WINDSOR — For John M. Bunch of Tampa, Florida, the voyage of discovery as he traveled through his family history was perhaps more shocking than genealogy is for most people.

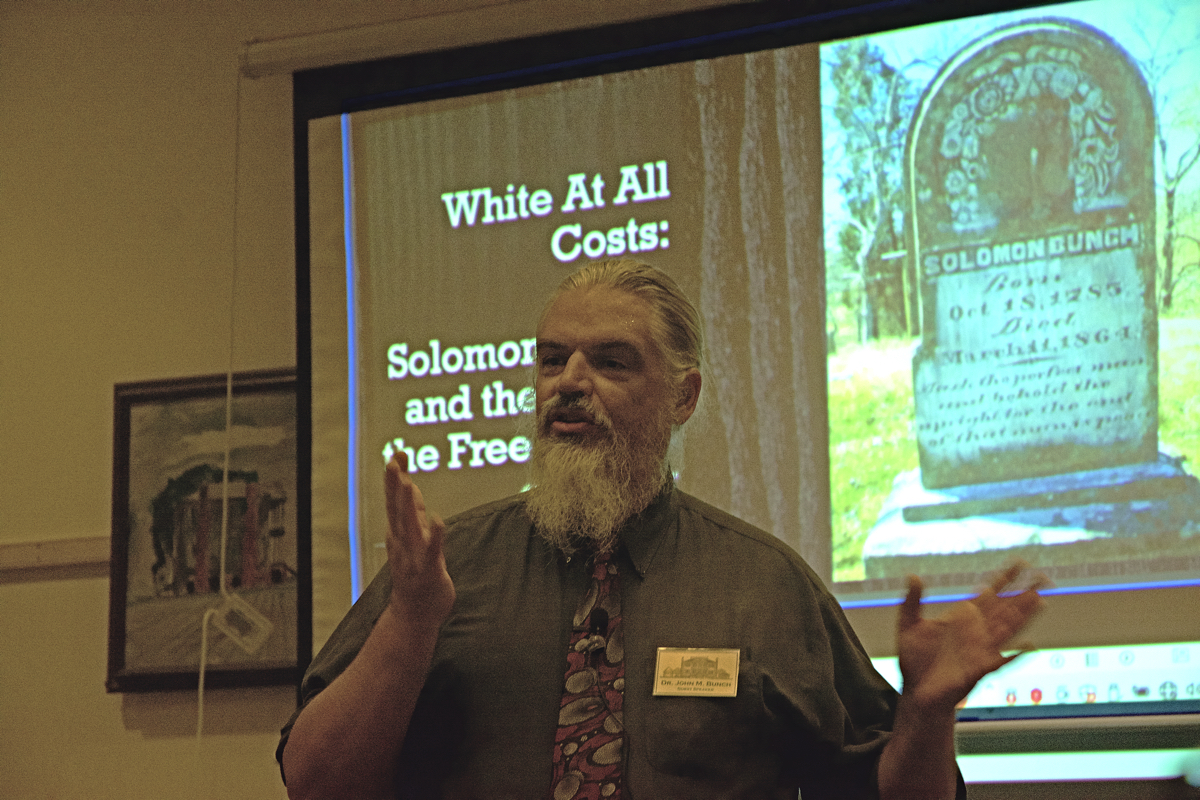

Describing his journey Saturday during the Historic Hope Foundation’s 10th Family History and Genealogical Fair at Hope Plantation near Windsor in Bertie County, Bunch said it took him to the earliest days of our nation’s history and ultimately delineated the story of race in America.

Supporter Spotlight

While growing up, he experienced two narratives of race.

“The … maternal side was mostly poor rural Scots-Irish. None of those people had slaves,” he said. “My grandmother was a fundamentalist Christian. She was very human. She insisted and made sure that I had a shared (view of) humanity that was loving, kind, with an appreciation of all races.”

The paternal side, however, viewed race very differently.

“The Bunch side was, ‘We don’t have any Black blood at all,’” he said.

Except the Bunch side was wrong.

Supporter Spotlight

There were hints, clues that suggested there was maybe more to the family history than the Bunch family was willing to acknowledge. There was an older cousin who traced the family tree back to a Bertie County man, Jeremiah Bunch, who was biracial.

“He interpreted it as a white man who had married an Indian woman,” Bunch said in a recent phone interview.

A few years later, an aunt did similar research, got the same results and simply rejected it, claiming it could not be true.

For Bunch, the real search began when Barrack Obama became president and his family tree was traced back to a John Punch who had come to America as an indentured servant from Africa sometime before 1640.

That’s when Bunch, who has a doctorate in social psychology and cognitive science, began a systematic and scientific search of his ancestry.

He traced his family tree further, before his ancestor Jeremiah Bunch, and concluded that he probably was, like Obama, also a John Punch descendent. He then had a Y-DNA test looking for the specific marker that would show African heritage on the male side.

The marker was present, but with the confirmation that he was of multiracial lineage came more questions about his family history, questions that held some painful answers.

Jeremiah Bunch’s son was Solomon Bunch, who was born in 1785. At some point in the early 1800s, after his father’s death, Solomon Bunch moved from Bertie County to Maury County, Tennessee. When he gets there, he faced a choice.

“He’s got to make a decision. ‘Either I’m going to be white, or I’m not going to be white,’” Bunch said.

Solomon Bunch chose to be white.

“He builds a business, builds a farm, and apparently does pretty well. Also he has slaves,” he said. “That bothered me for a long time … still bothers me, I suppose,” John Bunch added. “Why in the world would he, coming as a free person of color, is he going to turn around and have slaves. How does a free person of color do that? How are they going to justify that? From a modern perspective it seems inconceivable.”

But in antebellum Tennessee, the choices available to Solomon were limited. North Carolina, where he grew up, had specific laws defining race. In Tennessee, such choices did not exist.

“You’ve got to be either white or nonwhite. That’s his choice,” Bunch said. “He chooses to be white. He marries a woman and has slaves. From our modern perspective, you can’t justify that. But slaves were part of Bertie County (where he grew up) part of the culture. It’s something that must have seemed natural for Solomon.”

We do not know, however, what he was thinking when he chose to be white, and we may never know. He left no record of his thoughts on the decision, leaving his descendant John Bunch with no clear answer.

“I wish he had written a great letter like Frederick Douglass, but he was an ordinary man … motivated by ordinary human motivations.”

The discovery prompted John Bunch to examine how the history of race in the United States led to where we are today.

He began his talk at Hope Plantation noting that as a social psychologist his approach differs from that of a historian.

“The way I interpret history is always through the psychological lens. This (is an) ongoing narrative, so that you see history not as a TV show that ran and is now over. The historical forces of radical pro-slave powers and anti-slave forces, those are still with us, they still battle,” he said.

When John Punch was brought to the New World around 1640, enslavement of Africans in the British Colonies was not commonplace. It was not until 1661 that Virginia enacted the first slavery laws allowing a human being to become the property of another.

To create a moral basis to place another human being into permanent bondage requires a view of that person as less valuable and distinctly different.

“To justify that, you have to dehumanize the person. They’re Black, they’re not Christian, they’re from Africa, they don’t look like us. Let’s make them slaves. This is the vilification of Blackness,” Bunch said.

That dehumanization did not end with the freeing of enslaved people in 1865. Nor were the 200 years of enslavement or the years immediately following the Civil War the most profound example of racial animosity in our history. That distinction, according to Bunch, belongs to the early 20th century.

“It continues to grow past the Civil War. (It) reaches a peak in the ‘20s and ‘30s, pre-World War II,” he said. “That’s when you see this real hatred — lynchings, D.W. Griffith’s ‘Birth of a Nation’ comes out, this reinventing of the role in the Civil War to the Great Lost Cause. We are now on the downside of a vilification of Blackness, but it’s still there.”

The was the era of the “one-drop rule,” a time when states enacted laws declaring that any amount of African descent meant a person was Black and therefore subject to the laws restricting Black participation in society.

The laws, which no longer exist, were a peculiarly American view of race, according to author and sociologist F. James Davis.

“Apparently the rule is unique in that it is found only in the United States and not in any other nation in the world,” Davis wrote for PBS Frontline.

The one-drop rules were largely rescinded or found unconstitutional, but not until after World War II. Still, their legacy remains, Bunch said.

The Jim Crow era, the Ku Klux Klan and other vestiges of the one-drop rule live on in the form of modern-day white supremacists and the political movements they support. Those forces, though, are counterbalanced by other mostly white groups.

“Throughout history, you’ve got this dichotomy between whites on the one hand who just want to find someone to be cruel to. On the other hand, you’ve got this group of white people who is your typical white liberals. And American racial politics to me seems like it’s always this balance between radical pro-slavery forces and this Age of Enlightenment liberal force,” he said. “What happens is neither really get what they want. And the people that are caught in the center, never really advanced like they should. Because what you end up with is, you’ve got people on both sides who can make themselves comfortable that they’ve done what they’re supposed to do.”

He said that for those caught in the middle, despite some improvement, the conflict remains.

“It’s no less intense than it ever was. It’s just changed forms,” Bunch said.