davis had belonged to a small planter and shipbuilder named Nathan Davis at Davis Island. Sutton Davis had been a master boatbuilder and carpenter. According to his granddaughter, he had learned the boatbuilding trade at a Wilmington shipyard owned by a member of the white Davis family and then moved back to Davis Island.

Family lore on one side of the white Davis family holds that Nathan was Sutton’s father. Nannie Davis Ward did not address that question in her interview, except to note that Sutton and his children were very light skinned.

A voyage to freedom

When Union troops captured Beaufort and New Bern in 1862, Sutton Davis led the Davis Island slaves to freedom. They rowed a small boat across Jarrett Bay to the fishing village of Smyrna, from where they fled to Union-occupied territory on the outskirts of New Bern.

After the war, some of those former enslaved people founded the North River community, a few miles outside of Beaufort, but Sutton Davis bought 4 acres at Davis Ridge in 1865. Nathan Davis sold him the property for the sort of low price usually reserved for family. Sutton Davis and his children eventually acquired 220 more acres at Davis Ridge.

The number of Black Down Easterners declined sharply after the Civil War, but Davis Ridge remained a stronghold of the African American maritime culture that had thrived along Core Sound. Nearly all of Nannie Davis Ward’s relatives worked on the water. Her grandfather Sutton, of course, was a fisherman and boatbuilder. Her mother’s father, a free Black man named Samuel Windsor, became a legendary fisherman and whaler at Shackleford Banks, the 9-mile-long barrier island just east of Beaufort. Sam Windsor’s Lump is still marked on nautical charts of Shackleford.

Her father, Elijah, owned a fish house. Her great-uncle Palmer was a seafarer and sharpie captain. Her great-uncle Adrian was a captain of the fishing boat Belford. Another great-uncle, Proctor, was a waterman who lived at Quinine Point, the northwest corner of Davis Ridge.

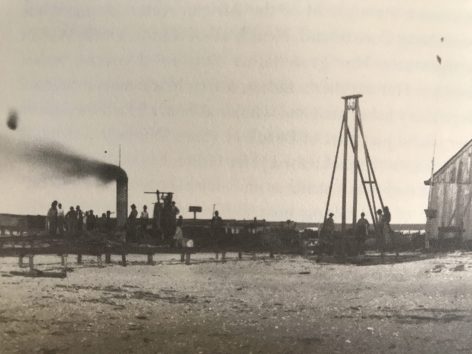

Many other kinsmen became stalwarts in the Beaufort menhaden fleet, which rose in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to become the state’s most important saltwater fishery. During its heyday, Black watermen dominated the menhaden fishery, which had Black leadership earlier than any other local industry. Out of Nannie Davis Ward’s family came the menhaden industry’s first African American captains.

Saltwater farmers

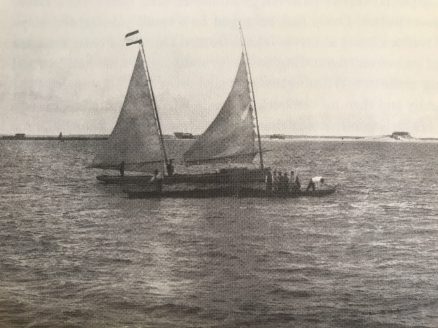

Sutton Davis and his 13 children operated one of the first successful menhaden factories in North Carolina, long before the industry’s boom in Beaufort. Sutton built two fishing schooners, the Mary E. Reeves and the Shamrock. His sons worked the boats while his daughters dried and pressed the menhaden — known locally as “shad” or “pogie” — to sell as fertilizer and oil.

“Men should have been doing it,” Ward explained, “but he didn’t have them there, so the girls had to fill in for them.”

In fact, Ward pointed out, at Davis Ridge, “The girls did a lot of farm working, factory work too.”

The Black families at Davis Ridge were what local historian Norman Gillikin in Smyrna calls “saltwater farmers”: the old-time Down Easterners who lived by both fishing and farming. They hawked oysters across Jarrett Bay and raised hogs, sheep and cattle. They grew corn for the animals and sweet “roasting ears” for themselves. At night they spun homegrown cotton into cloth.

Their gardens were full of collard greens and, as Ward recalled vividly, “sweet potatoes as big as your head.” They worked hard and prospered.

Sometimes Sutton Davis augmented his children’s labor by hiring fishing hands from Craven Corner, an African American community 30 miles west. Craven Corner had been settled in the 18th century by free Blacks that had migrated south out of Virginia. According to local oral tradition, many had intermarried with the descendants of the Native American survivors of the Tuscarora War of 1711-13. Over the generations, African Americans at Craven Corner had earned a strong reputation for a fierce independence and for being excellent watermen and artisans.

One does not have to stretch one’s imagination to see them fitting into the fishing life at Davis Ridge.

Davis Ridge was a proud, independent community. When Nannie Ward was growing up there in the 1910s and 1920s, seven families — all kin to Sutton Davis — still lived at the Ridge. They sailed across Jarrett Bay to a Smyrna gristmill to grind their corn and to a Williston grocery to barter fish for coffee and sugar, but mainly relied on their own land and labor.

They conducted business with their white neighbors at Davis Shore or across Jarrett Bay by barter and by trading chores. “You didn’t know what it was to pay bills,” Ward reminisced.

Island women

While the Davis Ridge men worked away at Core Banks mullet camps or chased menhaden into Virginia waters, the island women cared for farms and homes. They gathered tansy, sassafras and other wild herbs for medicines and seasoning. Thy collected yaupon leaves in February, chopped them into small pieces and dried them to make tea.

In May, they sheared the sheep. Nannie Ward’s grandmother spun and wove the wool. They produced, Ward explained, “everything they used.”

Davis Ridge was a remote hammock, but Ward could not remember a day of loneliness or boredom. She told how two Beaufort menhaden fishermen, William Henry Fulcher and John Henry, used to visit and play music on her front porch.

“We enjoyed ourselves on the island,” Ward said. “There wasn’t a whole lot of things to do, but we enjoyed people. We visited each other.”

The camaraderie of Black and white neighbors around Davis Ridge was still striking to Nannie Ward a century later. For most Blacks in coastal North Carolina, the 1910s and 1920s were years of hardship and fear. White citizens enforced racial segregation at gunpoint. Blacks who tried to climb “above their place” invited harsh reprisals. The Ku Klux Klan marched by the hundreds in coastal communities as nearby as Morehead City, and word went out in several fishing communities — including Knotts Island, Stumpy Point and Atlantic — that a Black man might not live long if he lingered after dark.

Davis Ridge was somehow different. Black and white families often worked, socialized and worshiped together. “The people from Williston would come over to our island,” Ward said of school recitals and plays, “and we’d go over to their place.”

Sutton Davis’s home, in particular, was a popular meeting place. Hymn singers of both races visited his home at Davis Ridge to enjoy good company and the finest pipe organ around Jarrett Bay.

Ward even recalled a white midwife staying with Black families at Davis Ridge when a child was about to be born, a simple act of kindness and duty that turned racial conventions of the day upside down. This may seem a trivial thing, but it was quite the opposite.

A coastal midwife had to move into an expectant mother’s home well before her due date or risk not being in attendance at the birth because of the time required to travel to and from the islands. The midwife stayed for the child’s birth and then tended to mother and child — and sometimes the cooking and housework — until the mother was recovered fully. Taking care of those duties, a midwife could easily spend two or three weeks living in the mother’s household.

In the American South during the era of Jim Crow, it was not unusual at all for a Black midwife to serve a white family in that capacity. The arrangement was entirely consistent with a traditional role of Black women serving as maids and nannies in white homes.

But to reverse the arrangement was unheard of. The white South simply did not allow one of its own to serve a Black woman. Even more fundamental to the complex racial landscape of the day, a white woman could never stay the night under a Black man’s roof, that being a breech of the sexual code that was at the heart of Jim Crow.

The daily conduct of Blacks and whites at Davis Ridge would have caused riots, lynchings or banishment in most southern places, including coastal towns 20 miles away.

Similarly, in the 1950s and 1960s, many white ministers across the American South lost their jobs for inviting Black choirs to sing at a church revival. Yet the Davis Ridge choir sang at revivals at the Missionary Baptist church at Davis Shore two generations before the civil rights movement.

An old legend even tells how, in 1871, Black and white worshipers rushed from a prayer meeting and together made a daring rescue of the crew and cargo of a ship, the Pontiac, shipwrecked at Cape Lookout.

Mullet camps

The work culture of mullet fishing on the barrier islands near Davis Ridge both reflected and reinforced this blurring of conventional racial lines. Every autumn all or most of the Davis Ridge men joined interracial mulleting gangs of four to 30 men tending seines, gill nets and dragnets along the beaches between Ocracoke Island and Bogue Banks.

During the 1870s and 1880s, that stretch of coastline supported the largest mullet fishery in the U.S. More than 30 vessels carried the salted fish out of Beaufort and Morehead City, and the Atlantic & North Carolina Railroad transported such large quantities that for generations local people referred to it as the “Old Mullet Road.”

Out on those remote islands, Black and white mullet fishermen lived, dined and worked together all autumn, temporarily sharing a life beyond the pale of the stricter racial barriers ashore. They worked side by side, handling sails and hauling nets, and every man’s gain depended on his crew’s collective sailing and fishing skills.

For most, a lot was riding on the mullet season. Local fisherman were a hand-to-mouth lot, and mulleting was one of the few fisheries that promised barter for flour, cornmeal and other staples necessary to fill a winter pantry, to say nothing of putting aside a little for Christmas or a bolt of calico that might save their wives a fortnight of late night weaving.

Every fisherman hoped for the strongest crew possible, and nobody worked the mullet nets or knew how to survive the vicious storms on the barrier islands better than the men from Davis Ridge. On those secluded shores, away from the prying eyes of the magistrates of Jim Crow, a man’s race might start to seem a little less important.

Work customs reflected this camaraderie and interdependence. Mullet fishermen traditionally worked on a “share system,” granting equal parts of their catch’s profits to every hand, no matter his race. Owners of boats and nets earned extra shares. Often they also voted by shares to settle work-related decisions. These were the sort of working conditions that might attract even the independent-minded souls of Davis Ridge to work alongside their white counterparts.

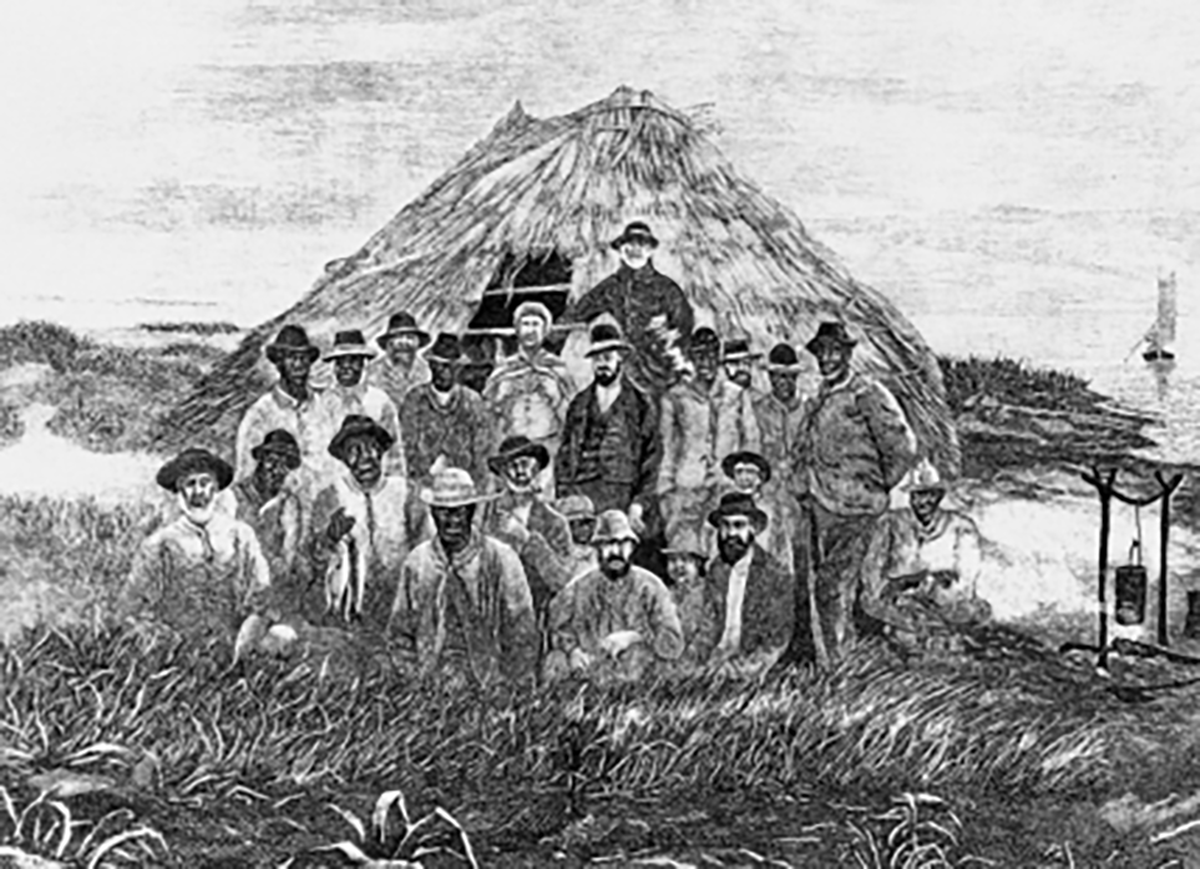

This fraternity of Black and white fishermen on the islands off Davis Ridge comes across clearly in a stunning engraving of a mulleting gang at Shackleford Banks. The original photograph on which the engraving as based was taken in about 1880 by R. Edward Earll, a fishery biologist who visited the local mulleting beaches as part of the U.S. Fish Commission’s monumental survey of all of the nation’s fisheries.

Look closely at the engraving and what stands out immediately are the equal numbers of Black and white fishermen, their intermingled pose, their close quarters, their obvious familiarity — one might even say chumminess — and the unclear lines of authority. All were entirely foreign to the standard racial attitudes of the American South in that day.

I find it one of the most extraordinary images ever made of life in the Jim Crow era. One never sees anything close to that intimacy and equality in the portraits of Black and white workers in cotton mills, lumber caps, coal mines or agricultural fields, much less in the trades or professions.

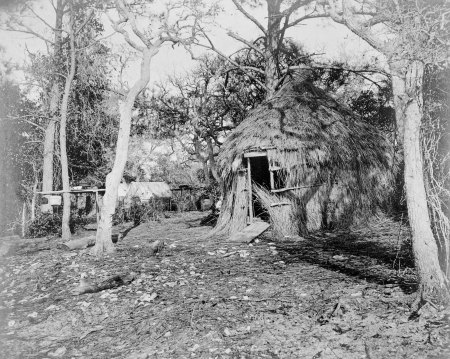

The notion of Blacks and whites sharing a fish camp whose design was inspired by a West African architectural tradition (see my book “The Waterman’s Song,” pages 78 and 248-49) stretches the imagination even farther.

A mullet fisherman from Davis Ridge may, in fact, have built the camp in this engraving. Sallie Salter, a white woman who lived near the Ridge from 1805 to 1903, recalled for her grandson that Proctor Davis “lived in a rush camp” at Davis Ridge and later moved closer to her family at Salter Creek “and built another rush camp, and lived in it for a long time.”

After dark

One must be careful not to exaggerate the racial harmony around Davis Ridge. Not a crossroads in the American South escaped the reality of racial oppression. Certainly Davis Ridge did not. After the statewide white supremacy campaigns of 1898 and 1900, local whites fostered an atmosphere of racial intimidation that increasingly drove African Americans out of Down East, as well as discouraged any new Black settlement in the villages east of North River.

For years, a hand-scrawled sign at the town limits of Atlantic, 15 nautical miles from Davis Ridge, read: “No Niggers after Dark.”

Even when I was a young boy, no Blacks lived anywhere Down East, and I often heard the admonition that African Americans could work in the Down East clam houses or oyster shucking sheds during the day but could never spend the night safely.

Once, on a club field trip to one of my teachers’ homes at Harkers Island, the teacher — a native of Down East — had the one African American girl in the club lay on the floor of her car as soon as she drove over the North River Bridge. My teacher did not have to explain why.

Seen in this light, Davis Ridge was an island in more than one sense: As the rest of Down East grew whiter and whiter after the Civil War, this remote knoll was increasingly seen as a last redoubt of African American independence and self-sufficiency. White fishermen could look across Jarrett Bay and refer to the Mary E. Reeves or the Shamrock as “the nigger boats,” as I have heard Down East old timers call them, but Sutton Davis’s clan still had two of the only menhaden boats Down East and the skills to make good money with them.

So many good things

That was the heart of the matter. Sutton Davis and his descendants could not remove themselves from the white supremacy pervasive in the American South but they had at least two advantages that most Black southerners could only dream of: land and a fair chance to make a living.

And, unlike the rest of the Jim Crow South, the broad waters of Core Sound could not so easily be segregated into separate and unequal sections. Self-reliant, in peonage to no one, the African Americans at Davis Ridge joined their white neighbors as rough equals in a common struggle to make a living from the sea.

Ward left Davis Ridge in 1925. She first went to Beaufort to attend high school, and then she moved to South Carolina and New York. While she was gone, the great 1933 hurricane laid waste to the island’s homes and fields. The Ridge was deserted when she returned in 1951. No African Americans resided anywhere Down East by that time.

“I still loved the island,” Ward told the Lusters only a few years before she died in Beaufort. “When you grow up there from a child, you learn all the things in the island, you learn how to survive. You learn everything.”

I heard a low, wistful sigh and a deep yearning in her voice. “We were surrounded by so many good things that I don’t get anymore, that I never did get again.” I knew that she was not speaking merely of roast mullet and fresh figs.

She was silent a moment. Then, with a laugh, she exclaimed, “I’d like to be there right now.”

Coastal Review is featuring the work of historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.