Coastal Review Online is featuring the research, findings and commentary of author Kevin Duffus.

In 1942, more than 65 German U-boats waged a withering campaign along the nation’s eastern seaboard against Allied merchant vessels and their military defenders to disrupt or entirely sever transatlantic supply lines fueling the war effort in Europe.

Supporter Spotlight

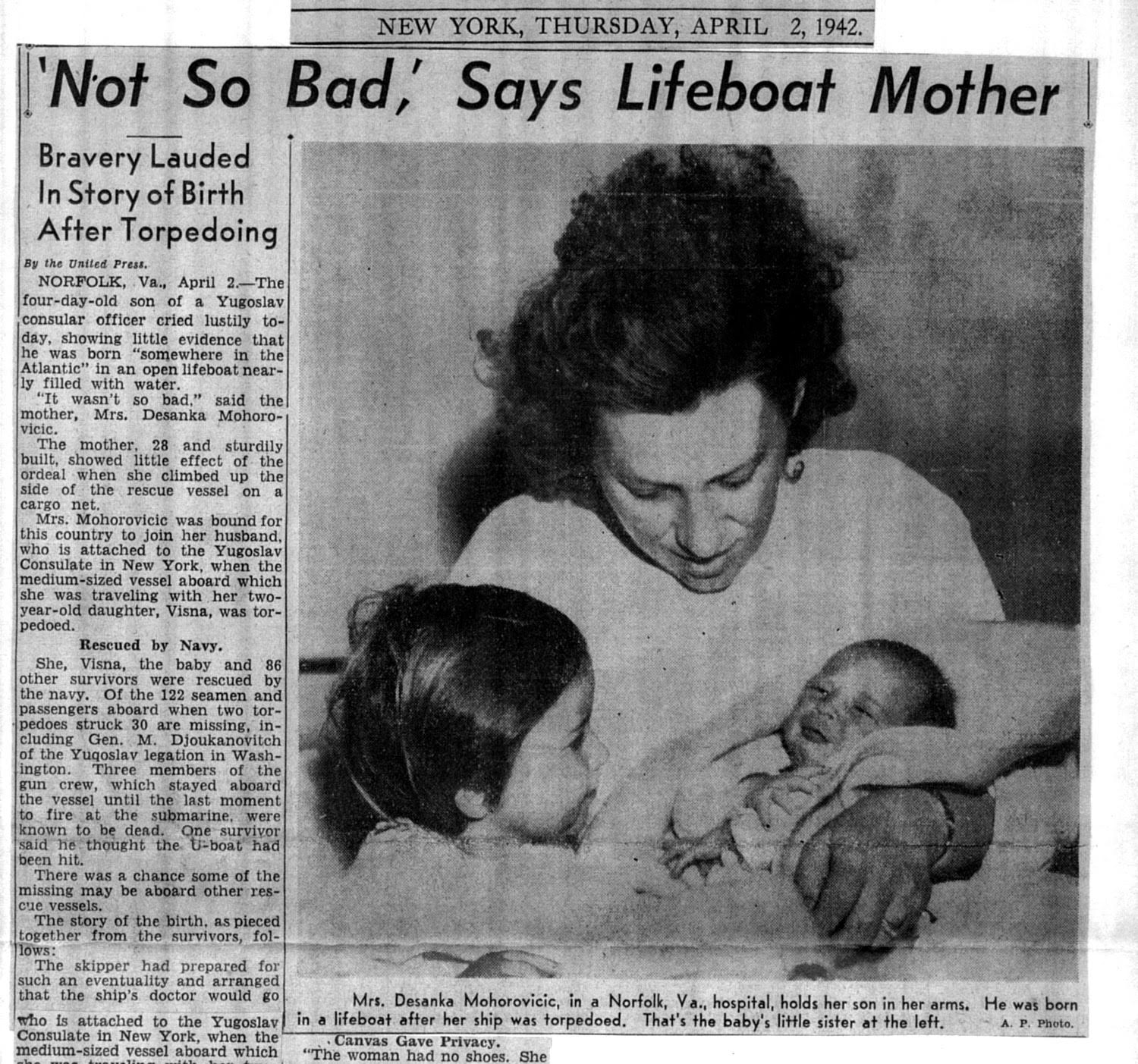

In just half a year, 397 ships were sunk. Nearly 5,000 people, including many civilians, were burned to death, crushed, drowned or vanished into the sea. But in a remarkable twist of fate that helped in a small way to alter the course of the war, a child was born in a lifeboat east of Cape Hatteras.

________________________

On Palm Sunday, March 29, 1942, a blond, blue-eyed Yugoslavian woman traveling from South Africa had been counting down the days until she would reunite with her husband, a diplomat in exile at New York — only one day to go. Months earlier, the family escaped from their homeland amid the chaos unleashed by Hitler’s invading army but they became separated along the way.

She was 28 and had her 2-year-old daughter by her side. She was also eight-and-a-half months pregnant. And she suddenly began to go into labor.

She was 28 and had her 2-year-old daughter by her side. She was also eight-and-a-half months pregnant. And she suddenly began to go into labor.

If the world was not challenging enough for Desanka Mohorovicic, she was also surrounded by 19 strangers in a lifeboat in near total darkness in the middle of the night, 40 miles east of Cape Hatteras, pitching and plunging in 15-foot seas, soaking wet and chilled to the bone by 25-knot winds and 50-degree temperatures. Sharks patiently circled their lifeboat. And they were in the Gulf Stream, helplessly being swept out into the lonely abyss of the deep Atlantic.

Supporter Spotlight

One thing buoyed her spirits, that she would somehow survive her ordeal: her faith in God.

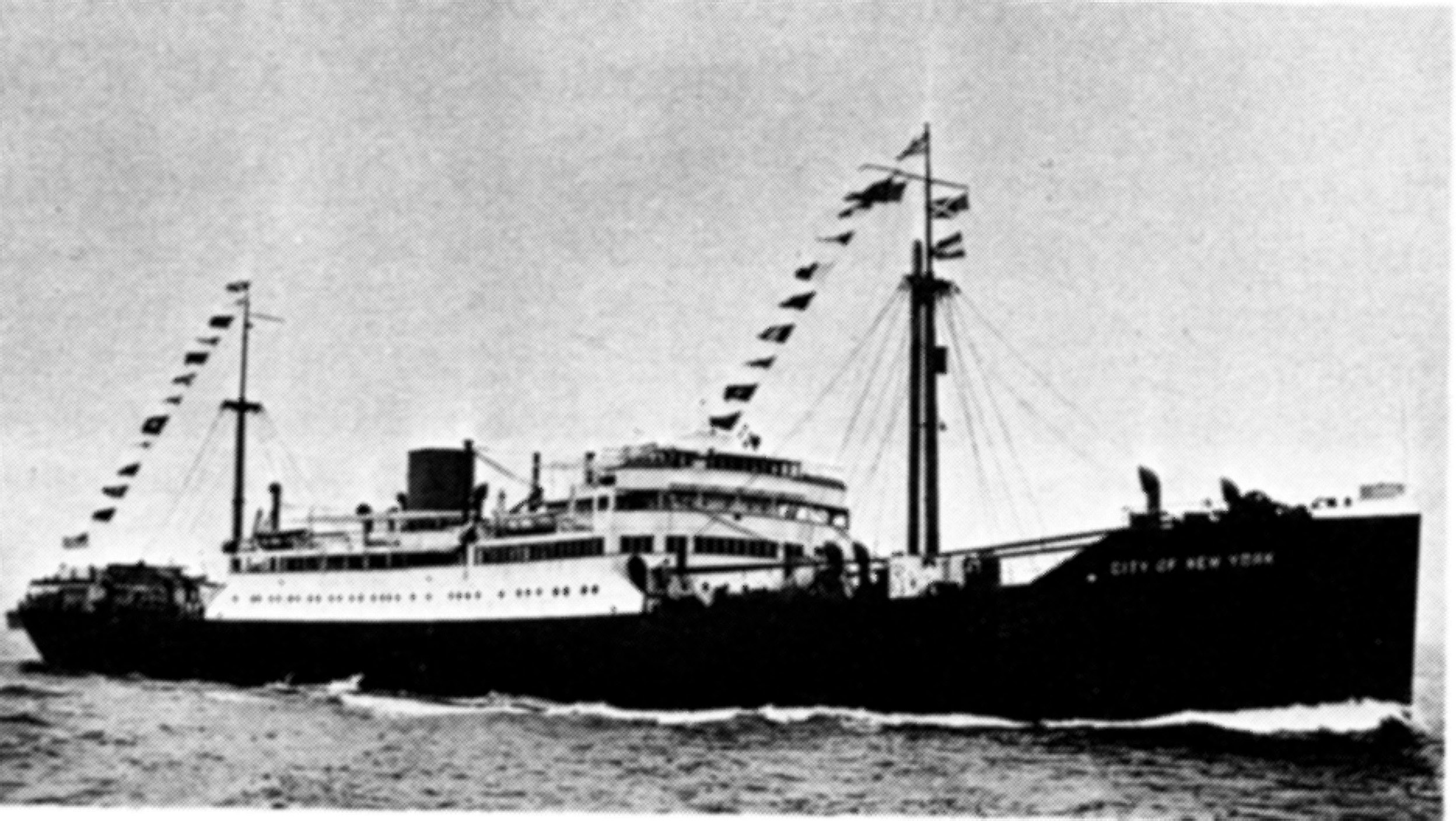

Twelve hours earlier, Desanka had been warm and dry aboard the 452-foot-long passenger-freighter, the City of New York, inbound to the United States from Cape Town via Port-of-Spain, Trinidad.

They had traveled 7,600 nautical miles since Cape Town and had 330 miles to go — just 24 hours. But the ship had yet to run the U-boat gauntlet off Cape Hatteras, a heavily traveled ocean passage described by the U.S. Navy in the spring of 1942 as “the most dangerous place for merchant shipping in the world.”

Capt. George T. Sullivan nervously paced the bridge wings as the City of New York knifed her way through choppy seas and a chilly Force 6 wind out of the northwest. His mind was filled with worry for the well-being of his ship’s 47 civilian passengers, 88 crewmembers and nine sailors of the U.S. Navy Armed Guard. He knew that they were entering a deadly war zone of the Second World War.

Approaching North Carolina waters, the ship’s shortwave radio crackled constantly with plaintive Morse code distress calls: “di-di-dit, dah-dah-dah, di-di-dit (SOS);” or, “di-di-dit, di-di-dit, di-di-dit, di-di-dit” (SSSS—attacked by submarine).

During the preceding two weeks in March, such signals were broadcast two to three times a day or more along the approaches to Cape Fear, Cape Lookout and Cape Hatteras, as Allied ships were being sunk by German U-boats. Off the North Carolina coast, 31 ships and 683 people perished in just 16 days.

The period was the darkest, most desperate and most heart-rending for the U.S. government — Washington military and political leaders faced a dire lack of anti-submarine patrol vessels and vast disagreements as to how merchant sailors should best be protected.

None of that mattered to Desanka Mohorovicic. She just wanted to be in her husband’s embrace.

As the City of New York approached Cape Hatteras at midday March 29, Desanka and her daughter attended Palm Sunday services on the foredeck of the ship. Not far away, Capt. Sullivan whispered something in the ear of the ship’s physician while pointing at the pregnant woman. The doctor nodded.

Meanwhile, passengers returned to their cabins while others strolled about the main deck awaiting the clanging of the lunch bell. A few children played a game of chase as their parents enjoyed the warmth of the sun. High above, a crewman in the crow’s nest on the forward mast vigilantly scanned the horizon. On the aft deck, two sleep-deprived sailors of the U.S. Navy Armed Guard stood near the ship’s 4-inch gun.

At 12:45 p.m., the lookout in the crow’s nest screamed, “Torpedo! Port side!”

One second later, the waterborne missile tore into the No. 3 hold directly beneath the bridge, blasting a gaping hole below the waterline. All electronic communications aboard the ship were disrupted, and the captain was unable to receive damage reports or to dispatch emergency orders.

Instinctively, and as a result of weeks of training, the helmsman rounded the ship into the northwest wind, the engineer shut down the engines, and crew members raced to their lifeboat stations. The telegraphist in the radio room frantically tapped out SSSS, SSSS, SSSS.

Within a frightfully fast 10 minutes, the entire ship, bow first, slipped beneath the waves and sank to the bottom of the ocean 6,000 feet below.

Lowering a lifeboat was typically a dangerous and delicate operation in the best of conditions but doing so from a steeply listing ship in strong winds and choppy seas was an enormous test of skill and composure.

As American passenger Sarah King’s lifeboat, descended on the falls, a second torpedo slammed into the ship just 20 feet away. The lifeboat fell rapidly downward as a 30-foot “great geyser of water” rained down upon King and the other occupants of the lifeboat.

“We braced ourselves as it came,” King said. “We were driven down into the water. As I went down, I wondered if this was really the end.”

Desanka and her daughter grabbed some woolen blankets from their cabin and were climbing the companionway leading to the upper deck when the second torpedo struck. Mohorovicic slipped and tumbled down the stairs. She got up off the deck and pulled herself up the stairway, her legs badly scraped and bruised.

Soon after emerging onto the lifeboat deck, she was greeted by the ship’s doctor, Leonard Conly, who previously had been asked by the captain to be sure to locate and stay with the pregnant woman if they would have to abandon ship. Sullivan had clearly planned ahead and expected the worst.

Conly rushed Mohorovicic and her daughter to lifeboat No. 4, which they boarded along with 19 others. By now, as the ship was slipping ever faster to her watery grave, composure gave way to disorder and chaos.

As Conly hurried to board the descending lifeboat swaying wildly alongside the stricken ship, he slipped and fell, breaking two of his ribs. Now it was the doctor who needed medical attention, but aboard the lifeboat there was only a basic emergency first-aid kit: some bandages, gauze and disinfectant, but no instruments and no anesthesia.

Charles Van Gorden had been a junior officer aboard his ship; now he commanded his own vessel, Lifeboat No. 4. Aboard his boat were a Jewish couple who months earlier abandoned their German home for the safety of America. They were now probably thinking that escaping the Nazis was becoming exceedingly difficult.

Near them sat 14 others from various nations, including the expectant mother. Not all were fluent in English. Desanka spoke Serbian and some French but little English. Most of the survivors were too stunned or scared to say anything anyway.

Van Gorden organized the merchant crewmen aboard the lifeboat, and pairs began taking turns pulling on the oars. Their first objective was to get themselves away from the sinking ship and its dangerous debris field.

Van Gorden also hoped to reach those survivors not in lifeboats and soon encountered an overcrowded raft containing Sarah King. She had, so far, survived the calamity. King, and a father with his 8-year-old daughter were transferred to the lifeboat.

When the ship disappeared into the depths, bobbing on the surface amidst wreckage and oil were four crowded lifeboats and a half dozen or so rafts,126 people in all. Eighteen souls went down with the ship.

Due to the variability of the wind and waves and the eddies of the Gulf Stream, the City of New York’s lifeboats and life rafts soon drifted apart and went their separate ways.

Most everyone clung to the hope that they would soon be rescued. After all, the telegraphist had broadcast the ship’s coordinates at the moment it had been torpedoed. Hours later, however, the survivors were scattered across a wide swath of ocean many miles to the northeast. Back at the site of the attack, not a single vestige of the disaster remained for would-be rescuers to find.

Aboard Lifeboat No. 4, the barefoot Desanka and her daughter Vesna huddled together on a portside bench near the middle of the little boat, shivering in the cold. The City of New York’s crew members glanced at one another and silently communicated their concern about the young mother.

Then, the unimaginable happened. Desanka felt her first contractions. Quietly, she whispered prayers in Serbian for her baby to wait but it seemed determined to be born. She did her best to hide her discomfort.

By 8 p.m., as the wind strengthened and the spindrift of breaking waves whipped through the air, it was no longer possible for her to hide that fact that she was having her baby. It came as little surprise to Dr. Conly, who fully expected the violent motion of the lifeboat to induce the woman’s labor.

A crewman helped Conly arrange a section of canvas sail to help provide a little privacy for the shy young mother as she was about to give birth in the presence of 19 strangers in close quarters.

“The sea was rough,” the crewman later said. “By the time her labor pains began, the boat was practically full of water. The woman had no shoes. She did not complain and did everything she could to make it as easy as possible for the doctor and those who attended.”

Neither did Conly complain, although he winced in pain on almost every lurch of the lifeboat. The physician wished he had more to work with aboard his waterlogged maternity ward than what was in the basic emergency lifeboat kit: hemostats, scissors, gauze, iodine, aspirin, all drenched in salt water.

The delivery would have been no easier if conducted on a roller coaster on a rainy dark night. On his knees, it was impossible for the doctor to see beneath the canvas sail; he could hardly keep from being tossed out of the lifeboat. The best he could hope for was to be ready to receive the newborn at the moment of delivery, which happened at about 2:30 a.m. on Monday when Desanka Mohorovicic gave birth to a healthy, 8-pound baby boy.

Now there were 22 souls in the lifeboat. They were 40 miles from Hatteras Island and getting farther from land by the hour. Many times in the war zone off the Outer Banks survivors in lifeboats or rafts from torpedoed ships were never seen again.

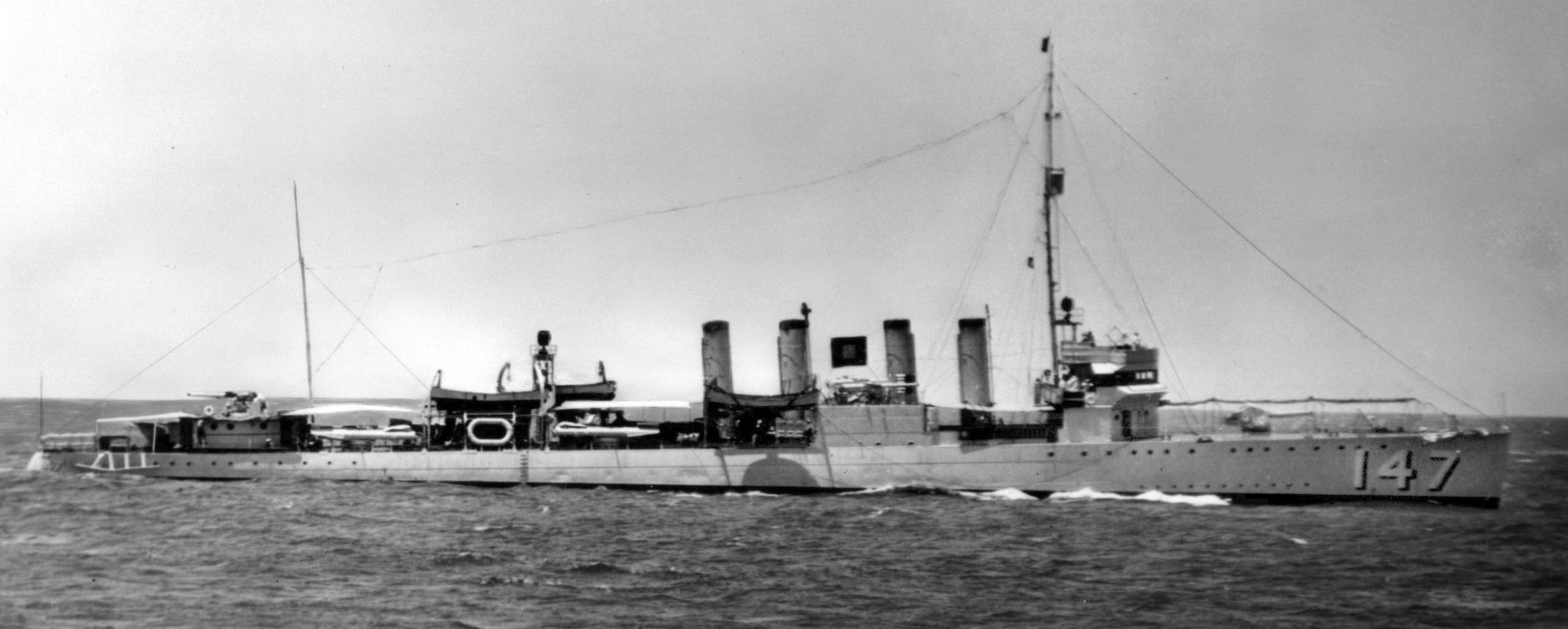

Meanwhile, the World War I-era Wickes-class naval destroyer USS Jesse Roper had been patrolling the waters off the Outer Banks on anti-submarine patrol. During the preceding weeks in March, the warship had been constantly responding to distress calls but only finding oil slicks, debris and empty lifeboats. Depth charges were dropped on sonar contacts day and night depriving the destroyer’s officers and crew much needed sleep.

“We would see partial wrecks, the debris floating everywhere, the oil slicks …,” recalled Boatswain’s Mate 2nd Class radioman Rhodes Chamberlin when I interviewed him at his home in El Paso in 2001. “We were on this ‘finding a needle in a haystack’ situation, looking for submarines by ourselves, and, considering the number of square miles that are out there in the ocean, (the U-boats) really were a needle in the haystack.”

“Ping … Ping … Ping …,” bleated the destroyer’s sonar transmitter as it searched for solid underwater objects and the reflected sound that would be bounced back to the ship’s sonar receiver, much like a lonely songbird calling for companionship.

The sonar operator would suddenly hear a response: “Ping-ping, Ping-ping, Ping-ping!” The klaxon wailed, “ah-wooga, ah-wooga,” calling general quarters.

The ship’s intercom barked commands, men flew into action and a pattern of depth charges were dropped. “Boom, boom, boom.”

Nothing appeared on the surface, no oil nor debris were observed which would have indicated that the Roper had successfully sunk a U-boat. The sonar echoes fell silent. The contact was lost. The off-duty sailors climbed back in their bunks, unable to go back to sleep.

Morale aboard the destroyer was about as low as it could get.

During the early morning hours of Tuesday, March 31, the Roper was patrolling in water 11,000 feet deep, east-northeast of Cape Hatteras, near the axis of the Gulf Stream. Visibility was 20 miles, although, as was typical, a shallow, intermittent cloud of fog hovered over the warm Gulf Stream waters.

The waxing gibbous moon occasionally shone brightly above, illuminating tatters of stratus clouds streaming in from the west. Occasional flashes of lightening appeared from the direction of the mainland. It seemed an idyllic night to be at sea — unless you were in a lifeboat.

At 4:28 a.m., a brilliant light shot into the night sky, about 8 miles due north of the Roper’s position. The officer of the deck ordered the destroyer to rush to the signal flare’s source. There they found a lifeboat with 21 survivors from the City of New York, plus one additional person who had joined the others in the lifeboat, Desanka Mohorovicic’s 26-hour-old son.

A cargo net was draped over the gunwale of the Roper, and men began to leap out of the lifeboat, timing their jumps as the lifeboat was lifted on the waves.

“Send the baby up next,” someone in the lifeboat shouted. The mother, however, was not so eager to hand her newborn to strangers on a strange ship in total darkness. Making matters more worrisome, the lifeboat pitched and yawed, and the gap to the destroyer’s hull rapidly widened, then narrowed. “What if they drop him?” she must have thought. But her moment of indecision was brief.

“Then they took the baby up, it had no clothes, and I was afraid they would drop it,” said Sarah King.

Many years later, when she told her amazing story, Desanka Mohorovicic’s most vivid memory was the look on the young sailor’s face when he realized he had been handed a newborn. The baby was immediately rushed to the Roper’s sickbay. Even before he arrived there, word of his rescue began to quickly make its way through the ship.

“It was a big deal,” remembered Chamberlin. “Just talking about the fact that it was a newborn baby — everybody wanted to see it.”

Sailors who previously had been sullen and fatigued from fruitless hours of patrolling “Torpedo Junction,” from the incessant wailing of the klaxon punctuated by exploding depth charges, from days of feeling impotent and vulnerable, were suddenly inspired by the unmistakable looks of gratitude on the faces of the survivors.

According to the New York World-Telegram, after learning of the name of the American warship that had rescued her young family, Desanka proudly announced with a few words of English that her baby would thenceforth be named Jesse Roper Mohorovicic.

At 10:55 p.m., the destroyer tied up to the south side of Pier No. 5 at Norfolk Naval Operating Base. A large crowd had been awaiting the arrival of the destroyer, and Naval officers, reservists, Red Cross nurses and military photographers cheerily greeted the disembarking passengers. Flash bulbs popped one after another. A blue-eyed nurse was photographed holding baby Jesse Roper, warmly swaddled in a blanket, his head barely visible in the photo.

Two weeks later, with their morale and fighting spirit bolstered by the rescue of the survivors from the City of New York and the baby named for their destroyer, the crew of the USS Jesse Roper sank the U-85 southeast of Nags Head, the first U-boat to be destroyed in U.S. waters in the war. The Roper’s victory marked the beginning of the end of what became known as “Torpedo Junction.”

In January 2001, I located and contacted Jesse Roper Mohorovic — the family dropped the “ic” at the end of their surname to make it easier to pronounce — and asked him if I could interview him for a documentary film that I was producing titled, “War Zone—World War II Off North Carolina’s Outer Banks.”

Initially, Jesse declined, saying that there wasn’t much he could say since he obviously didn’t remember his birth in the lifeboat. “Well, I had really hoped to learn a little bit more about your mother, what was she like?” I asked, just before Mohorovic was about to say goodbye. “Okay,” he said, “Come to my office in Richmond, and I’ll chat with you.”

We agreed that he would answer in the third person, as someone who knew Desanka Mohorovicic. He did not want to necessarily identify himself as her son, “the lifeboat baby,” “the son of Neptune,” or “the baby Hitler couldn’t get,” as the national press referred to him in 1942. There were more important things, other than himself, that he wished to share.

“She was a woman of very strong faith, very, very strong faith,” Mohorovic said, after describing the events leading up to the baby’s birth. “And a courageous woman, obviously. And a woman who had great trust that her daughter, her newborn son, would somehow come out of it. She really put her trust in God —maybe not so commonly heard today, but that was her view.”

Mohorovic took a deep breath and sighed. He seemed to want to say something more. He seemed momentarily uncomfortable telling the story in the third person, unwilling to be disassociated from the remarkable woman, Desanka Mohorovicic. Then, he looked directly into the lens of the TV camera and said, “Well, Mrs. Mohorovicic was my mother. And she passed on in 1993, and I loved her like every son loves their mother.”

Kevin Duffus is the author of six books spanning 500 years North Carolina’s incomparable maritime history, including :War Zone—World War II Off the North Carolina Coast.” He was named “2014 North Carolina Historian of the Year” by the North Carolina Society of Historians.