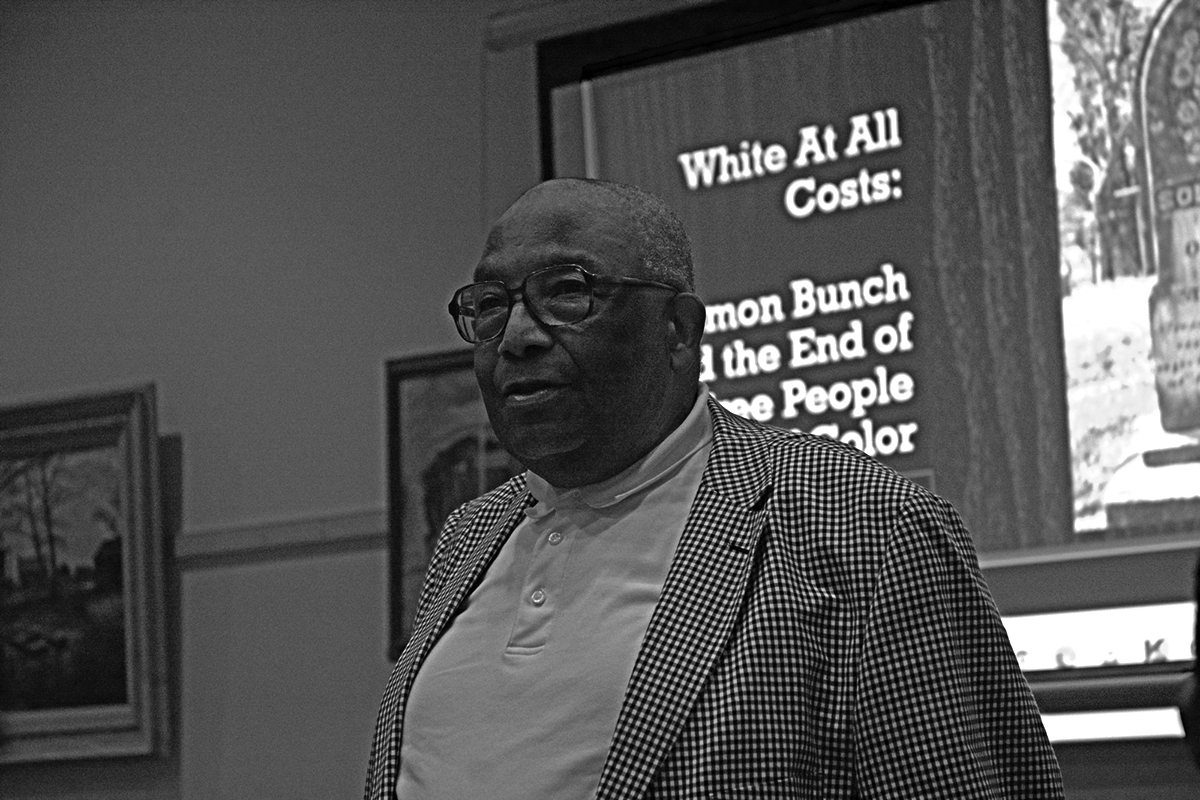

Dr. Ben Speller, a retired professor and dean of the School of Library and Information Sciences at North Carolina Central University, left his family’s farm in Bertie County in the 1950s, but his journey eventually led back to his childhood home where he stays active in the community.

That journey includes a history degree from what is now North Carolina Central University but was known as North Carolina College when he attended. He earned a master’s in library science and a doctorate in management information systems, both from the University of Indiana. And he has worked for the state and the federal governments. His work has been credited as inspiring the creation of the state’s African American Heritage Commission.

Supporter Spotlight

Having retired in 2003, Speller serves on the board of directors for the Roanoke Island Historical Association, the nonprofit group that produces “The Lost Colony” outdoor drama. He is secretary of the Edenton Historical Commission and board vice president with Bertie County Hope Plantation.

“The reason why I’m in a lot of different places is because I believe in collaboration. I try to see the opportunities in different places to develop what the communities need,” Speller recently told Coastal Review.

His range of interests includes everything from the intricacies of government budgeting processes to his multi-racial heritage and the state of race relations today. Cheerful, outgoing and friendly, his observations are often delivered with a smile and a bit of laughter but also with the seriousness of a history scholar and archivist when discussing present-day problems that are deeply rooted in the nation’s past.

Race relations throughout history and race itself aren’t always as clear as black and white, Speller has learned.

“I’m from a mixed-race family. I have family members that — generally I’m talking about my white ones — that don’t want anybody to know that they have any Black relatives,” Speller said.

Supporter Spotlight

Speller was born in Bertie County in 1940.

“I grew up on my grandfather’s farm,” Speller said. “His father was an only child, which is quite unusual for an African American family. I don’t know how he got his economic situation, but I would say he was middle class. I mean, he had more economic resources than most African Americans of that time.”

Those resources factored in during his grade-school education that was spent entirely in segregated schools. Although school funding and supplies were often lacking, the level of instruction and quality of teachers were on a par with the white schools, he said.

There was the chemistry teacher with a degree in chemistry who was also a coach at the school, but as his coaching duties took over, the home economics teacher filled in as chemistry teacher.

“She was really better than he was. She later went to medical school,” Speller said.

Speller’s grandfather, however, felt more was needed.

“My grandfather … he had a classical curriculum and he thought that we (Speller and his brother and sister) should have it too,” he recalled. “When we got to a certain age, they didn’t have German, and he thought we should have German and I went to Philadelphia during the summer and took German at one of the year-round schools there.”

After high school, Speller’s education continued at what is now North Carolina Central University, a historically Black university in Durham. At that time, N.C. Central was called North Carolina College at Durham.

Speller was a history major and in 1961, after only three years, was close to completing his degree requirements. He needed two more courses but those were offered only at nearby Duke University, which wouldn’t admit its first Black undergraduates for another two years.

On Speller’s behalf, North Carolina College President Alfonso Elder spoke with Duke University’s president.

“They ended up wanting me to take some courses in the history department, but the history department did not want to accept a Black (person) at that time,” Speller said. “So, I ended up finding two courses in colonization of Africa in the department of history in the (university’s) school of religion.”

Speller said those two courses were essential to his understanding of the role of race, religion and politics in the world.

“That opportunity gave me a different perspective on looking at the colonization of this country, and also the current and past caste system that we have,” Speller said. “It made me realize that most of what was going on was really for economic reasons. You could really see what was going on. Even though the missionaries were there to proselytize, it appears that they were they are also for economic reasons.”

This kind of perspective has become especially controversial in terms of America’s history. The term critical race theory has evoked fiery passion during the past year, especially among those who most adamantly oppose the concept without a clear grasp of its meaning.

The American Bar Association defines critical race theory as a practice that emerged among legal scholars that examines how race and institutionalized racism created and perpetuates a system that relegates people of color to the lowest tiers of society.

For Speller, critical race theory is not an academic construct — it’s just reality.

“When somebody talks about critical race theory, I say, ‘We didn’t have to deal with critical race theory, we knew exactly what it was.’ It was a fact, it wasn’t a theory,” he said.

Speller has extensively researched his family’s history and that of other families and concluded that economic and social divisions are clear even where racial lines may be blurred.

Speller’s family research goes back to the 1640s and has turned up family connections that in some cases were never acknowledged. Links include a former North Carolina governor and a number of prominent white families.

“I have a whole slew of family members that have mixed race, but they were never slaves. I mean, a whole bunch of white mothers,” he said. “The ones I know claim they are white or believe they are, but there may be some mixed blood in there.”

His paternal grandmother was named Outlaw, and her father was of mixed heritage, “and his father was one of the Outlaw sons of one of the large plantation owners of Bertie County,” Speller said.

The Outlaw surname was what sparked Speller’s family research. He had been contacted by a woman from Texas who was an Outlaw descendant, and she was looking for a family church that had been in either Chowan or Bertie County. She told him that as she was researching her family tree, she discovered Speller’s family seemed to be connected.

“She said, ‘Whatever I find here, I’ll send to you. We are almost identical, in the same situation.’ And then I took it from there and went back to the assessor’s records and all of the records back to the 1640s and got it together.”

Along the way he relied on public records and genetic testing as research tools, but there was at least one other trusted source of information.

“The females know (family histories) better than the males. Every time we do editing of our history books on Bertie (County), … they tell everything. I found out that the white females in the area know more about the history of these situations than the men think they do,” he said.