The state Department of Transportation is evolving in how it tackles runoff along North Carolina’s more than 80,000 miles of roadway, adding a host of nature-based designs to slow stormwater, reduce flooding and improve water quality.

“We’re anticipating about a 60% increase in the number of tools to be added to the toolbox,” Andy McDaniel, the department’s highway stormwater program supervisor, said in a recent telephone interview.

Supporter Spotlight

That toolbox is the department’s stormwater design manual, the how-to on implementing stormwater control measures along the state’s roads.

The manual has been updated only twice since it was created in the late 1990s.

The latest update, which is expected to be finalized by year’s end, will be major, McDaniel said.

The department has hired a consultant to assist in searching nationwide to glean nature-based solutions and innovations other state transportation departments and federal agencies are using.

“It reflects our approach to how we intend to more thoroughly incorporate nature-based solutions into transportation,” he said. “We see it as a whole program level initiative where nature-based solutions have a spot in the planning in avoidance and minimization phases of transportation planning. It has a place in the hydraulic design of the project and it also has a place for post-construction maintenance. So, we are looking at it from a very holistic perspective.”

Supporter Spotlight

Department officials already have been creating, installing and testing some of the natural designs, like the commonly called bio-embankments, that will be added to the manual.

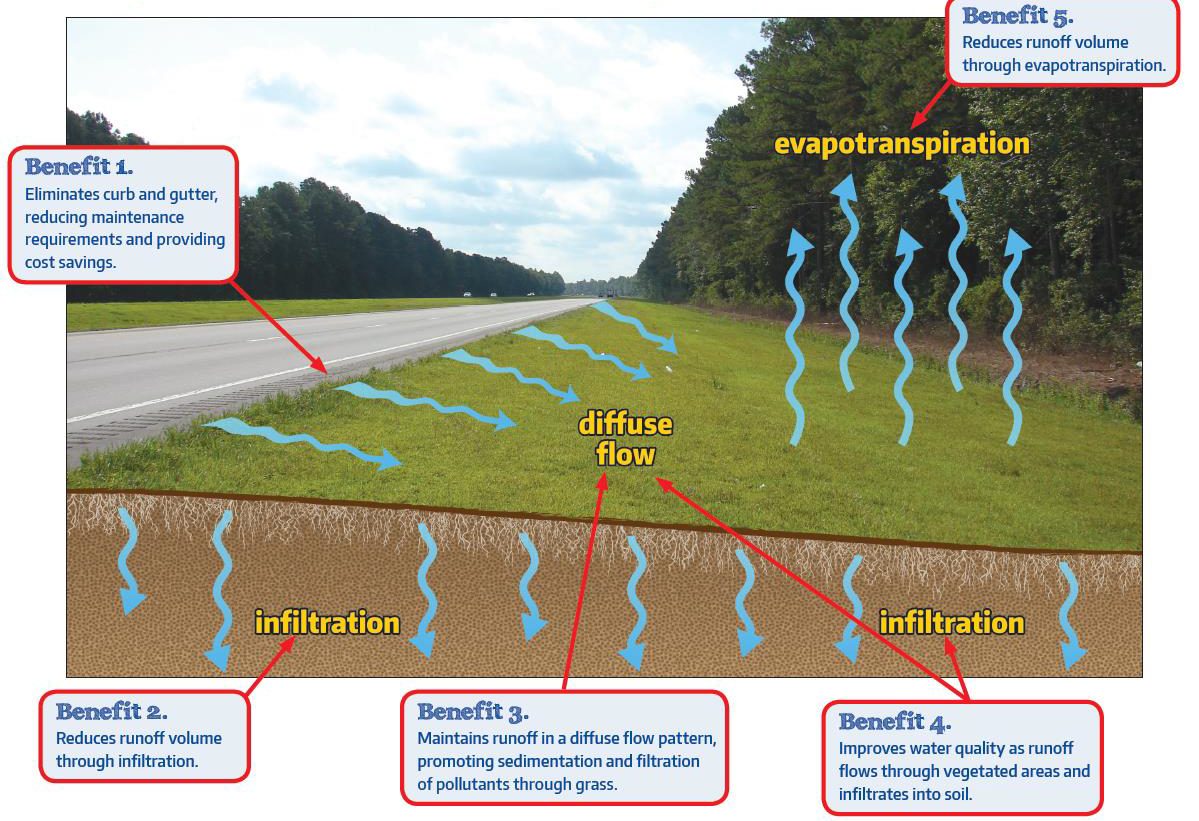

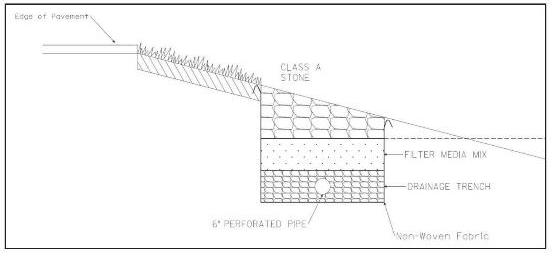

A bio-embankment is a trench that runs parallel to a road surface. Rainwater is diverted into the trench, which slows down and filters the runoff.

“It reduces the flow rate so it really acts more like a natural system, natural interflow through the soil,” McDaniel said. “It filters the water, so, from a coastal perspective, these are very good for removing bacteria, which is a problem in shellfishing waters.”

Their design is based on reviews of similar designs used in five other states.

“That’s an example of a tool that will be moving forward,” McDaniel said.

DOT has also been using a type of porous pavement that allows rainwater to absorb into the pavement then flow laterally out from the roadway surface onto the shoulder section, where the runoff is infiltrated. This pavement, a blend of holey asphalt, is used commonly along the coastal region where roadways are flat.

Flat roads pose a greater risk of hydroplaning.

The porous pavement causes very little water spray to come up from a vehicle’s tires.

“That has not only a safety benefit, but it also reduces pollutants considerably because you don’t have the under-washing of the carriage of the car,” McDaniel said. “That can be useful if you’re hauling say, hogs from Duplin County somewhere, and not having that spray washing the hog truck down is going to reduce fecal coliform.”

He said he anticipates this type of pavement will be added as a stormwater control management measure in the manual, a move that will make North Carolina the third state in the nation to include it in a state transportation stormwater best management practices manual following Texas and California.

The updated manual is also expected to include biofiltration conveyance, a tool that may not be as commonly used along the coast as it will be in the piedmont because it is designed for steep slopes, but one that also slows and filters runoff.

One such system has been installed in Brunswick County, where runoff is infiltrated before the water flows into a tributary of the Lockwoods Folly River.

North Carolina State University researchers have been monitoring a biofiltration system built at a state-operated rest area in Alamance County and found that runoff is discharging at almost half of the capacity it was prior to the installation of that system, McDaniel said.

“It was pretty amazing how well this worked,” he said.

These more natural alternatives to stormwater management will, in at least some cases, mean the department will have to dig deeper into its pockets.

Traditional stormwater systems, say for example, a riprap stormwater conveyance, does not require much engineering and takes uses less material than biofiltration.

“I dare say this could very easily be on the order 10 times or more expensive,” said hydraulics engineer Stephen Morgan with NCDOT’s hydraulics unit. “It’s hard to compare some of these because, stepping back, we’re trying to figure out what’s the performance standard or what are we trying to achieve and you have to figure that out for every single site. We have many, many miles of roadway across the state and we look at the entire system and, in particular, certain areas along our system. It’s both done holistically and it’s done at a project level.”

There are a number of variables that go into what types of nature-based systems may be best suited for different areas.

Before designs are drawn, transportation planners must think about the soils in the area a road may be built, how big the roadway needs to be, and the surrounding environment.

“If this is a roadway facility that’s designed to take people from point A to point B in a fairly rural area then we’ll really focus in highly on having vegetated shoulder sections and vegetated median that will allow water to infiltrate without having to build a lot of structural facilities along the roadway that require a lot of expensive maintenance,” McDaniel said.

He said that over the years, officials have conducted a tremendous amount of research on how to improve the native roadside environment of the state’s transportation system. Specifically, they’re trying to determine how to get shoulder sections to infiltrate stormwater without having to build highly engineered systems that require a lot of maintenance and annual inspections.

He calls these solutions the “holy grail” of what they’re trying to do.

DOT has a handful of research plots in different soil conditions across the state in the mountains, piedmont and coastal regions.

“These are a great story because you have a triple bottom-line benefit by improving the infiltration capacity of the right-of-way,” McDaniel said. “We are reducing runoff, we’re better treating pollutants, which is great for the environment, and, by selecting native plants thoughtfully that have nice flowers we beautify the road.”

Stormwater management officials within the department want to lay out as many different options as possible and, hopefully, partner with local governments to implement more nature-based systems, Morgan said.

For example, a municipal beautification board could maintain the wildflowers and native vegetation planted in a bio-embankment system.

“Stormwater and runoff and floodwaters and any movement of water across the land is irrespective of boundaries, so I think one of the biggest — it’s both a challenge and an opportunity — is how we can develop partnerships with our neighbors along the right-of-way,” he said. “From our standpoint, we would like to do a lot more of these, but the maintenance burden associated with these is tremendous, depending on the type, and that’s why we want to expand the toolbox and try to optimize some less maintenance-intensive devices. That’s kind of the philosophy that we’re trying to focus on is finding elegantly simple ways to manage our stormwater.”