The electric power sector is changing, and North Carolina is in the position to shift to cleaner, cost-effective energy production that can reduce pollution, according to a report released earlier this month.

Prompted by the North Carolina Clean Energy Plan, the report, Power Sector Carbon Reduction: An Evaluation of Policies for North Carolina, is the study of carbon reduction policies for the state’s power sector.

Prompted by the North Carolina Clean Energy Plan, the report, Power Sector Carbon Reduction: An Evaluation of Policies for North Carolina, is the study of carbon reduction policies for the state’s power sector.

Supporter Spotlight

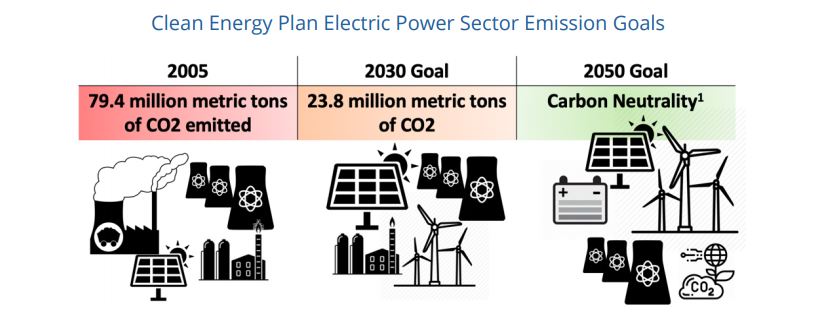

Under Gov. Roy Cooper’s Executive Order No. 80 signed October 2018, the Clean Energy Plan, or CEP, — the state’s plan to reduce the amount of carbon pollution from the electricity generated and used released September 2019 — sets for the state a goal of 70% reduction compared to 2005 carbon dioxide, or CO2, emissions levels by 2030, and reach carbon neutrality by 2050. These targets include emissions from in-state electricity generation and electricity imports, according to the report.

“Well-designed policies can accelerate pollution reduction, make change more affordable for state residents and business, and stimulate job growth,” which is why the clean energy plan recommended the power sector study, according to the document.

The state Department of Environmental Quality approached researchers at Duke University Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions and the University of North Carolina’s Center for Climate, Energy, Environment and Economics to conduct the study.

Kate Konschnik, director of the Climate and Energy Program at the Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions at Duke University, led the research.

She told Coastal Review Online that the one takeaway from the report is, “How we make and use electricity is changing, and with that change comes an enormous opportunity to shift into cleaner sources of power, to protect our watersheds, air quality and public health. I hope the report conveys that we have options at this moment – there is no one cost-effective way to reduce pollution from the electric power sector.”

Supporter Spotlight

The state has options for meeting the CO2 reduction targets detailed in the clean energy plan. With the rapid shifts happening on the grid and the merging of cost between types of electricity generation, “even modest policies could drive large changes in the North Carolina power sector, with positive emissions and economic impacts,” according to the report. The report does not make specific recommendations but does outline different policies and offers options for decarbonizing the grid.

Past state air quality and clean energy policies as well as climate policies implemented in other states were studied to refine the list of policies to study. Then, the policies were run through two power-sector capacity planning models to compare cost, emissions and energy mix outcomes.

Konschnik explained that the power sector in this case means the electric utility industry, or “the power plants and the wires that deliver power to our homes and businesses.”

Since the carbon pollution goals in the state Clean Energy Plan relate to the electricity used in the state, “I suppose we mean, how do we cut pollution from the power plants that are located in North Carolina or that serve us from across state lines?” Konschnik added.

The state Clean Energy Plan proposed four potential policy pathways to achieve its targets: accelerated coal retirements; market-based policies that put downward pressure on CO2 emissions from the power sector; clean energy policies; and combinations of these policies.

The power sector policies study used these pathways as a launching point and defined specific policies to study for possible use.

“The electricity system appears to be at a ‘tipping point’ where small changes in gas prices or renewables costs can sway the balance between new capacity (i.e., gas turbines, renewables, and battery installations),” the report lists as the first key finding.

The report also finds that CO2 emissions from the state’s electric power sector will continue to decline as coal plants are retired, though new policies are needed to reach the Clean Energy Plan’s targets.

“If carefully designed, these policies can make emissions reductions more cost-effective and affordable, and drive positive economic development across the state,” the report states.

A third key finding is that coal retirement, carbon market and what’s known as carbon adder policies achieve reductions by lowering in-state fossil fuel generation, while clean energy standard policies increase in-state renewable generation, pulling in new resources to the grid. A combination of these policies can accomplish both outcomes more efficiently. Carbon adders are a market-based policy that account for the costs to society imposed by a power plant that emits CO2 that are not paid by the utility but used in the decision-making process.

Konschnik said in an interview that in recent years, a lot of aging coal-fired power plants have been retired in North Carolina and around the country.

“Utilities are making decisions about what to build in their place — decisions that will stay with us for 30 to 50 years. Public policy can help prioritize cleaner substitutes while ensuring affordable bills and a reliable system that works when you need it,” she explained.

Another key finding is that offshore wind requirements are projected to increase the cost of clean energy standards but could drive economic development in supply chains and maritime trades. Economic opportunities related to offshore wind were not studied for this report. However, another recent study projects nearly $100 billion in economic value for North Carolina, based on forecasts of East Coast offshore wind installed capacity.

The power sector report also finds that some policies can achieve significant reductions in local air pollutants, including coal retirements or clean energy standards combined with another market-based policy studied in the report, joining a carbon market like the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, or RGGI, or other policies. Each state that participates in the RGGI market sets a budget of CO2 allowances that shrink every year.

The Environmental Defense Fund supports the state joining RGGI. RGGI is the first mandatory market-based program in the United States to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, a cooperative effort off Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont and Virginia to cap and reduce CO2 emissions from the power sector, according to RGGI’s website.

“The evidence presented in the Clean Energy Plan is clear: North Carolina can make critical progress on its climate goals by joining RGGI. Governor Cooper should act on these strong findings to move the state toward a clean energy future, while seizing meaningful opportunities to improve health and equity across the state,” said David Kelly, Senior Manager for North Carolina Political Affairs at EDF, in a statement.

Drew Stilson, policy analyst for Environmental Defense Fund, said that by placing a declining limit on carbon emissions from the power sector through RGGI, the state can guarantee that emissions fall on a timeline consistent with the state’s climate goals.

“RGGI is designed with the flexibility to implement it in a way that makes the most sense for the state’s unique needs, and it’s highly compatible with a variety of other complementary clean energy policies in order to maximize the environmental and economic benefits for North Carolina,” he continued.

Policies that achieve the 2030 Clean Energy Plan target in at least one of the models include: carbon adders on generation; clean energy standards, with or without an offshore wind requirement; and combination policies that start with clean energy standards and also include either accelerated coal retirements, RGGI, or a carbon adder, according to a clean energy fact sheet.

Konschnik said the group studied how policies might result in different levels of air pollution but one type of data that they did not get to publish in the report, though they hope to on the website, is the effect of different climate and clean energy policies on mercury pollution from coal-fired power plants.

“In most cases the policies reduced mercury emissions by tons per year over business as usual – but some worked faster than others to get this neurotoxin out of the air,” she said. “One modeling run showed that if we increase our use of electricity in North Carolina without policies to clean up our power plants, we might run the risk of increasing mercury emissions.”

In a few instances, the group considered policies that might generate revenue for coastal resilience and storm recovery. “Specifically, by joining a regional ‘carbon market’ where utilities buy and sell allowances to emit carbon pollution, North Carolina could generate nearly $1 billion over the next 10 years,” Konschnik said.

Other states that participate in RGGI use the resulting funds for these types of projects, as well as energy efficiency and residential bill assistance.

“We also mention that Clean Energy Standards could include a fee system where a utility would pay into a fund if they were otherwise unable to meet the required amount of clean energy on their system – and those funds could also be used for coastal resilience projects,” she said.

Konschnik told Coastal Review she was excited to lead the research. “It was intellectually challenging and a lot of fun.”

She said the researchers worked with a group of North Carolina stakeholders who represented the views of their constituencies while also coming to the table with open minds.

“Together we studied what other states have done, and what North Carolina has done in the past to encourage clean energy and create jobs while improving air quality,” she said, adding that the team then defined specific policies to model and study and discussed key values such as affordability and equity.

Gudrun Thompson, senior attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center, pointed out the basketball rivalry between the two universities didn’t interfere on their work.

“They may be rivals on the basketball court, but this report shows that even during March Madness, there is one thing that Duke and UNC can agree on: limiting carbon pollution from power plants and joining other states in a cooperative effort is an effective—and cost-effective—way to reduce carbon pollution from power plants in North Carolina,” said Thompson. “It’s a slam dunk.”