Coastal Review Online is featuring the research, findings and commentary of author Kevin Duffus.

Crafted in France, admired by millions at a New York world’s fair, stolen from its lighthouse, buried during the Civil War, recaptured, returned and repaired at Paris, stolen again, and exhibited again: America’s most historic, most traveled, yet most disrespected lighthouse Fresnel lens has a story like no other.

Supporter Spotlight

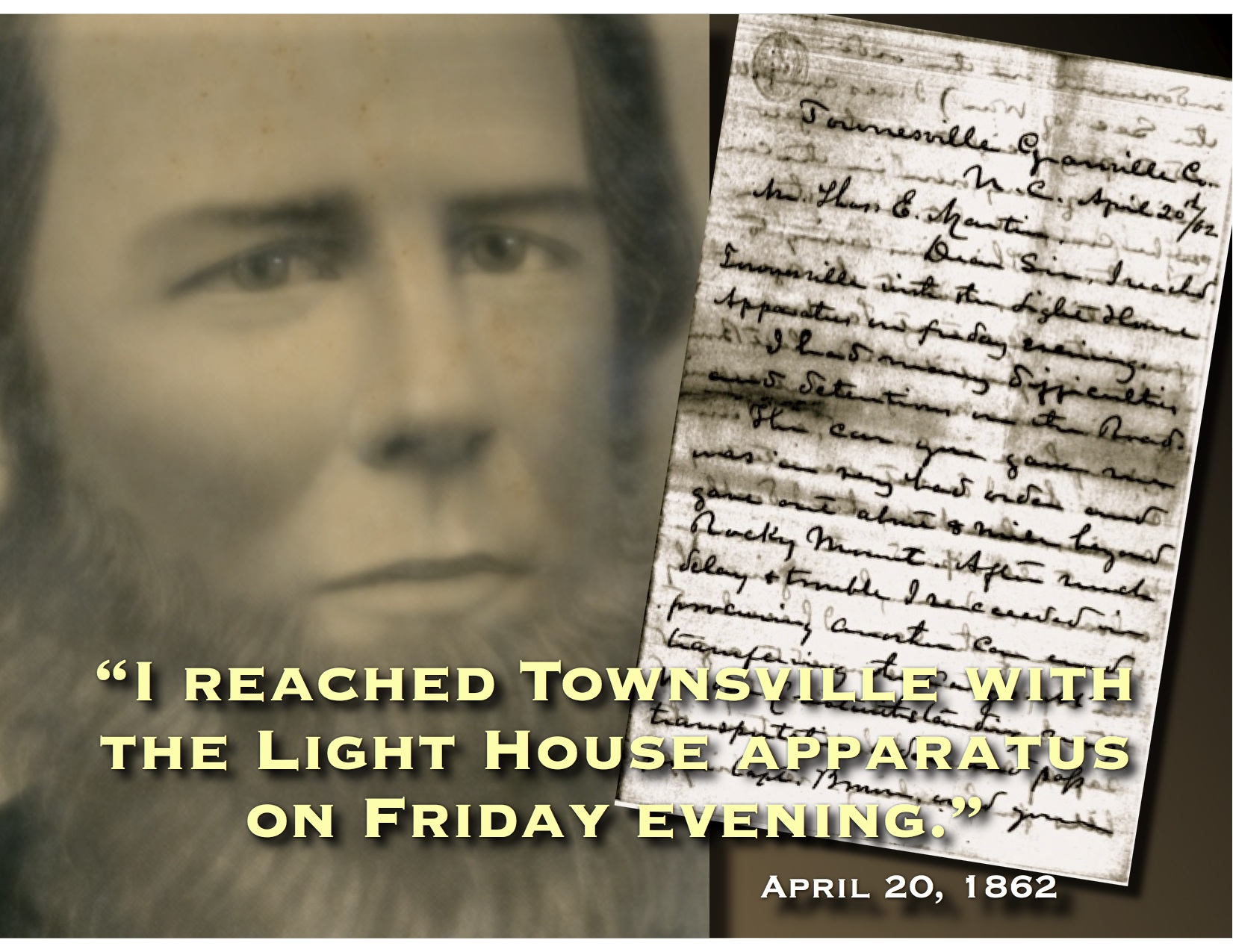

On Friday evening, April 18, 1862, 2 ½ miles south of the Virginia border at the outlying Granville County village of Townsville, a shrill steam whistle heralded the arrival of a train transporting a clandestine and highly coveted prize of war.

Inside a ramshackle boxcar was an apparatus that Union authorities threatened to recapture “at all risks,” including the destruction of the Pamlico River town that once harbored it.

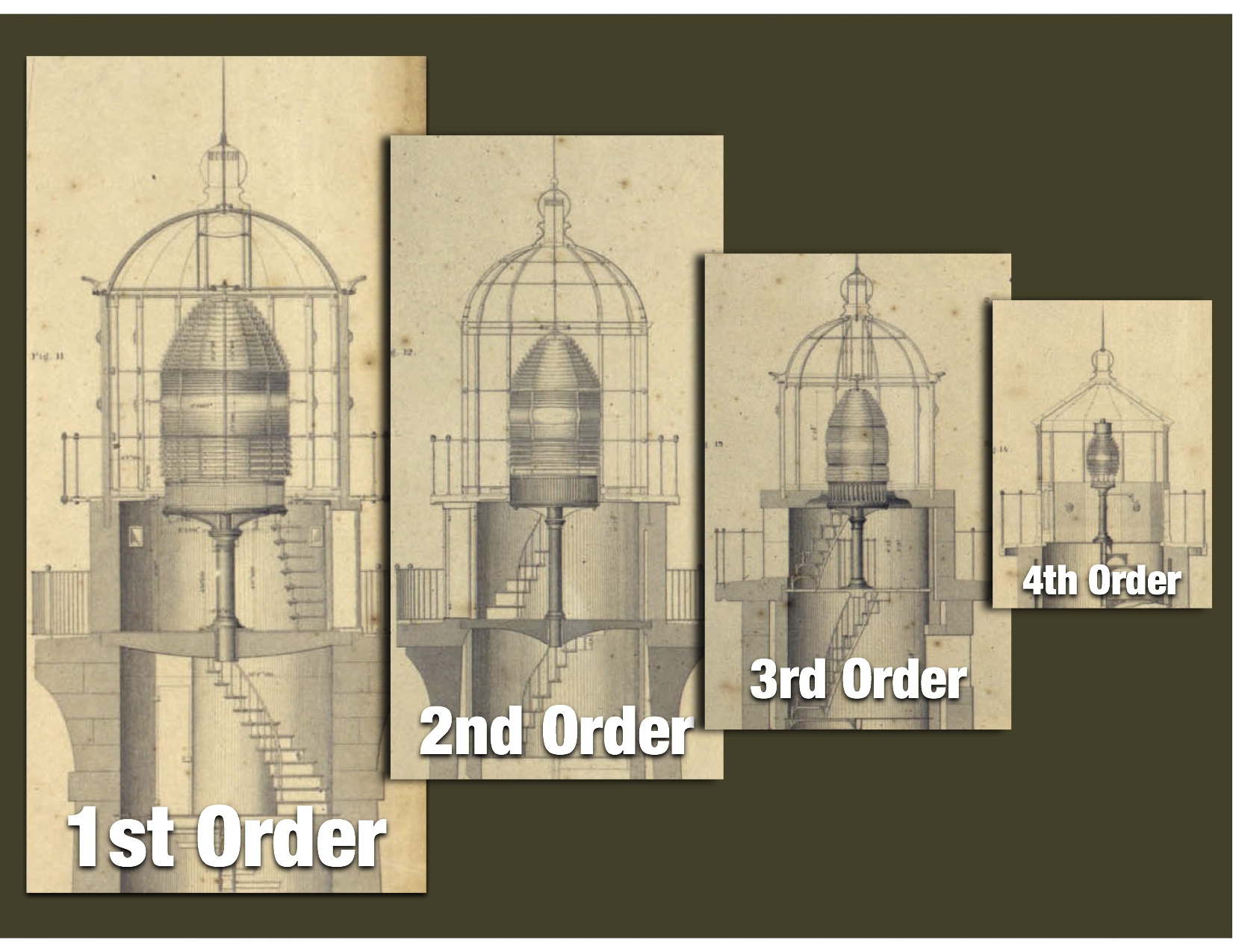

The object was a 6,000-pound, first-order Fresnel lens comprised of more than 1,000 crown-glass prisms and convex lenses. The various panels of faintly green-tinted glass had been dismantled and packed in 44 cotton-lined pine crates alongside 64 bronze precision castings.

When all the pieces were assembled by a skilled machinist using hundreds of delicate jeweler’s screws, the wondrous barrel-shaped optical instrument stood 12 feet high. At night, it magnified and projected 18 miles or more out to sea the light of an oil lamp, flashing a reassuring beam to passing ships once every 10 seconds. At midday, the lens looked like an immense diamond sparkling in the sun, the prisms refracting wavelengths of light splashing inside the lighthouse lantern room an artist’s palate of indigo blue, jade green, canary yellow and crimson red.

Many writers have described the Fresnel lens but none, perhaps, more credibly than the following from Alan Stevenson, the Scottish lighthouse engineer who perfected Augustin Fresnel’s original French design:

Supporter Spotlight

“Nothing can be more beautiful than an entire apparatus for a light of the first-order. I know of no work of art more beautiful or creditable to the boldness, ardor, intelligence, and zeal of the artist.”

The device described by Stevenson had just arrived at the railroad siding at Townsville. Few people could have imagined what it was, or its importance, or where it had been, or where destiny would take it.

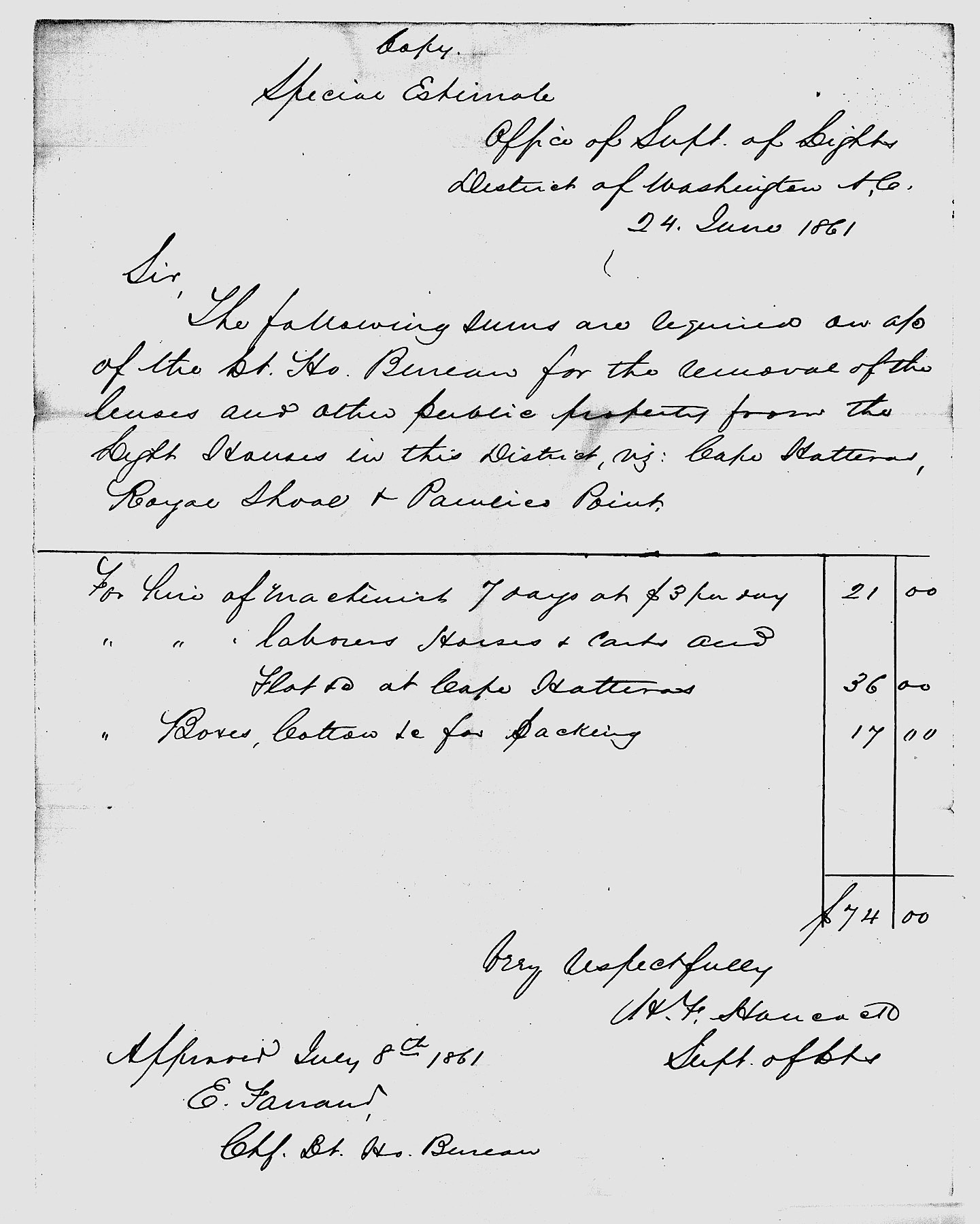

Ten months earlier, to prevent it from aiding the enemy, the Confederate Lighthouse Bureau in Richmond ordered the illuminating apparatus to be dismantled and removed from the lighthouse at Cape Hatteras, which, a decade earlier, had been regarded by the shipping industry and the U.S. Navy as America’s most important aid to navigation.

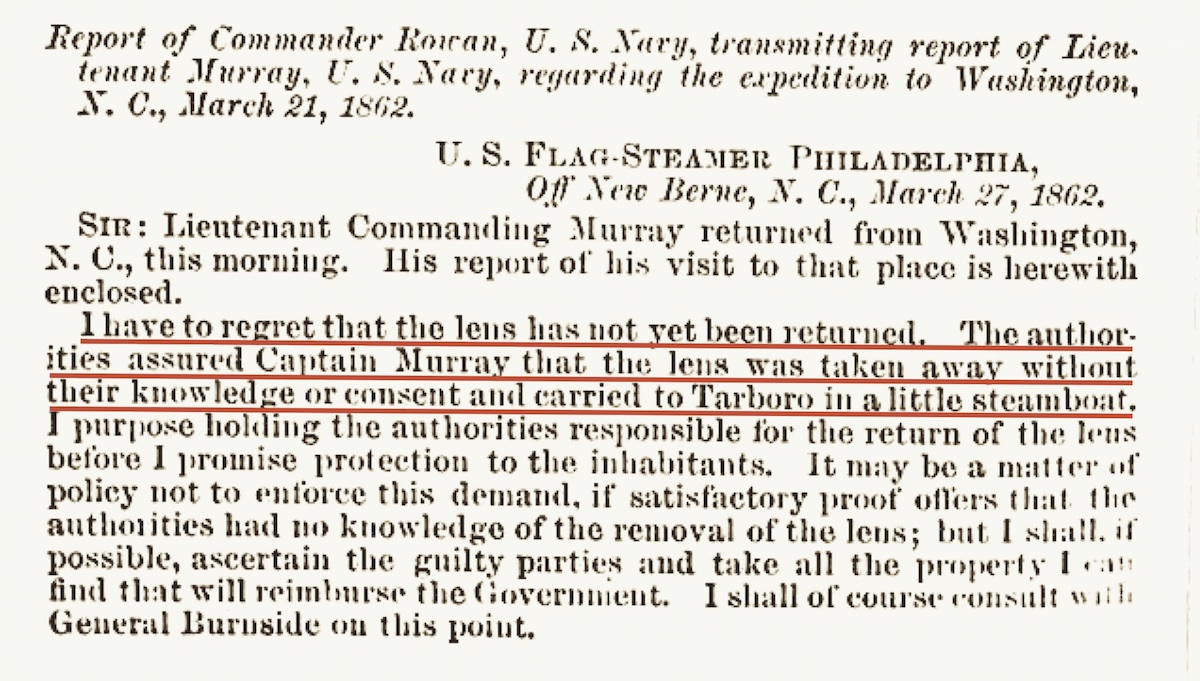

For nine months, the stolen Fresnel lens had been secretly hidden in the warehouse of John Myers and Sons on the Washington, North Carolina, waterfront. When news from Confederate informants reached the town in March 1862 that Union general Ambrose Burnside had dispatched four Union vessels and troops from New Bern to sail to Washington to recapture the lens, it was hastily loaded onto a shoal draft steamboat and transported up the Tar River to Tarboro.

Upon the Yankees’ arrival at Washington, town authorities informed them that what they were searching for had disappeared up the river the night before. Now on its way to a secret destination in the interior of the state, the recovery of the lighthouse apparatus had become considerably more difficult. Burnside shared the disappointing news in a letter to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton:

“The light belonging to the Hatteras light-house, which had been in Washington for some time, was removed up the Tar River in a very light-draught steamer, owned by one of the citizens, who was a large property-owner there. Notice has been given him that he must return the light or his property will be seized or destroyed.”

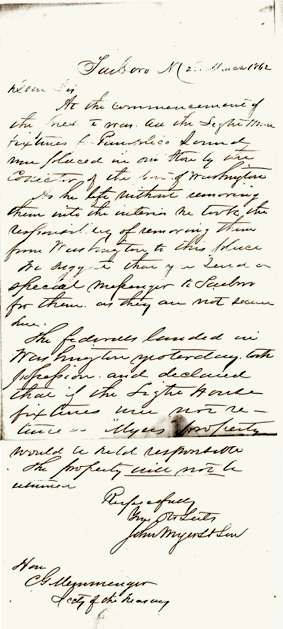

The “large property-owner” and owner of the steamer was John Myers. At Tarboro, Myers wrote his own letter to the Confederate secretary of the Treasury. At the National Archives, I held and transcribed Myers’s original letter:

“We took the responsibility of removing (the lens crates) from Washington to this place. We suggest that you send a special messenger to care for them as they are not secure here. The Federals landed in Washington yesterday, took possession and declared that if the Lighthouse fixtures were not returned “Myers” property would be held responsible. The property will not be returned.” For added emphasis, Myers underscored “will not.”

The Yankees did not torch Washington — at least not then — but Myers’ steamboat was eventually captured and sunk near Tarboro.

The high-stakes game of cat and mouse had become an embarrassment at the highest levels of the federal government, including for President Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward. They were determined to reestablish the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, not only for humanitarian reasons, but more importantly, as a symbolic proclamation proving that the Union, like the lighthouse, would prevail.

The power-obsessed Seward, who was said to have fancied himself more a prime minister, once boasted that he could “ring a little bell and cause the arrest of a citizen.” Seward’s law firm in lower Manhattan opened an investigation of the keeper of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, who participated in the theft of the lens. Luckily for the Trent Woods (now Frisco) resident and former lighthouse keeper, Seward’s little bell never tolled for Benjamin Fulcher, who had already escaped with his family to Hyde County.

The northern press, too, expressed their disdain for the inhumane behavior of the Southern states’ Richmond lighthouse office, whose sole function seemed to be disabling lighthouses and hiding Fresnel lenses. This opinion was published by “Frank Leslie’s Illustrated News” in November 1861:

“Soon after the bombardment of Fort Sumter the Confederate Government, with that murderous indifference to human life which has distinguished them from the first, extinguished all the lights they could reach, and among others the lighthouse erected at Cape Hatteras.”

But the Cape Hatteras apparatus, important as it was to navigators, was not just an ordinary lens — it was already a nationally significant historic artifact. In 1852, it was one of the first two, “first-order” lenses purchased by the U.S. government from the Henry-Lepaute Co. of Paris.

First-order lenses were the most expensive, largest and brightest designed to serve in seacoast lights that had to be seen at the greatest possible distance by mariners. By 1915, there were 57 first-order Fresnel lenses in U.S. lighthouses out of a total of 766 lenses, the greatest number being those of the fourth-order serving harbor and river lights like the tower at Ocracoke or the Roanoke River screwpile lighthouse.

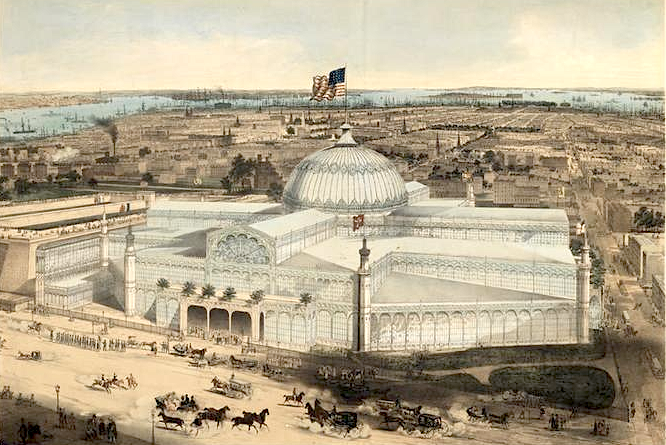

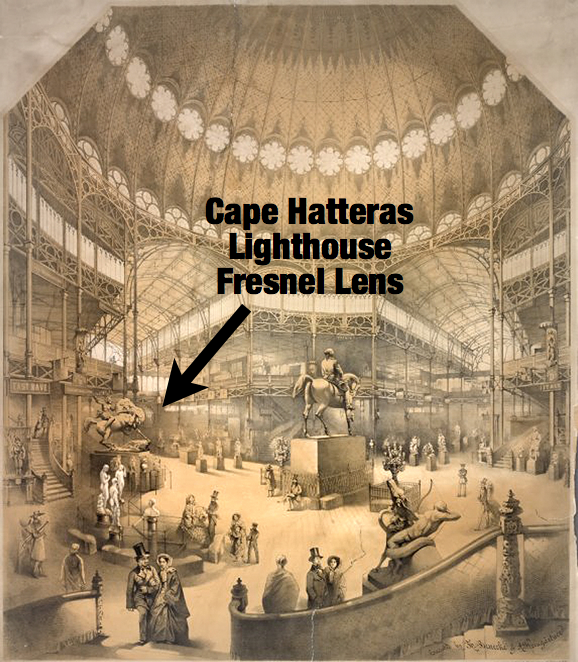

But before it was shipped to the Outer Banks, the Cape Hatteras lens was first assigned the temporary duty of guiding attendees through the south nave of New York City’s Crystal Palace on East 40th Street for the 1853 world’s fair known as The Exhibition of Industry of All Nations.

There, the lens was seen by more than 1 million visitors, including then-17-year-old Sam Clemens of Hannibal, Missouri, later known by his pseudonym, Mark Twain. My 10-year-old great-great-grandfather, Edward I. Horsman saw it too.

Up until 11 years ago, history seemed to have forgotten the fact — or didn’t consider it remarkable — that the lens had been the centerpiece of the newly established U.S. Lighthouse Board’s exhibit in 1853, until I rediscovered the occurrence for the first time and found the lens in a lithograph commissioned by P.T. Barnum in order to promote the exhibition.

The lens’ early brush with fame was not limited to the famous showman and the American humorist. The first man to supervise the assembly of the apparatus was a 38-year-old captain in the U.S. Topographical Engineers who, 10 years later to the day, was seated on horseback supervising the Army of the Potomac’s victory over Lee’s army at Gettysburg: Gen. George. G. Meade.

This was the lens that was ignominiously stacked in crates inside a newly arrived boxcar at Townsville on Easter weekend in 1862.

The man who volunteered to take the lens to a place of safety on behalf of the Confederate Lighthouse Bureau was 36-year-old Beaufort County physician, Dr. David T. Tayloe. Tayloe, the son of a former Pamlico district lighthouse superintendent, had previously evacuated his family from Washington to Hibernia, a property owned by his wife’s uncle, John Hargrove.

Today a state park on Kerr Lake, Hibernia was about 3 miles northeast of the train station, and it was there that the Cape Hatteras lens was removed to a secret “storehouse,” as Tayloe described in a letter. For 140 years, Townsville and Hibernia were assumed to be the last known location of the lens, its disappearance called “one of the great-unsolved mysteries of American lighthouse history” by the editor of Lighthouse Digest magazine.

In 1999, I began a search for the missing Fresnel lens, acclaimed by some as the “holy grail” of American lighthouses. Where would Tayloe and Hargrove have hidden the lens? Surely, they kept it close by as they were responsible for its safekeeping.

My exploration beneath railroad trestles, tobacco barns, and abandoned houses proved fruitless. However, a large and deep hole in the ground that once served as the icehouse for the estate seemed to be an intriguing and likely hiding place. But Hibernia turned out to be not as remote and invulnerable from the war’s depredations as was anticipated.

My research revealed that in early May 1865, 28,000 troops from Sherman’s army on their victory march from Raleigh to Washington, D.C., passed right through Townsville and Hibernia in a column stretching 25 miles long.

Wherever Tayloe and Hargrove had hidden the lens, Sherman’s soldiers did not find it, even though not a single Granville County chicken survived the army’s tornado-like swath of foraging.

Left behind in the clouds of dust, in my best estimation, and buried beneath piles of sawdust and blocks of melting ice was the “holy grail” of lighthouses — the Cape Hatteras lens.

It is hard to imagine that the same imposing, shimmering object that awed more than a million spectators at New York’s Crystal Palace had been buried at a remote farm 200 miles from the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, but many more desperate measures were taken during the nation’s darkest time.

Five months later in September, at the peak of tobacco-harvesting season, the 44 pine crates and 64 bronze precision castings were found by a Union patrol neatly stacked on the train station platform in Henderson, 20 miles south of Townsville.

No one knew how the Cape Hatteras lens got there or who delivered it. But if I had to guess, Tayloe and Hargrove were involved, and the pine crates likely emitted a pungent smell, having been hidden under piles of golden leaf for the 20-mile wagon trip south from Townsville to the Henderson tobacco markets.

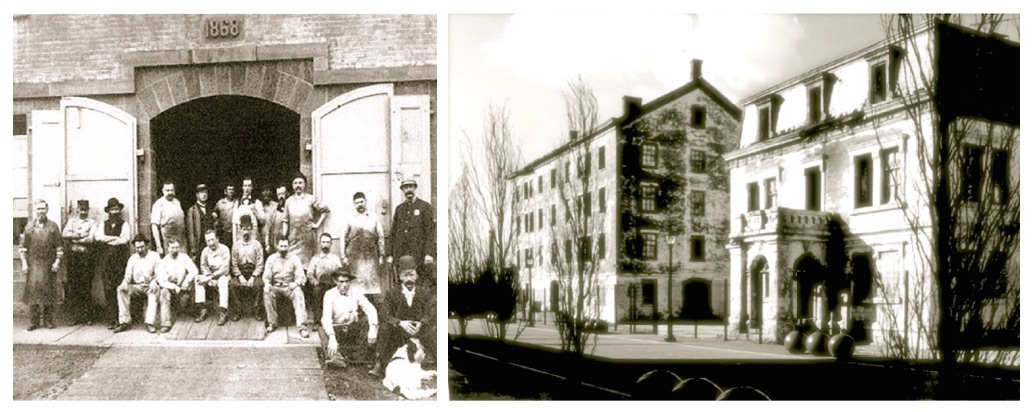

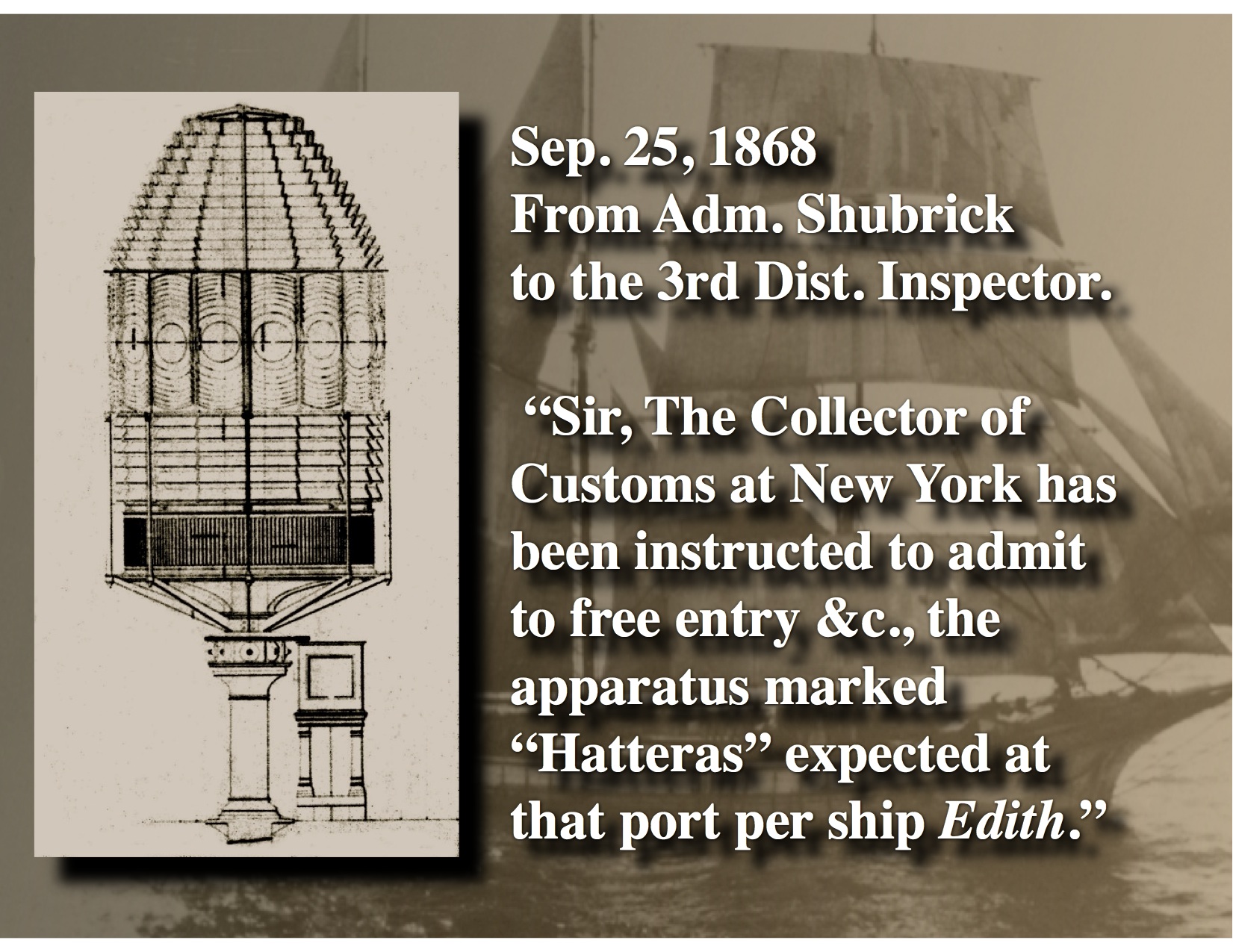

But where did the historic lens go from there? After many trips to the National Archives I followed the trail to the Lighthouse Service’s depot at Staten Island, then to Paris in 1867 where the lens was repaired and refocused, then back to Staten Island a year later to be held in storage pending the construction of a new lighthouse along one of the nation’s three coasts.

Finding that lighthouse, and the lens’ ultimate destination, proved to be the most painstaking piece of research I sought. There were at least a dozen possibilities but when I finally found the one document that had eluded untold numbers of fellow researchers at the archives, I was not entirely surprised. The 1853 Cape Hatteras Lighthouse lens was sent back home to the Outer Banks, not to the original tower built in 1803, but the new lighthouse completed in 1870.

For the next 66 years, the Henry-Lepaute Fresnel lens performed admirably, despite enduring a lightning strike and an earthquake. In 1933, the lens was famously photographed for National Geographic magazine proudly being polished by principal keeper Unaka Jennette, great-grandson of Benjamin Fulcher, the keeper who helped remove the same lens for the Confederates in 1861.

Throughout the years, the ocean crept ever closer to the base of the lighthouse and at sunrise on Wednesday, May 13, 1936, the light was extinguished, and the travel-weary lens flashed for its final time. The Cape Hatteras Lighthouse was, for the next 14 years, abandoned by the federal government.

All the while, the Cape Hatteras tower stood extinguished, its Henry-Lepaute lens remained at the top, but without the daily attention and loving care of its keepers and without the doors secured. The bronze and brass gears of the clockwork machinery that rotated the light were tarnished from neglect. Drifts of sand covered the once shiny, black-and-white marble tile floors of the landings. Windows were cracked or missing. Rainwater and salt spray seeped into the tower. Paint peeled from the walls. Guano stained the railings of the galleries and rust had begun its destructive process. Worst of all, the prisms and convex lenses of first-order illuminating apparatus — the pride of Paris and the former U.S. Lighthouse Service — began to disappear.

By 1944, two of the center flash panels had been jimmied loose from their bronze frames, and soon after, more disappeared. Years later, it was suggested that visitors to the lighthouse had been encouraged by unnamed Coast Guardsmen to take pieces of the lens, since the government did not expect the lighthouse to survive the waves that were clawing at its foundation. Whether souvenir hunters went about their business with the government’s permission is unproven, but it is without question that once word spread the prisms of the lens were there for the taking, the taking began in earnest.

By 1950, erosion had temporarily abated, and the Coast Guard wanted to reestablish the light, but by then the great lens was destroyed. Even though he likely knew little about its incomparable and eventful past, a National Park Service official called what happened to the lens “a disgrace.”

All 24 of the central dioptric flash panels were missing and two-thirds of the 1,008 crown-glass prisms had been taken. The beautiful brass incandescent oil vapor lamp was gone. Ironically, what Union authorities accused the Confederates of doing, had come to pass 89 years later. What was left of the historic lens was removed and replaced with an electric beacon made by Corning Glass Works.

From there, the remains of the historic Fresnel lens were shuttled around to various National Park Service storage facilities, including Little Kinnakeet Life-saving Station, where a couple of the surviving 170-pound prism-filled panels were stolen but eventually and disgracefully dumped in a ditch north of Avon.

Soon after I solved the mystery of the lost light in 2002 and positively identified the remains of the lens stored in the government’s Roanoke Island warehouse as the original 1853 Cape Hatteras Lighthouse Henry-Lepaute lens, the National Park Service agreed to loan to the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum in Hatteras village the surviving pieces so that the artifact could be conserved, publicly displayed and interpreted.

The first phase of the project was completed in 2005 and the lens was exhibited just as it was 152 years earlier at New York City’s Crystal Palace, albeit not as complete or awe-inspiring. One year later, on Oct. 27, 2006, the lens and its restored 1870 cast-iron pedestal were reunited at the museum. The total cost to the museum for the restoration and exhibit exceeded $100,000.

The location of the original Henry-Lepaute clockwork mechanism and pedestal displayed at the Crystal Palace in 1853 — the oldest surviving device in America — remained unknown until I located it in 2015 in the watch room of the Pigeon Point Lighthouse on California’s San Mateo coast.

The long and tempestuous odyssey of America’s oldest surviving first-order lighthouse lens had seemed to have reached an end. The historic artifact — indisputably a national treasure and an iconic symbol of Hatteras Island’s storied traditions of lighthouse keeping and lifesaving — will never be as it once was. Yet, a new chapter in the story had begun, hopefully what was expected to be a long and stable period of recognition, respect and admiration, viewed by 85,000 people annually at the museum.

There have been discussions during the past year that the National Park Service, in a future phase of its major repair and restoration project for the aging Cape Hatteras Lighthouse tower, may reclaim the fragile and incomplete Fresnel lens from the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum and return it to the top of the lighthouse. It is not known if a final decision has been made.

At the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum, however, the nation’s oldest surviving first-order Fresnel lens is safer and more accessible to the public, especially for those who are physically unable to ascend the 256 steps of the 20-story building to catch a partial glimpse of the lens through the narrow gap in the lantern room floor.

Instead, as it stands today and hopefully forever at the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum, the lens serves as a far more powerful light, an educational beacon, a uniquely American symbol of our maritime history.

On that point, we might imagine that Benjamin Fulcher, John Myers, Dr. David T. Tayloe, General Ambrose Burnside, Phineas T. Barnum, Gen. George Meade, Mark Twain, Unaka Jennette, Alan Stevenson, Abraham Lincoln, and Augustin Michel Henry-Lepaute would all agree.