According to his family’ papers at the Greensboro History Museum, the photographer Charles Farrell visited the Varnamtown fishermen at Bald Head Island in the fall of 1938.

At the time, he was staying in Southport, where he was photographing commercial fishermen and women mainly in the town’s two largest fisheries, the menhaden industry and the shrimp industry.

Supporter Spotlight

However, one day he also accepted an invitation to join a boating excursion across the Cape Fear River to Bald Head Island.

Today Bald Head Island is home to a sprawling beach resort, as well as a lovely wildlife preserve. At that time, though, the island was uninhabited, except for the likes of wild hogs and goats.

The wild hogs and goats roamed the island’s palmetto groves and live oak forests, looking askance no doubt at the fishermen, hunters and beachgoers that occasionally showed up.

Farrell did not expect to find commercial fishermen on the island that day. However, when he and his group arrived on the island, he discovered a crew of mullet fishermen at work. They were fishing on the ocean beach, not the river side of the island, quite likely on the same stretch of seashore and in much the same way as their families had been doing for generations.

(Mullet crews tended to be territorial, to say the least, and one did not tread on another crew’s beach lightly. Once a clan of fishermen claimed a beach, they often kept it for generations.)

Supporter Spotlight

Better known locally as “jumping mullet” or “bug-eye mullet” (for obvious reasons when you get to know them), striped mullet made up one of the most important saltwater fisheries on the North Carolina coast all the way from the late 1700s to World War II.

That was due partly to the incredible abundance of striped mullet in the waters just offshore the state’s barrier islands, particularly between Cape Lookout and the South Carolina border.

The striped mullet fishery also flourished because the fish take so well to being preserved with salt. Salting was the only method for preserving fish that was used extensively on the North Carolina coast prior to the introduction of mechanical ice making and refrigeration.

Particularly in the late 1800s and early 1900s, North Carolina’s fish dealers shipped vast quantities of salt mullet across the Eastern Seaboard. Kegs of salt mullet were also a staple in local pantries and winter storehouses.

On Bald Head Island, Farrell learned that the mullet fishing crew there came from Varnamtown, a fishing village 12 miles to the west in the tidal waters of the Lockwood Folly River.

Most — and maybe all — of the mullet fishermen at Bald Head Island that day were members of the Varnam clan — if not Varnams, they were likely cousins by marriage or other distant relatives.

The Varnams were a tough lot, by reputation, and some of the best known fishermen, vessel captains and boatbuilders on that part of the coast.

Like so many of the old fishing families, the Varnams (sometimes spelled “Varnums”) came to the North Carolina coast from a maritime part of New England. In their case, Sagadahoc County, Maine. The first Varnam settled on the banks of the Lockwood Folly River not long before the Civil War.

The first Varnam to come south, Roland Varnam, is said to have met a Native American woman, Sarah Jane Pridgen, when he arrived. The couple married and settled down by the shore and raised a family.

Over the generations, the Varnams stuck to the water: fishing, carrying freight and going to sea. Even into the early 1900s, the Varnams were building wooden sailing vessels, some of them for fishing and others for hauling freight between the little villages of Brunswick County and Wilmington.

As late as 1900, Capt. W. H. Varnam built a 37-foot coasting schooner, the Lillie V. Three years later, Harry Varnam and Roland Varnam (perhaps the first local Varnam’s grandson), along with John Holden, built and launched a new sharpie, the H. and V. Royall.

I wish I knew who the specific fishermen in Farrell’s photographs were and something about more about them.

I have only a couple of guesses. One might have been Wesley B. Varnam, who had once been the keeper of “Old Baldy,” the Bald Head Island Lighthouse, and knew the island especially well.

Another was almost certainly Johnny Varnum. I only know about him because he was a central figure in both a notorious double murder and a storied rescue of drowning swimmers.

In May of 1932, Varnum apparently discovered that his wife was having an affair with another man. He shot and killed his wife, then killed the other man. He then tried, unsuccessfully, to kill himself. He finally turned himself in to the local sheriff and was later given a 20-year sentence for manslaughter.

In August 1937, however, Johnny Varnum was part of a prison work detail somewhere below Southport, presumably on Oak Island. The job of the prisoners on the work detail was to catch and salt fish for the consumption of the state’s inmates.

While they were fishing there, a group of visitors from High Point were cast fishing in heavy surf nearby. A wave apparently knocked down a young boy, and a riptide quickly pulled him over his head. Seeing the boy in trouble, his mother and father and another woman went in after him, but all were soon panicking and in danger of drowning.

On hearing their cries, Johnny Varnum came to the rescue. Rushing to the scene, he organized a chain of inmates from the shore into the breakers, with himself at the end of the chain reaching the four people in trouble and carrying them to safety.

A year later, in September 1938, Johnny Varnum was given a full pardon and released from prison after only serving six years of his sentence. According to W. B. Keziah, the Southport Leader’s editor, he immediate joined his kindred from Varnamtown at the mullet fishery on Bald Head Island.

I don’t know which of the men in these photographs is Johnny Varnum, but he should have been there when Farrell visited the island.

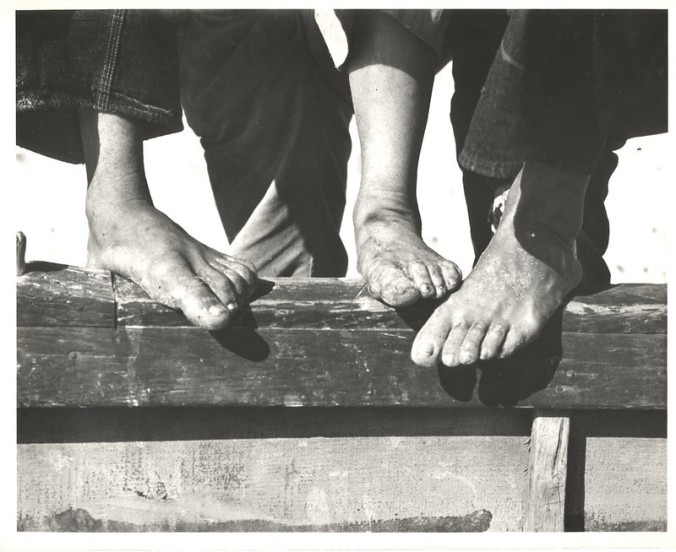

This was still the Great Depression and we can tell that the gang of fishermen from Varnamtown was a threadbare lot. Note the shoeless, worn feet, the old, sun-bleached trousers and shirts and the one older fisherman sitting next to the handsome young man in the straw hat that used little wooden pegs to hold together his shirt, almost like toothpicks, instead of buying buttons.

In the 1930s, nobody was making much money commercial fishing on the North Carolina coast, but the Varnamtown fishermen kept busy all year and seemed to be on the water all the time.

They fished for mullet on Bald Head Island in the fall. They joined Southport’s shrimping fleet when the shrimp were running, and they harvested oysters in the Lockwood Folly River in cold weather. When there wasn’t anything else to do, they retreated to their boatyards and fish houses, their duck blinds and hunting camps and the warmth of home and hearth.