Coastal Review features the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who studies the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state’s coast as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.

A little more than a century ago, a group of seagoing people from the “Down East” part of Carteret County, settled on the shores of Lake Erie and began commercial fishing.

Supporter Spotlight

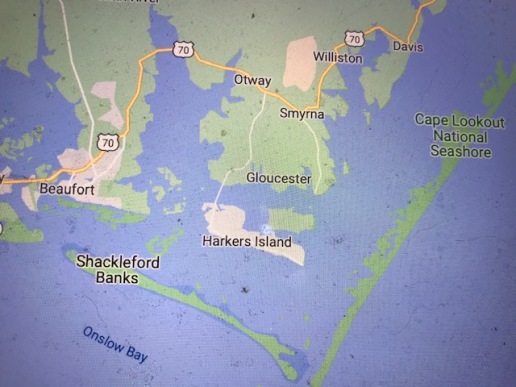

They came from a part of Down East known as the Straits, five miles east of Beaufort. At that time, it was a quiet, remote land, hundreds of miles from the crowds and clutter of Industrial America. The local people largely got around by boat. Salt marshes and broad estuaries stretched to the horizon.

But of course the sea has no boundaries and the world’s oceans and rivers make neighbors of us all.

So it was with the people from the Straits. They followed the sea a thousand miles from home and built a community that was a tiny piece of Down East on the shores of Lake Erie.

A trip to Vermilion

The story of those Down Easterners on Lake Erie has never really been told. I only learned about them recently myself. As best I can tell, all but a few old timers have forgotten them.

But recently my wife and I happened to be vacationing at two dear friends’ cottage in Vermilion, Ohio, right on Lake Erie, which is one of the places that those Down Easterners made a new home.

Supporter Spotlight

As soon as I got to Vermilion, I recalled that one of the grandchildren of those wandering Down Easterners got in contact with me a year or two ago and told me their story.

That man’s name is Giles Willis Jr. Now 88 years old, Mr. Willis spent much of his early life on Lake Erie. He shared photographs of those days with me, and he told me stories about his life there when he was a boy. He recalled as well what his father and other older relatives had told him about their fishing days on Lake Erie before he was born in 1932.

He also sent me a video copy of a wonderful interview with his father’s sister Evelyn describing the little community on Lake Erie.

Love on Lake Erie

According to Mr. Willis, the first fishermen from Carteret County to settle on Lake Erie were his great-uncle Giles Whitehurst and another man named Tom Pigott.

Whitehurst and Pigott were both from the Straits and had always been around boats and water people. In the late 1800s, Giles Whitehurst’s father, Capt. John A. Whitehurst, had been the master of a three-masted schooner that traded all along the East Coast and in the West Indies.

His last vessel, a two-masted schooner named the J. H. Potter, was built at North River, not far from the Straits, in 1875.

Capt. John A. Whitehurst eventually bought farmland in the part of Straits that came to be called Gloucester in the early 1900s. The village was named after the Massachusetts seaport that another local schooner captain used to visit on his voyages north.

Capt. Whitehurst’s son Giles Whitehurst and the captain’s old first mate, Tom Pigott, apparently set out on their own to make a living on the water in the last years of the 1800s or in the first few years of the 1900s.

For a time — I’ve heard secondhand — they may have fished down in Punta Gorda, Florida, where another, larger group of Down East fishermen had gone in search of new fishing grounds in the late 1800s.

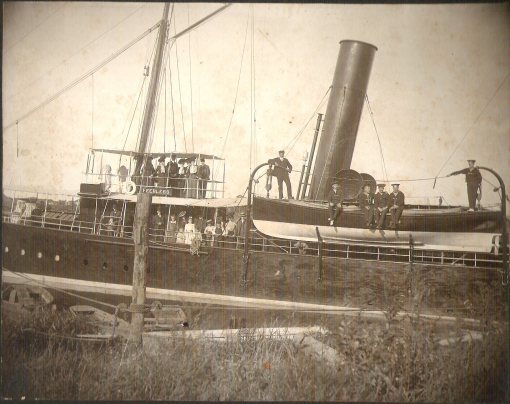

Pigott and Whitehurst later ended up far to the north though. They may have worked on a number of vessels, but Giles Willis, Jr. recalled one in particular, a steam yacht called the Peerless. Tom Pigott was apparently the yacht’s captain and Giles Whitehurst was his first mate or engineer.

Eventually their voyages led them to Lake Erie. There, on the south shore of the lake, in the town of Grand River, Ohio, Giles Whitehurst and Tom Pigott met a pair of sisters and fell in love.

Giles Whitehurst married Adah Searle in 1906. Tom Pigott married her sister Mabel around the same time.

A fishery at Grand River

According to family lore, Giles Whitehurst was the first of three Whitehurst brothers to fish on Lake Erie. Another brother, Richard, soon joined Giles in Grand River. In or about 1915, the brothers opened a fishing business there.

Richard Whitehurst met his wife in Grand River, too. Her name was Olive Swan and she was from Iowa.

Yet another brother, Monroe, joined them after he finished a stint in the U.S. Life-Saving Service during World War I.

Giles Willis Jr.’s father, Giles Willis, was one of a number of other Down Easterners who joined them in the mid-1920s. He was the son of the Whitehurst brothers’ sister, Olivia, and Wilbur Willis, who was from Williston, a village 6 or 7 miles north of the Straits.

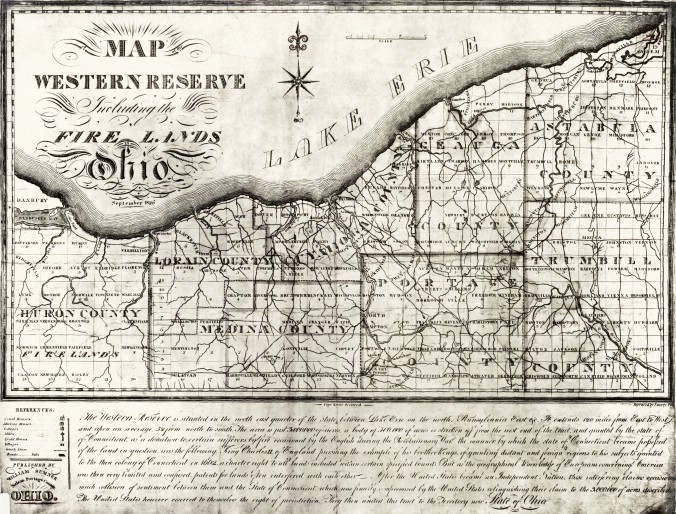

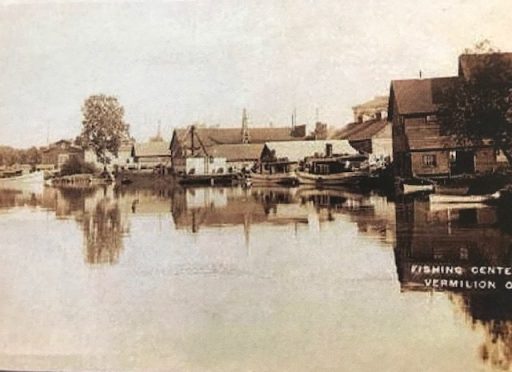

Then, sometime around 1930, the Whitehurst clan left Grand River and relocated to Vermilion, 70 miles to the west, on the other side of Cleveland. The town is situated at the mouth of the Vermilion River, where it flows into Lake Erie, in what people up there used to call “The Firelands” or the “Sufferers’ Lands.”

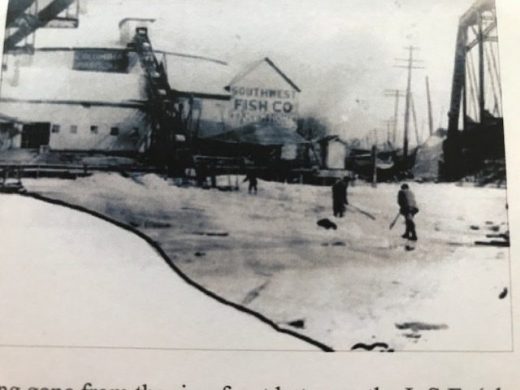

At that time, Vermilion probably reminded the Whitehursts at least a little bit of home. Fish houses lined the waterfront. Fishing boats crowded the little harbor. All along the shore, nets were spread out to dry. Almost every family made their living by fishing.

Of course, not everything was the same: winters were snowy and icy and the little town was beset by storms that sometimes came off the lake with bone-chilling fury.

At the Vermlion History Museum and the Ritter Public Library in Vermilion, I found historical photographs of fishing boats with so much ice on them that I can’t imagine how they stayed afloat.

Many a winter, at least early on, the Whitehursts left Lake Erie and came back south to fish in warmer waters until the spring.

A Vermilion fishing life

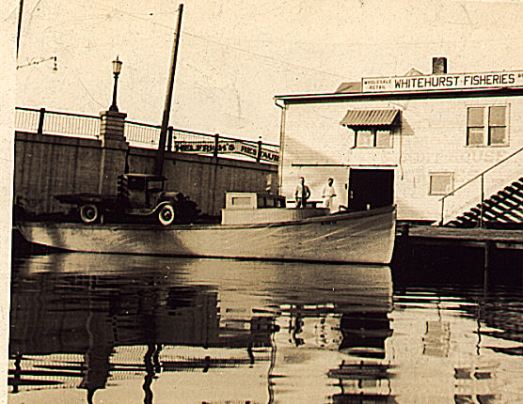

When they settled in Vermilion, the Whitehursts operated three boats, all of which Giles Whitehurst built himself.

He ran one of the boats. He and his brothers had recruited two other fishermen from Carteret County to captain the other two.

While Giles Whitehurst oversaw the family’s fishing operation, his brother Richard ran their wholesale fish business and their brother Monroe, known as “Mund,” ran their family’s retail fish market, which was located on the second floor of the family’s fish house.

On the day I talked with him, Giles Willis Jr. remembered how, when he was a small boy, his great-uncle Richard would take him down to Lake Erie around 3 in the afternoon and they would look for the boats coming back from the fishing grounds.

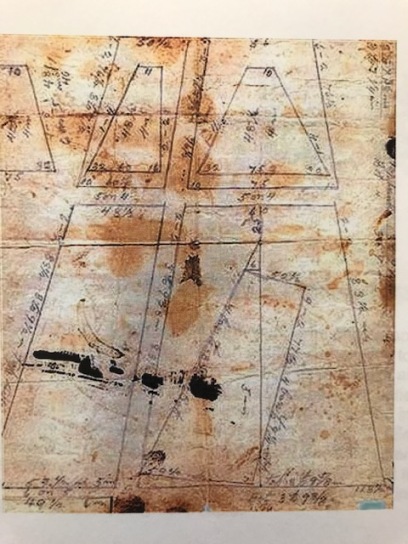

The fishermen tended trap nets, which they staked out on the lake bottom as soon as the ice broke up in the spring. (You can see a yellowed, stained example of a Vermilion fish company’s trap net plan from that era in the illustration below.)

In that weather, they required sturdy, covered boats that the Lake Erie fishermen called “fishing tugs.”

When I talked with Giles Willis Jr., he recalled how the fishermen dumped their catches out on the dock when they got back from the fishing grounds. The Whitehursts and the other workers, most were from Carteret County, would then sort them.

In those days, he said, they caught a lot of blue pike, white perch and pickerel (walleye) — the last being, he said, “a big fish.” He remembered that his dad often catered fish fries in Vermilion and the white perch were especially in demand at those events.

He recalled that roughly 10 people were working in the fish house when the boats unloaded at the dock. Each of the three boats had two or three crewmen. “The ones from Carteret County were staying upstairs,” on the second floor of the fish house, he told me.

After Giles Whitehurst died of pneumonia in 1933, his brother Monroe took over the boats and Giles Willis Jr.’s father started a fish market that was located separate from family’s fish house.

They also did a good deal of wholesale business. When the boats came in, they put the fish into boxes with ice in them, nailed them shut and put them on a truck. They carried them to the local train station and put them on a train for shipment to Cleveland and other distant parts.

Giles Willis Jr. told me that he loved going out on the fish house dock and watching the trains cross the Vermilion River on the New York Central Railroad Line. The freight trains were fun to see, too, but he especially liked to watch the 20th Century Limited, the famous all-silver express train that ran from New York to Chicago.

“That would be a time — a little kid is going to look at this train and wonder who’s on that train and where they were going and (dream) maybe one day I would get to ride that train … ”

Coming Home

The little enclave of Down Easterners stayed on Lake Erie a total of roughly 40 years. The Whitehursts sold their fish business and moved back home to Carteret County in 1948.

I am not sure exactly why the Whitehursts and the other Carteret County fishermen left Lake Erie.

But when I visited the Ritter Public Library and the Vermilion History Museum, I learned that 1948 was around the time when commercial fishing catches on Lake Erie plummeted and Vermilion’s fishing boom ended. Today you won’t find a fish house in the town and there is very little commercial fishing on that part of Lake Erie.

Giles Willis Jr. estimated that somewhere between 30 and 40 Down Easterners made their home on Lake Erie over the years. Some stayed all year, while others traveled back and forth seasonally between the big lake and fishing grounds back south.

Those were not easy years for Carteret County’s fishermen. Especially during the Great Depression, many left home and followed the sea wherever it led. Some went looking for new fishing grounds. Some went in search of dredging, piloting and other maritime work anywhere they could find it.

In those days, if you lived on the North Carolina coast, it sometimes felt as if the local fishermen had scattered to the four winds. In New York City, for instance, every harbor pilot seemed to come from Smyrna, a village a few miles from Straits. On Ocracoke Island, on the other hand, every family seemed to have a father and/or a few sons that had left home and gone to work on dredge boats in Philadelphia and the Delaware River.

You can find my story on the historical connections between Ocracoke Island and Philadelphia here.

Florida was another place where Down East fishermen often strayed. Along the shores of the Straits and its neighbors — Harkers Island, Otway, Marshallberg — every family seemed to have somebody in Florida for at least part of the year, shrimping in Punta Gorda, for instance, or mullet fishing in Cortez, or menhaden fishing in Fernandina Beach.

Back in those days, travelers often described the Down East part of Carteret County as a remote land, where the “simple fishing people” remained untouched by the outside world. They seemed to think that everybody was descended from old English settlers, and they declared that the local people had little knowledge of the bigger world and its ways.

But none of those things was true at all, and such descriptions of any part of the North Carolina coast were and still are merely fanciful. As Giles Willis Jr., who is nearing his 90th year, told me, “There’s always been a lot of back and forth between Carteret County and Ohio.”

Mr. Willis no doubt knows too, as I have learned, that Ohio is only one of many, many such places where those quiet little villages Down East are tied to distant lands by the sea.

* * *

Many, many thanks to Dennis Chadwick, Roger Whitehurst and most especially Giles Willis Jr. for all their help with this story. Thanks, too, to the staff and volunteers at the Vermilion History Museum, the Ritter Public Library in Vermilion and the Core Sound Waterfowl Museum & Heritage Center on Harkers Island. Finally, a big shout out and deep gratitude to Paul Baldasare and Jane Wettach for sharing their cottage in Vermilion with my wife Laura and me. One could not ask for a nicer place to stay or better company.