Coastal Review is featuring the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state’s coast as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.

In the late 1930s, a photographer named Charles A. Farrell documented fishing communities across the North Carolina coast. In this post, I’d like to look at one group of those photographs, a collection of images of the menhaden industry in Beaufort and Southport.

Supporter Spotlight

By the time that Farrell took these photographs, the menhaden industry had been the state’s largest saltwater fishery for more than a generation. Locally known as “shad” or “pogie,” the silvery little fish were the basis of a huge commercial fishery that was the second industrial fishery in the U.S., after whaling, when it first developed in New England in the early 19th century.

Here in North Carolina, the centers of the menhaden industry were Beaufort, Morehead City and Southport. On their waterfronts, menhaden boats lined the wharves and factories processed tens of millions of tons of fish annually into massive quantities of fertilizer and oil.

When the wind was right, the aroma of the fish covered those towns like a blanket. Coastal visitors sometimes complained, but my cousins in the industry used to call it “the smell of money.”

The menhaden industry flourished on the North Carolina coast for more than a century. However, the state’s last menhaden factory, Beaufort Fisheries, closed its doors in 2005.

Over the last few years, when I am in these old fishing ports, I have occasionally carried Farrell’s photographs to old timers who used to work in the menhaden industry. We have looked at them together and talked about what they see in them, the people and the places and a way of life that is no more.

Supporter Spotlight

In this post, I would like to share a little of what I learned from a few of those old timers about the world of menhaden fishing in those long ago days before the Second World War.

* * *

When I was in Southport several years ago, I carried Farrell’s photographs to an old menhaden fisherman named Charles “Pete” Joyner. At the time, Mr. Joyner was 93 years old. He has since passed.

The photograph we started with was this portrait of a fisherman on the deck of a menhaden boat in 1939. Farrell took more than a thousand photographs on the North Carolina coast, but this is one of my favorites.

Sitting in his living room, Mr. Joyner smiled broadly when he saw the man’s face. He and the fisherman in Farrell’s photograph had been neighbors in Southport when he was a boy. They were cousins, too, and nearly 80 years ago they had been crew mates on a menhaden boat for a time.

The fisherman’s name was Elias “Nehi” Gore. In Farrell’s photograph, he is standing on the deck of one of the Brunswick Navigation Co.’s menhaden boats, the W.A. Anderson, John D. Eriksen, captain. He is resting one arm on one of the Anderson’s two purse boats.

Gore was a legend. In those days before power blocks and hydraulic lifts made menhaden fishing rely less on brute strength, most of the fishermen tended to be big, strong men. Elias Gore was the biggest, though, and he was reputedly one of the strongest.

He was at least 7 feet, 8 inches, in height, and as we can see in Farrell’s portrait of him, he was not slight of build.

He was born in Southport, a village at the mouth of the Cape Fear River, in 1906. He lived just down the street from from Mr. Joyner, who recalled that the big fisherman was the oldest or one of the oldest of 11 children.

Gore began working on menhaden boats when he was just a boy, he said. He had left school young and looked to menhaden fishing as a way to help his family get through hard times.

Another former Southport fisherman, Tookie Potter, whose father was a local menhaden boat captain, remembered that the menhaden company always paid Gore double wages because he was worth two good men on a boat. Those wages sent two of Gore’s younger siblings to college, not an easy thing to do in those days.

Pete Joyner and Elias Gore had worked together one fall, on a Southport menhaden boat that had gone up to Beaufort in pursuit of the big roe menhaden. That was not long after Mr. Joyner first went menhaden fishing in 1939. He was 17 years old at the time.

He told me that Gore was known for his gentleness and even temper, his devotion to his family and for his tenderheartedness.

“He was a good man to be around,” he said.

Mr. Joyner recalled that he had often seen Gore stop fights simply by picking up two men by the scruff of their necks, one in each hand, and holding them in the air until they calmed down.

Gore passed away in 1944, at the age of 38. An early death seems to have been the fate of many men of his size in those days, no matter the size of their hearts.

Farrell’s photograph is the best-known portrait of Elias Gore. Back in 2013, the North Carolina Maritime Museum Southport even used a life-size version of the photograph in an exhibit dedicated to his memory.

I think I like Farrell’s portrait so much because he captured Gore’s strength and size, but also the quiet dignity and gentleness within him.

* * *

On a trip to another part of the North Carolina coast, I was very fortunate to have the opportunity to share Charles Farrell’s photographs of the menhaden industry with Capt. David Willis, one of the longest-serving menhaden boat captains in the United States.

I visited Capt. Willis in his hometown, Beaufort just down the road from where I grew up. At that time, he had just marked the 50thanniversary of being a menhaden boat captain.

Capt. Willis had first taken command of a menhaden boat when he was only 24 years old. When I visited with him, he was 74 years old and still the captain of a menhaden boat.

He grew up in Lennoxville, a neighborhood in Beaufort that many of the old menhaden boat captains used to call home.

He dropped out of school in the 10th grade to go fishing. It was a family tradition. His father had been captain of a menhaden boat. His grandfather had been captain of a menhaden boat.

His great-grandfather was menhaden fishermen, too. But back in those days, most menhaden fishing was done from the shore with nets, not from boats, at least in the fishing villages and islands near Beaufort.

Capt. Willis has always lived in Beaufort. However, he has worked on menhaden boats as far away as the Gulf of Mexico. We talked in Beaufort, just after he had finished a season of menhaden fishing in Moss Point, Mississippi.

One of the first of Farrell’s photographs that caught his eye was this image (above) of fishermen relaxing on the stern of a menhaden boat called the W.A. Mace. It brought back a lot of memories for him. His father had once been captain of the Mace, though probably not at the time that Farrell took the photograph.

In the photograph, the Mace is docked at the Beaufort Fisheries wharf on Taylors Creek in Beaufort.

Taking in her lines (in other photographs), Capt. Willis estimated that the Mace had the capacity to hold approximately 550,000 fish. Menhaden boat captains liked to come home with a full boat, and in those days they often did.

Pointing to the fisherman on the boat’s stern, Capt. Willis mused, “Must be Saturday afternoon.” In those days, the fishermen worked six days a week on the boats, then got paid off on Saturday afternoon and got to relax until first light on Monday morning.

Capt. Willis said this fisherman might have been living on the boat during the fishing season if he wasn’t from Beaufort. “He had a bunk and three meals a day,” he observed, and that was nothing to laugh at during the Great Depression.

Behind the fisherman, we can see a water barrel and quite a few bags of salt, Capt. Willis pointed out. The menhaden factory, where the fish were processed into fertilizer and oil, was just at the other end of the dock, and it had a “salt house,” he said.

At the end of every day of fishing, the fishermen soaked their nets in salt. “Pickling the nets,” it was called. The salt “killed off the slime,” Capt. Willis told me.

Another fisherman, King Davis, who you’ll meet below, told me that the salt also kept the nets supple and kept them from tearing and shredding the fisherman’s hands so bad, which was one of the banes of working in the nets in those days.

The salt came in 100-pound bags. The size of the bags led Capt. Willis to reminisce about a menhaden fisherman named Bill Neal, who was famous for showing off his strength by picking up a 100-pound bag of salt with his teeth.

The old cotton nets required a lot of care. Every menhaden company had its own “seine loft,” even if it was just on the dock, and a company’s net menders stayed busy. The boat’s crew did a lot of net mending too when they were fishing. Even after being tarred at the beginning of the fishing season, salted regularly and patched often, the old cotton nets generally only lasted a year or two, Capt. Willis told me.

At the time of this photograph, Capt. Willis explained, a captain didn’t necessarily need fishermen on his boat that could lift 100-pound bags of salt with their teeth, but “you had to have powerful, big strong men.”

That began to change at least some after the Second World War. In the 1950s and 1960s, menhaden companies adopted power blocks, hydraulic lifts and other machinery on their boats. With those innovations, boats began having smaller crews and the fishermen no longer needed to have the kind of weight-lifter strength that the fishermen had before the war.

(That doesn’t mean that there weren’t some big and powerful men working in the nets after the war, though: there were plenty.)

The story of Bill Neal and the salt bags reminded Capt. Willis of some of the other local menhaden fishermen that were famous for their strength. One stood out. Bill Neal was a strong man, he told me, but he couldn’t compete with a fisherman named James Henry.

“He could pick up the whole factory,” Capt. Willis said, and he didn’t look like he was joking when he said it.

* * *

* * *

On another trip to Beaufort, I visited with Ernest “King” Davis, a long-time first mate for Beaufort Fisheries. At the time, he was 74 years old and retired, but he had worked on menhaden boats for 44 years.

Davis hails from North River, an African American community a little north of Beaufort. He is from a family of menhaden fishermen.

He told me that he had first gone menhaden fishing on his father’s boat when he was 15 years old. Over the decades, he became one of the most respected first mates in the menhaden industry.

Farrell took these photographs in 1938 or 1939. Davis wasn’t even born yet then, but he thought he recognized some of the fishermen in Farrell’s photographs from his early days working on menhaden boats.

Davis wasn’t sure, but four of the menhaden fishermen in Farrell’s photographs looked familiar to him.

The first was Gene Stanley, who he thought might be the fisherman sitting on the stern of the Mace in the photograph above.

Davis recalled that, when he was growing in Beaufort, Stanley was the mate and later the captain of one of Beaufort Fisheries’ sound boats (as opposed to “ocean boats”). “He knew what he was doing,” he told me.

When Davis was young, Stanley was a deacon at Mt. Zion Missionary Baptist Church in Beaufort. He was, in Davis’s words, “well to do.” In addition to menhaden fishing, he owned a little grocery store and quite a few rental houses on Craven Street.

Davis told me that he wasn’t positive that the fisherman on the Mace’s stern was truly Stanley, but he immediately thought of Stanley when I showed him the photograph. “That’s where he typically sat and how he sat,” he remembered.

Davis thought that he also recognized three other menhaden fishermen in Farrell’s photographs of the W.A. Mace and its crew.

One of the men that Davis thought he recognized was Boot Dudley. He believed that Dudley was one of the men working the nets in one of the Mace’s purse boats in Farrell’s photographs of the fishermen in the waters off Beaufort. He looked so much younger in the 1930s than when Davis knew him that he could not be sure, but he thought it was him.

Dudley had been an important man in his life. When Davis had first gone menhaden fishing as a young man, Dudley had been one of his mentors, showing him the ropes and making sure he stayed out of trouble.

He said that Dudley and the other old timers at Beaufort Fisheries had worked him to the bone back then. “They were hard on me and they made me work,” he told me. He said he later appreciated it. “Those old men — they taught me well.”

Above all, he was grateful because they had taught him how to do the job safely. In all his years of menhaden fishing, Davis had never had a serious injury. He told me that he had not known many men in the industry that could say that.

Another fisherman that Davis thought that he recognized in Farrell’s photographs was Henry Bell. He believed Bell was “pulling net” in the mate’s boat (third from left in the photograph at the top of this section). “He was a good man,” he recalled. “Real quiet and would work.”

Davis said that Bell lived in Morehead City, on the other side of the Newport River from Beaufort. He remembered him attending St. Luke’s Missionary Baptist Church in Morehead.

The last man on the Mace that looked familiar to Davis was “Poppy” Frazier, who, judging from his last name, was from Craven Corner, a rural community 13 or 14 miles outside of Beaufort. A striking number of the town’s menhaden fishermen came from Craven Corner.

When Davis knew Frazier years later, he was the first mate on another of Beaufort Fisheries’ boats, the Taylor Creek.

“Them folk were strong people,” Davis told me, thinking about Frazier. “They liked to kill me.” He remembered Frazier being one of the strongest men in the industry. “He could pick up a 500-pound tom weight,” he said.

A “tom weight” is a heavy weight that menhaden fishermen toss overboard to close a purse seine. Attached to the seine with a heavy line, the tom weight functioned like the zipper on a woman’s purse, closing the net up with the fish inside—hence the names “purse boat” and “purse seine.”

Davis told me that a new fisherman was put “right on the cork,” but every man on a menhaden boat had to know his job and know it well or he’d put every other man in danger.

A big set of menhaden could be hundreds of thousands of fish. They might do anything. Perils were everywhere. Catching menhaden involved three boats — the big boat, or “mother boat,” and her two purse boats, and in those days a dozen men raising the purse seine out of the sea.

The fishermen had to work together. Every man had to know just what to do and when to do it. They were paid on shares and one wrong move and they could lose a week’s wages. Or somebody could get hurt bad.

As King Davis put it, “No time to play — if you didn’t know your job, you had to get a new job.”

* * *

Capt. David Willis, who we met earlier, spoke about menhaden fishing in much the same way. “It was a rhythm. It was like a ballet,” he insisted, smiling a little at himself for making the comparison.

This ballet had no conductor, however. When the fishermen were at work, neither the captain or first mate had time to tell the crew what to do or when to do it.

“There wasn’t time and there were too many contingencies — the weight of the fish, the wind, boat movements, a hundred things,” the captain said. The men drew on their own experience, and they used their own judgment.

To me he sounded a good deal like King Davis: “If you didn’t know your job, you didn’t get a job,” Capt. Willis stressed. “Everybody had his thing down pat.”

When Capt. Willis and I looked at Farrell’s photographs of the fishermen hauling in tons of of fish in a roiling sea, every man being pushed to his limit, each doing his job with astonishing precision and dexterity, I could see in his face how much he loved the excitement of it.

“When it worked right, boy was it fun!” Capt. Willis said, his eyes almost glowing, thinking no doubt of distant waters.

But then he added, perhaps thinking of a thousand mishaps and near disasters he had witnessed aboard his boats over the years, “But when everything goes wrong it’s no fun.”

* * *

A few months later, I was in Beaufort again. On this visit, I carried Charles Farrell’s photographs of menhaden fishing to Steve Goodwin, an amateur historian who I consider the foremost authority on the history of the menhaden industry in North Carolina.

Steve is an old friend and a person I always seek out when I want to understand more about the state’s menhaden industry.

He is from a local menhaden fishing family and worked on a menhaden boat summers when he was in college.

He never made a career out of menhaden fishing, but he has always been interested in the industry’s history. He has talked with many old timers, and he has done extensive research in archives and libraries around the U.S.

Steve is interested in every aspect of the menhaden industry’s history, so of course he was excited to see Farrell’s photographs.

The first of photograph that caught his attention was another photo of the menhaden boat W.A. Mace in Beaufort. In this photograph, we get a stern view of her at the Beaufort Fisheries dock on Taylors Creek 1938-39.

As soon as he saw the Mace, he immediately looked in a remarkable digital database that he has compiled on the state’s menhaden boats. He was quickly able to tell me that the W.A. Mace was built in the Meadows Shipyard in New Bern for the Atlantic Fishing Co. in 1925, but eventually ended up under the ownership of Beaufort Fisheries.

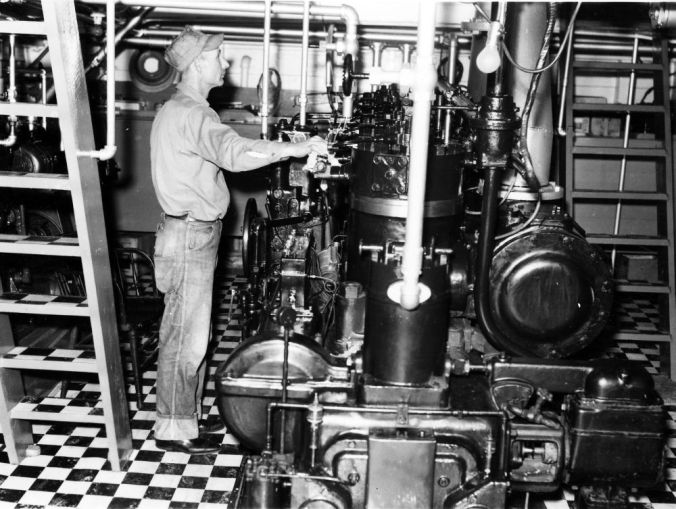

Steve’s records indicated that she was built mainly out of longleaf pine and white oak, was 87.1 feet in length and 30.3 feet in the beam and was powered by a 100 HP Fairbanks Morse single screw diesel engine.

She was named after one of Beaufort’s leading businessmen and civic leaders, William Arendell Mace. “Doc” Mace, as he was known, was president of both the Bank of Beaufort and one of the largest local menhaden companies, the Taylors Creek Fish and Oil Co., when they failed after the Stock Market Crash of 1929.

Mace was hardly unusual. I would not be surprised if every menhaden company in the state fail at some point during the Great Depression. In this case, another group of investors stepped in and bought the Taylors Creek Fish and Oil Co.’s assets and organized Beaufort Fisheries, the owner of the Mace at the time of this photograph, in 1933.

Steve and I then began looking closely at Farrell’s photograph of the Mace. On the left side of the photograph, he pointed to the net wheel. The Mace’s crew and menhaden factory’s hands used the wheel mostly for hanging the purse seines while they repaired them.

He also pointed to the bags of lime on the boat’s stern. They were used for “salting” or “pickling” the net. Beyond the salt bags, we can see barrels of drinking water, the purse boats on the boat’s starboard side, the davits for hoisting the purse boats and the hemp bumpers that kept the purse boats and the mother boat from chaffing when they rubbed up against one another.

Steve also walked me down the deck of the Mace. He pointed to the shelter over the boat’s engine room and, in front of the shelter, the boat’s hold, and then the pilothouse.

In the pilothouse, he said that you’d probably have found the officers’ bunks — the bunks for the captain, mate, engineer and pilot. Steve guessed that the Mace had its mess hall and crew quarters on the first deck, though some boats had crew bunks in the hull, rarely a comfortable place to bed.

Beyond the Mace, Steve pointed out a skiff, probably Harkers Island built by the look of her, with a man in the bow steering with his feet.

* * *

Back down in Southport, 100 miles south of Beaufort, I also shared Charles A. Farrell’s photographs of the menhaden industry with local historian Donnie Joyner.

Donnie is also also an old friend. He has been spearheading local efforts to highlight Southport’s African American history for years, and we’ve had several chances to work together.

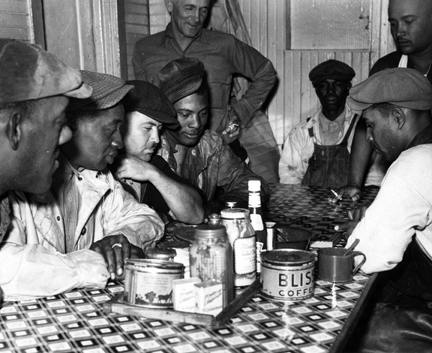

One photograph immediately snagged his attention. In that photograph (above), a group of fishermen are playing checkers at the mess table on the W. A. Anderson, one of the Brunswick Navigation Co.’s menhaden boats in Southport.

Donnie was especially excited to see the photograph because he recognized his uncle, Joe Reaves, as the last fisherman on the far side of the mess table.

With a little local research, Donnie later identified the rest of the fishermen at the table and called me with their names.

Thanks to Donnie, I now know that the fishermen at the table, from right, are Raphael Parker, Joseph Parker, Donnie’s uncle Joe Reaves, Frank Jackson and Elmer Davis and Elias “Nehi” Gore.

You will remember that Gore was the legendary, 7-foot., 8-inch tall fisherman that I introduced at the beginning of this story.

Behind the fishermen playing checkers, we can see the Anderson’s captain, John D. Eriksen.

A Norwegian immigrant, Eriksen came to the U.S. in 1906. He was nationalized as a U.S. citizen in 1916 and served in the American Expeditionary Forces in France during World War I. After the war, he returned home and went menhaden fishing.

Menhaden fisherman Charles “Pete” Joyner, whom I introduced earlier, recalled Capt. Eriksen as “quiet natured.”

In another of Farrell’s photographs, we can see the mess table on another menhaden boat, probably the W.A. Mace out of Beaufort. This time the fishermen are sitting down to a meal.

Time on a menhaden boat had its own rhythms, different than those on shore, and mealtimes were part of that rhythm. On “boat time,” breakfast was at 5 a.m., lunch at 10 a.m. and dinner at 3 p.m. That was true then, and it’s still true on menhaden boats today.

One of the things I like most about Farrell’s photographs, and perhaps the most important reason that I keep going back to them, is that he was drawn to these kinds of simple, ordinary moments in life.

They are the moments that usually remain unseen in historical photographs, but Farrell was drawn to them: children playing, mothers and daughters working in a shrimp house, fishermen playing checkers on a menhaden boat.

They’re hauntingly rare in other kinds of historical records, too. I love that Farrell turned his camera toward them, and I love even more that he found so much beauty in them.

Special thanks from the author

I would like to thank the following people for so generously sharing their time and knowledge with me: Ernest “King” Davis in Beaufort, Steve Goodwin in Beaufort, Donnie Joyner in Southport, the late Charles “Pete” Joyner in Southport, Jimmy and Mae Moore on Oak Island, Tookie Potter in Southport and Capt. David Willis in Beaufort.

I also want to extend a special thanks to Barbara Garrity-Blake in Gloucester. Her work with the state’s menhaden fishermen is always an inspiration to me.

In addition, I got a tremendous lot of help from an extraordinary archivist, Kim Andersen at the State Archives of North Carolina (now retired), and from a no less extraordinary museum leader, Lori Sanderlin at the North Carolina Maritime Museum at Southport.

Finally, I’d like to thank the Southport Historical Society and the William Madison Randall Library at UNC-Wilmington for making the John D. Eriksen Collection available to me.

Thank you all so much. Writing history is such a joy when I get to spend time with the likes of you.