Brunswick County beach towns are back to square one in a push to ensure potential offshore wind farms are out of the line of sight from shore.

“Nothing has changed,” said Village of Bald Head Island Councilor Peter Quinn. “We’re still in the exact same situation. Nothing has been addressed.”

Supporter Spotlight

The village council first adopted a resolution in 2015 urging the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, or BOEM, to establish a buffer for offshore wind energy leases no closer than 24 nautical miles, or about 27 miles, off North Carolina’s southern coast.

In May, councilors once again passed a similar resolution, a move that triggered other beach towns in the county, including Sunset Beach, Ocean Isle Beach, Caswell Beach, most recently, Oak Island, and the county board of commissioners to follow suit.

As opposition mounts along North Carolina’s southernmost coast to wind turbines within the viewshed, or line of sight from shore, the federal government is ramping up proposed plans for what could be the first wind energy farms off the state’s coast. BOEM earlier this month began hosting a series of virtual public meetings as part of the agency’s environmental review of the proposed project’s construction and operations plans.

In all, three wind energy areas, or WEAs, spanning more than 307,000 acres have been identified off the state’s coast for potential commercial wind energy development.

These areas include the Kitty Hawk WEA, Wilmington West WEA and Wilmington East WEA, the latter two of which are off Brunswick County’s ocean shoreline.

Supporter Spotlight

BOEM has established a 24-nautical-mile no-leasing buffer for Virginia and the Kitty Hawk WEA. A 33.7 nautical mile no-leasing buffer has been established to protect the Bodie Island Lighthouse.

Meanwhile, the proposed lease sites offshore of Brunswick County are considerably closer to the coast, raising concerns about how the potential for hundreds of wind turbines towering over the ocean and changing the view of the horizon from shore might impact, among other things, tourism.

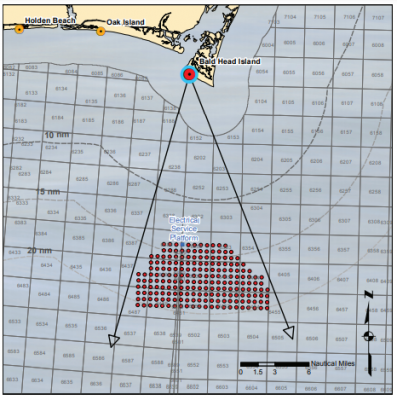

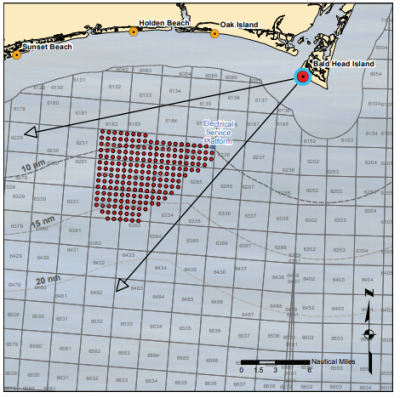

As it stands, the closest border of the Wilmington West WEA is 10 nautical miles from shore. The Wilmington East WEA would be as close as about 15 miles from Bald Head Island.

Mockup photographs of wind farms within those distances to Brunswick’s shores are on BOEM’s website.

John Filostrat, director of public affairs of BOEM’s Gulf of Mexico region, said in an email response to Coastal Review that BOEM is preparing a proposed sale notice that will identify potential lease areas in the Wilmington East area.

A draft of the proposed sale was discussed in July at a meeting of the Regional Carolina Long Bay Intergovernmental Renewable Energy Task Force.

“BOEM anticipates holding an auction in the Carolina Long Bay region next year,” Filostrat said in the email. “Any potential lease sale would be informed by science and other information collected from the Carolina Long Bay Intergovernmental Renewable Energy Task Force, ocean users, and key stakeholders.

He explained that BOEM’s environmental review process includes potential impacts of wind turbines within viewsheds.

“Visual impacts are one of many resources that BOEM evaluates through its National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) process,” he said. “BOEM requires all offshore wind project proposals (as detailed in an offshore wind developer’s Construction and Operations Plan) to include viewshed mapping, photographic and video simulations, and field inventory techniques, as appropriate, so that BOEM can determine, with reasonable accuracy, the visibility of the proposed project from shore. Simulations should illustrate sensitive and scenic viewpoints.”

Property owners and visitors to Block Island, a small island a little more than 10 miles south of mainland Rhode Island, have a front-row view of the first commercial offshore wind farm in the United States.

The 840-foot-tall turbines are little more than 3½ miles offshore.

“We’re right at ground zero,” said Block Island property owner Rosemarie Ives.

The 30-megawatt wind farm is operated by Orstead, a Denmark-based company. The wind farm’s five turbines became operational in December 2016. They generate enough energy to power 17,000 homes, according to Orstead.

Block Island, once powered by five diesel generators, is now powered entirely by offshore wind, according to information provided on the company’s website.

The island’s local government board, the New Shoreham Town Council, supported the project. The response among property owners – there are about 1,000 year-round residents on the island – and tourists have been a mixed bag.

Ives and her husband were part of a handful of property owners, including a family on the mainland, thrust into the spotlight as they fought the project.

Three months out of the year, they leave their home on the West Coast to vacation at the cottage, which sits atop the island’s bluffs, offering a panoramic view from south to east.

During a recent telephone interview, Ives described the scene from the cottage, one that has been in her husband’s family since 1924.

“We get to see all five of (the turbines) and they’re not moving one inch today because there’s absolutely no wind,” she said. “I remember the first time we came here in 1967 and I thought, oh my God, this is like nothing else. I think it was almost hypnotizing. It used to be quite majestic. It’s not the same.”

Now, the dark sky that stretched over the ocean is peppered with blinking lights on the turbines.

“You’re not having the experience of seeing the ocean rise above,” she said. “There’s something spiritual, magical about looking out and seeing the ocean and seeing the sky and now you’re seeing these turbines that are right there.”

She describes the process for which the wind farm was approved “complex” and “convoluted,” one that she said inflates the project’s touted benefits.

Ives is a former mayor of Redmond, Washington, for 16 years, to be exact. She chaired the U.S. Conference of Mayors Sustainability Task Force, and was an initial signatory of the Mayors Climate Protection Agreement.

She refers to her background with an emphasis that she’s not anti-renewable energy.

“I was green way, way before it was politically correct,” she said.

There’s a seemingly similar sentiment among those in Brunswick County asking for the buffer.

When the Holden Beach Property Owners Association adopted in 2018 a resolution asking BOEM for the buffer, its members were intent on making sure it was not worded in a way that could be construed as anti-renewable energy.

“We debated all that and tweaked the wording to make sure we didn’t across as anti-wind,” said Tom Meyers, the association’s president. “We’ve been mostly focused on the view from the beach strand. It’s the lights as much as what we’ll see in the day. We’re all on the same page. When you go out to the ocean and you look out at the night you just want to see the sky. I really wish the town would pass a resolution and take a stand here. Once you’re changing the view from the beach you’re impacting a lot.”