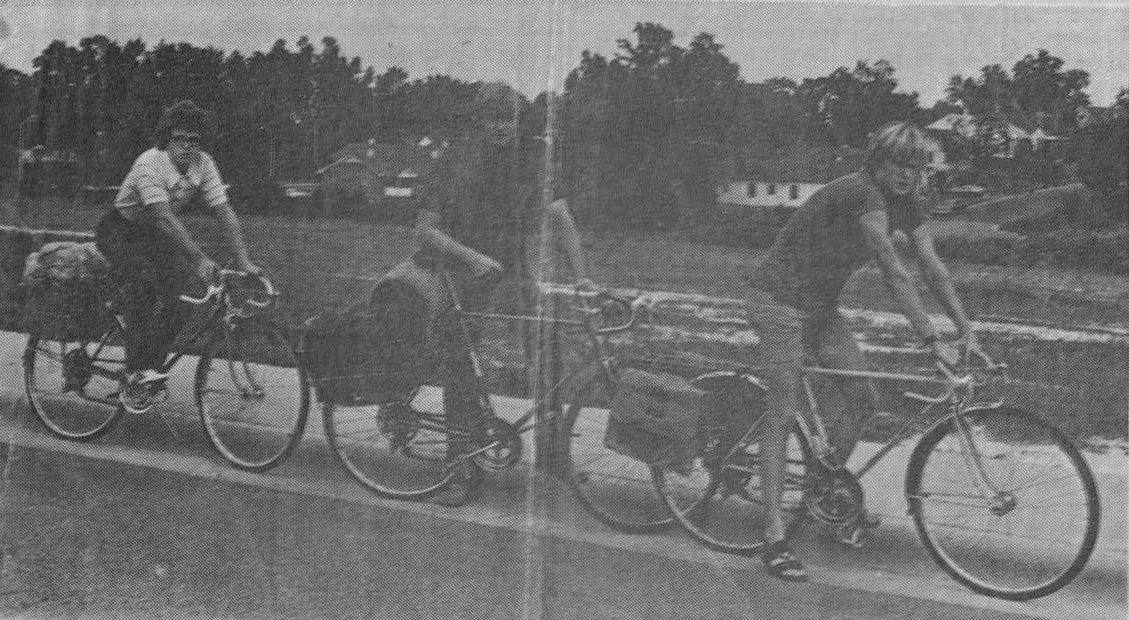

Fifty years ago, 17-year-old Kevin Duffus and his two high school buddies set off in the early morning hours of Aug. 18 from Greenville on their 10-speed bicycles, kicking off a 425-plus mile circuitous ride to the Outer Banks.

Although it lacked the death-defying drama of movie road trips, the five-day journey was a classic example of an intrepid teenage adventure that can set a young man’s path in life. For Duffus, who later became a researcher and chronicler of Outer Banks maritime history and is a contributing writer for Coastal Review, the trip charged his curiosity about the coast and doggedness to uncover its secrets.

Supporter Spotlight

“So generally speaking, when I look back and think about it, to me it’s pretty remarkable that was my first experience with the Outer Banks,” he said in a recent interview, “but it sort of became, you know, my future.”

It is also noteworthy because at the time, long-distance bicycling was almost nonexistent, certainly in rural northeastern North Carolina.

Back in 1971, Duffus was a senior at Rose High in Greenville, where his family had moved to two years earlier from Missouri. Even before he arrived in North Carolina, he had been intrigued with Ocracoke since watching the movie “Blackbeard’s Ghost,” loosely based on the famous pirate who was killed in waters off the island.

Shortly after moving, he read Outer Banks’ author and historian David Stick’s book, “Graveyard of the Atlantic,” and was captivated by the story of shipwrecks off the coast.

Duffus wanted to see the Outer Banks, so he persuaded his friends Gary Snyder and Bob Thurber to make it a biking expedition. The three young men already knew each well from scuba diving together, including during a trip the year before where — at Duffus’ suggestion — they snuck down to Florida during Christmas break to go cave diving. They also devoted considerable time hunting for the U-352 World War II German submarine off Cape Lookout.

Supporter Spotlight

“Kevin had a very distinct love of adventure,” Thurber recalled in a recent telephone interview. “He was just very energetic and always wanted to go do things. He thought that this would be a physical challenge and a rewarding week spent on the road.”

Thurber had a yellow Schwinn 10-speed bicycle that he equipped with toe clips and saddle bags.

“We weren’t trained cyclists,” he said. “We just kind of had some bikes, they weren’t really ultralight road bikes either. They were pretty chunky.”

Snyder also had a 10-speed. Between them, Thurber recalled, they packed two tents, sleeping bags, and some food and water, with refills obtained along the way. They wore their everyday clothes and footwear but no sunglasses or even hats. Sunscreen didn’t really exist and of course, there were no cell phones.

“Imagine — we were stupid — I mean I was wearing some idiot sandals,” Thurber remembered with a laugh. “No biking pants, probably just some cargo shorts. We were not smart about this at all.”

Thurber, who is vice president of engineering for Raycom Media outside Montgomery, Alabama, said they all were fried by the sun and tortured by bugs, but they kept going and never considered giving up.

“Oh, yeah. The insects on that run up to the Outer Banks were tough,” he said. “We were kids. We were bulletproof, you know?”

The trio decided ahead of time that everyone should keep their own pace, Thurber said, which meant that for much of the riding, there was not much talking but a lot of thinking. When they were together, he said, they had an easy camaraderie and he said he doesn’t recall any arguments.

“My recollection is that the trip itself was a pretty single-minded purpose, kind of myopic,” he said, adding that no one kept a dairy. “You know, we’re going to get these miles down and put it down in the book that we did it. We were just knocking down the miles.”

Which relates to what Thurber said is his strongest memory of the trip.

“In general, it was the requirement for perseverance,” he said. “You know, going along the swamp, I was tempted to throw the bike in.”

The biggest mistake they made was going north to south, he said, which had them riding the whole way into a headwind. But just being on the bike highlighted every detail of their surroundings. As often happens after high school, the friends lost touch with each other, although Thurber and Duffus recently reconnected.

“We got to experience the smells, the sun, the wind,” Thurber said. “That kind of macro lens was incredible for me. I really enjoyed it.” Even the long stretch of miles by the bombing range was far more interesting because he could see the birds and the environment. “It was like walking on a nature trail, really.”

No doubt the bike trip was “physically brutal,” he said, but it changed his life in a positive way.

“I think it was an incredible source of self-confidence for me,” he said. “You know, ‘I can do this!’ Doing it, finishing it — I felt good about myself in that I felt that it was a win.”

Duffus, who had mapped out the route and figured out stops along the way, had focused on fulfilling two main objectives: climbing the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse and then taking the ferry to Ocracoke.

The first stop was in Pactolus, where they took a brief nap on a church porch. Then on to Little Washington, where they were able to catch some breakfast and another brief nap, this time under a school porch.

After resuming their trek, they reached Lake Mattamuskeet Lodge by sundown, and started pitching their tents along the side of the road, Duffus recounted, “which was really kind of crazy — I couldn’t imagine doing that today.”

Soon, a friendly ranger stopped them and told them that wasn’t a great place to spend the night, and instead got them a room at the lodge, which then was still open. The young men were even served meals, along with lodge’s guests, and were able to take showers.

The ride on the next day from Engelhard to Manns Harbor on U.S. 264 was desolate, Duffus recalled. As they pedaled along the side of the open road, military jets flew low over the adjacent bombing range, dropping test bombs on targets.

After going through Manteo, the trio turned onto N.C. 12 and the northern border of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore. Finally at about 7 p.m., they pulled into the Oregon Inlet campground, where the exhausted boys were turned away by the park ranger because they didn’t have a reservation. Fortunately, a kind man overheard their conversation and let the boys pitch their tents on his campsite.

“Back then, I can’t say this for certain, but I don’t think that anyone had ever done a bike ride like this, at least to the Outer Banks by camping,” Duffus said. “Now you see people doing it all the time, but this is pretty revolutionary in 1971.”

People were generally very friendly and quite surprised to see three teenagers from Greenville traveling on their bikes, he said. A lot of people, especially on the ferries to Ocracoke and to Cedar Island, were curious about them and would come up and ask questions.

Back then, the ocean was visible from the highway on Hatteras Island because the dunes were lower, Duffus remembered. The villages were mostly houses with a couple of stores and a few motels. The few tourists they saw were mostly there to fish.

The barrier islands were still relatively undeveloped and uncrowded, and traffic was light.

“I convinced my friends it was going to be an easy ride because there were no hills, but I didn’t consider the Bonner bridge to be a hill. Also, this was in August and there was a southwesterly wind that was blowing like 25 to 30, right in our faces all the way to Hatteras, and then even down to Ocracoke. The headwind was just brutal.

“We parked our bikes with all of our possessions without a thought and went up that lighthouse. I mean today, you might come down and your bike wouldn’t be there. We didn’t have bike locks or anything.”

Duffus said that his great-great-grandfather was an 18-year-old Union soldier who was part of an amphibious landing on Hatteras, and he is pretty confident that his ancestor’s unit had discovered that the lighthouse was missing its Fresnel lens.

“You know, so 110 years later, I’m standing in the same spot that my great-great-grandfather was,” he said, noting the coincidence of their crossed paths and roles in the history of the lens.

Years later, Duffus tracked down the missing lens from the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse and wrote a book about it.

That evening they ate at the Channel Bass in Hatteras village. They took the ferry to Ocracoke and then Duffus told his friends that they had to ride 13 more miles to Ocracoke village.

“‘What!?’” they said. “They thought the trip was gonna be over.”

At the community store in Ocracoke village, Duffus innocently asked some local men on the porch where he could find the 100-foot-high cliff he saw in the movie overlooking the bay where Blackbeard was killed.

The men paused and smiled a little, and then one spoke up in a thick island brogue:

“‘Boy, you’ve come to the wrong place. The highest place on this island is 8 feet,’” Duffus recounted. “That was sort of my indoctrination that you shouldn’t get history from movies from Hollywood.”

After high school, Duffus became passionate about sailing and worked at Raleigh’s WRAL-TV, where he eventually produced an award-winning documentary about the history of the state’s lighthouses and the lightkeepers. Duffus has since established himself as a maritime historian, producing several documentaries and writing numerous books and articles, including for Coastal Review, about North Carolina’s lighthouses, shipwrecks and Blackbeard the pirate.

In 2004, the late David Stick, who over the years had become Duffus’ mentor and friend, wrote in a letter: “I was fortunate to have been involved with Kevin when he first began his research on the Outer Banks and its lighthouses and shipwrecks, for at that time, I was considered an authority on those subjects. Years later, he is the authority to whom I must turn.”

As Duffus sees it, his career course was set before he graduated high school.

“You know, none of that would have happened, I think, if I had not read David Stick’s book and gone on this bike ride. None of this stuff would have happened.”