The “S-curves” north of Rodanthe, one of the most troubled sections of the ribbon of highway connecting Hatteras Island with the mainland, may soon be allowed to return to its natural state.

Sometime in March, if the weather holds and the North Carolina Department of Transportation meets its schedule, the span informally known as the “jug-handle” bridge will open to vehicle traffic, bypassing one of the most dynamic stretches of shoreline on Hatteras Island. Soon after the bridge opens, NCDOT is expected to remove the asphalt and the sandbags placed to protect it from land that is part of Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge, allowing the forces of nature to dictate what happens next.

Supporter Spotlight

“The jug handle has an opportunity to be a barrier island again and function as a barrier island. Not as a Highway 12 dune-dike complex,” East Carolina University geology professor Dr. Stanley Riggs told Coastal Review last week.

It is a stretch of shoreline has always been dynamic. Wimble Shoals is just to the south of the beach, and buried beneath the sandy shoal is rock. That rock has lot to do with why it is one of the best beaches for surfing on the Outer Banks, Riggs explained.

“When we get heavy weather, the waves still refract off that rock, which is why that’s such an important surfing area,” he said.

The wave energy, though, is not the only factor that will affect what happens when the road is gone.

“This is actually something that I have been thinking about,” said Dr. Reide Corbett, dean of Integrated Coastal Programs at ECU’s Coastal Studies Institute in Wanchese. “We’ve done a lot of work around this area both on the front side and the back side of the island.”

Supporter Spotlight

Corbett said he’s not the only one thinking about it, so is the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “This is a real interest to Fish and Wildlife given their management of the area.”

Natural barrier island processes do not suddenly stop at the boundary of the wildlife refuge.

The north end of Rodanthe, the Mirlo Beach subdivision, is subject to regular ocean inundation. The southern terminus of the new bridge will be a traffic circle about three-quarters of a mile south of Pea Island. When the bridge opens to traffic, that section of the road through Mirlo Beach will no longer be a primary highway, although NCDOT says it will continue to maintain it.

“Division 1 intends to maintain access along this remnant portion of NC 12 as we do other secondary routes in Dare County and the State by clearing sand, water, snow and ice and other debris as conditions warrant and are safe,” Tim Hass, communications officer with NCDOT, responded this week to Coastal Review in an email.

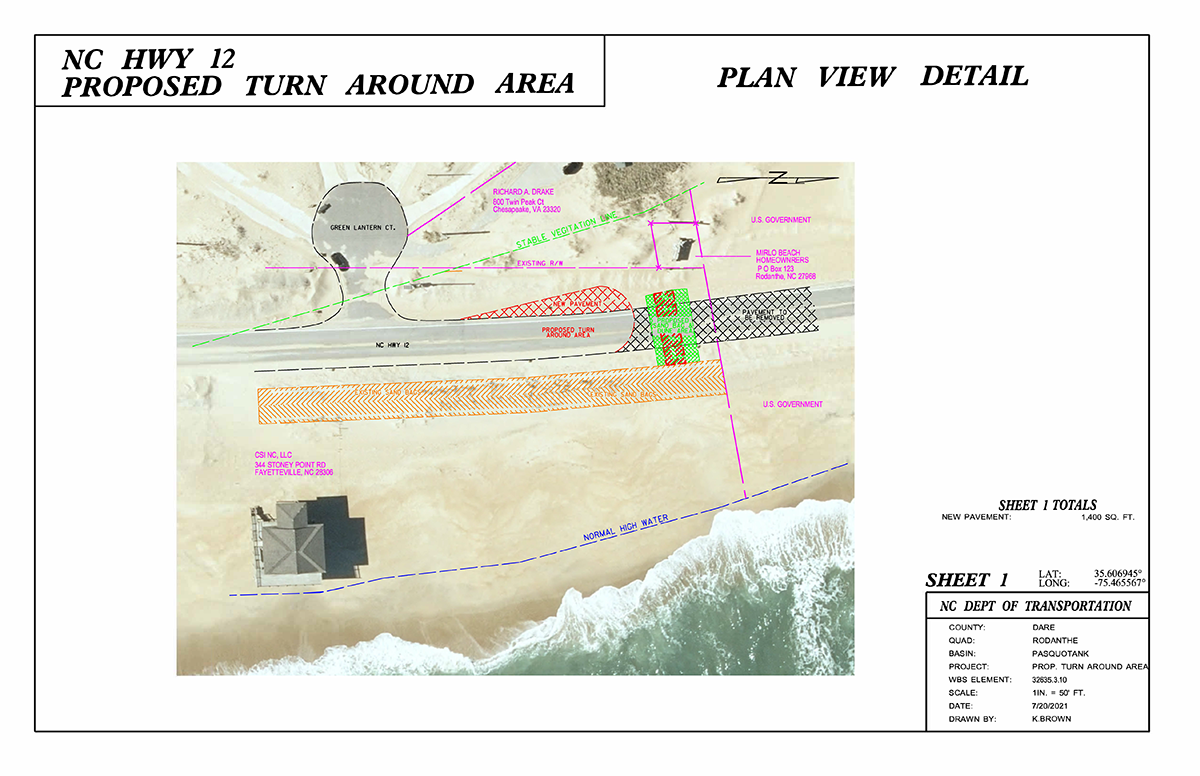

Currently, NCDOT has sandbags placed parallel to the road south of the refuge, and the department is planning to extend that protection to a turnaround area, although they do not yet have a permit to do so.

“NCDOT applied for a permit from the NC Division of Coastal Management to install sandbags and a modified cul-de-sac at the north end of the remnant portion of NC 12,” Hass wrote in the email. “The permit application was not approved by (the N.C. Division of Coastal Management). The NCDOT has appealed the permit application decision by NC-DCM to the Coastal Resource Commission.”

The department’s request for a variance is on the agenda for the commission’s meeting Feb. 9-10 in Beaufort.

The department seeks commission approval for about 50 feet of sandbags at the end of the modified cul-de-sac that would be placed perpendicular to existing N.C. 12.

The area including Mirlo Beach is subject to frequent ocean overwash, and at times seawater will reach the sound, but it remains unclear exactly what will happen here over time.

Corbett, with the Coastal Studies Institute, described the breach that Hurricane Irene created just a mile and a half north of the area — where the Richard Etheridge Bridge is now — as a model for what may occur.

After Hurricane Irene passed in late August 2011, an inlet formed here and cut off highway access. The inlet was as much as 30 feet deep and 100 to 150 feet across then, and Corbett noted that it was a first for NCDOT in that when N.C. 12 was breached, the department did not try to fill in the inlet, choosing to bridge the gap instead.

But over time, sand naturally accreted in the breach, filling it in. The area is now a wide, fairly flat swath of sand between the ocean and Pamlico Sound.

“That showed a natural progression of what the island did when the natural processes were allowed,” Corbett said.

Although there are similarities between the New Inlet breach, as it is known, and the shoreline closer to the jug-handle bridge, there are also important differences.

“One of the things that’s different in that (the S-curves) location, new New Inlet had these, for lack of a better word, a canal or a creek that sort of moved from the sound side very close to the road. And those already had some depth to them,” Corbett said.

The area that the jug-handle bridge is bypassing does not have those deep canals or creeks on the sound side. That was apparent after Irene overwashed the area. When water from the Atlantic flowed into the sound, instead of a single deep breach between ocean and sound, there was a series of narrow, shallow creeks.

The researchers said changes in the area will be dynamic.

“I think we’re likely to see significant overwash and it may be a breach,” Corbett said.

But what is uncertain is how tenuous or permanent the connection between the ocean and sound will be.

“You have this very broad very shallow sand flat on the backside and there’s no real depth … a creek or anything that really comes up close to the road,” he said. “I’ve been out there, and I’ve collected some bathymetry. I was surprised at how shallow it is throughout that very broad region, without really any cuts in that, like a canal or a creek, moving up into the barrier.”

He also found a significant amount of sand in the water, leading him to wonder if it is an area that would be prone to inlet formation.

“Can we somehow move water in such a way that does breach this region, given the amount of sand that we have on the backside of the island right there?” he theorized. “Or would we see a breach someplace else first? As soon as you breach the island at some place, it sort of acts as, releasing the cork. So, if you create a breach someplace else first, you don’t have the same pressure on the system at any other location.”

Related: Bridge will bypass Pea Island, but refuge access to remain

When a breach or an inlet forms, a limiting factor on whether the rift is permanent or transitory is the amount of freshwater from mainland rivers that is flowing into the sounds of the region, and that, too, becomes a limiting factor.

“Because of the amount of fresh water, our tidal exchange system can likely only handle a certain number of inlets,” Corbett said. “It’s sort of an interesting line of potential study — understanding our inlets and our flow — to better understand what it might look like in the future.”

The one factor though, the single most dynamic event that is also the most unpredictable, in determining what will happen in the S-curve area is coastal storms.

“If you can tell me when we’re going to get storms and what storms and where they would go, I could tell you exactly what would happen,” Riggs with ECU said. “If we have the right storm, it will open. It will open as an inlet, but it won’t stay open.”

Such inlets are ephemeral, he added.