The Tillett Cemetery is on a low ridge next to Old Nags Head Woods Road in Kill Devil Hills. There’s a chain-link fence around it, but it’s a beautiful setting, surrounded by pine and live oak. The land from the cemetery to Roanoke Sound is now part of Nags Head Woods, but at one time it was a thriving farm.

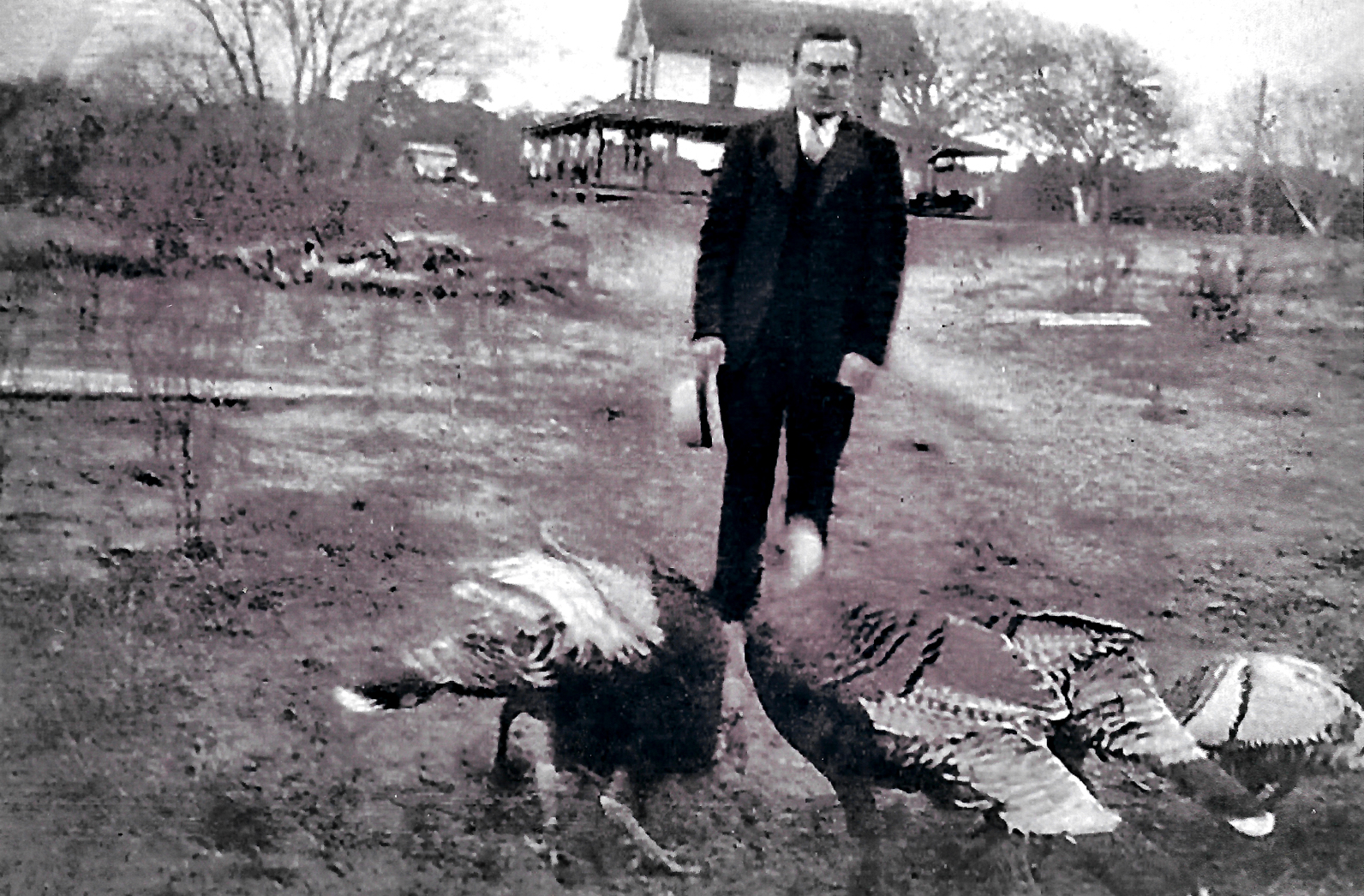

Rad Tillett has taken on the task of tending to the cemetery. He’s 84 and has lived on the Outer Banks his whole life. His grandfather, Isaac E. Tillett—“Mr. Erb”— who was born in 1865, had farmed the land and raised a family with his wife, Maggie S. Tillett. Maggie lived from 1874-1953.

Supporter Spotlight

Rad then pointed to a heavily worn headstone with the dates 1762-1829. “This one here, it’s Thomas Tillett. He started the whole thing,” he said recently.

He then pointed to the headstone next to it.

“This was his wife. She was an Indian. Most of us around here have some Indian blood in us,” he said.

Rad’s grandfather, Isaac Tillett, died in 1948. He has five years of good memories of the farm and his grandparents, he said.

The cemetery holds numerous tales, but some might be difficult to prove.

Supporter Spotlight

There’s Capt. Samuel Tillett, the son of Thomas, who was in the Caribbean when he contracted yellow fever. Realizing he might die, the captain gave instructions on how his body was to be sent home.

“He was supposed to be brought back in a casket filled up with rum,” Rad said.

But then there’s another Isaac Tillett, “who departed this life” Nov. 3, 1851, who shares the name but probably isn’t Rad’s close kin.

“It don’t belong here,” Rad said of the the headstone, explaining that his cousin, Norris Austin, had added it while building the fence around the graveyard.

“This lady up in Currituck … told him (the headstone) was in the trash pile up there. He went and got it. He didn’t know if we were kin to him or what, so he put it here,” he said.

Roanoke Trail

The Roanoke Trail in Nags Head Woods cuts through the heart of the Tillett land.

The trail is a wide, packed-earth path beneath towering pine and hardwood trees. The trail feels like it’s been in place for some time, but Rad has different memories. Pointing to the cemetery, he said that people coming from the north — Kitty Hawk or Kill Devil Hills — would have taken a lane that passed behind the cemetery. From the south, there was another lane that accessed the property off Old Nags Head Road.

But the biggest change, Rad said, are the trees.

“It was all open,” he said. “These trees weren’t here when I was little. People won’t believe that. I can’t hardly believe it myself.”

“It was good farmland. They raised everything — butchered the cows and pigs, salted a lot of it and then smoked it. They had a smokehouse,” he remembered.

There were also sheep at one time, and chickens, ducks and geese. He pointed to a low, heavily forested rise.

“This whole place would be pasture. It went 5 acres down to the water. When I come along, he just had two cows and a bull, just a little to keep him going. He’d kill one in the fall. He’d sell that,” he said.

Mr. Erb didn’t have much choice in selling the meat, Rad noted.

“He didn’t have a refrigerator. He didn’t have power back here. I don’t know how he did it,” he said.

According to Rad, no one back in Nags Head Woods had power. He tells the story of a house his father Herman Tillett, who was a contractor, built a little after his grandfather died.

“My daddy built a house back here back in 1950, right on the water. Put a Delco (generator) back there,” he said.

He pointed to the other side of the trail, where at one time there had been a fence. That was where the produce was grown.

“It’s not high. It’s good land,” Rad said. “He grew corn, potatoes, carrots — just about everything.”

The potatoes were the cash crop.

“My daddy and I dug potatoes,” he recalled.

And, as tourism became more a part of the Outer Banks economy, Rad’s grandfather would make the trip into town.

“When Nags Head picked up, they started building houses on the ocean. He’d go down there with a horse and cart with vegetables all summer. He’d raise them here, take them down there,” he said. “He didn’t drive. My grandmother drove. Just the horse and cart — my granddaddy never did drive.”

The corner of the Tillett house is marked by perhaps a half-dozen of the original bricks. It was a fairly large house; it had to be to accommodate the size of the family.

“They had 12 (children), but two of them died. They raised 10. And then he had one son that was older that my grandma looked after. He was born before my granddaddy got married. That wasn’t supposed to be told. But that was the way it was,” Rad said about his grandparents.

There were two hand pumps for water, “One in the kitchen, the other on the porch.”

Rad walked around to what would have been the kitchen.

“The kitchen was in back of the house — separate,” he said.

He walked around to the other side of the house and pointed to a pit in the ground overgrown with vines.

“That hole, there, that was a dugout potato house with sides on it, put down in the ground about 4 feet. It had a sharp roof on it. They put straw on the roof. They put potatoes and stuff in it in the winter. It wouldn’t freeze,” he said.

At one time, there was a barn across from what is now the Roanoke Trail, although all evidence of the barn is gone. Rad pointed to the faintest indentations visible in the undergrowth, saying that was the road from the house to the barn.

There is, though, better proof that the road existed. About 200 yards past the house, there’s an open marsh with a wooden bridge crossing it. North of the bridge there is a line of low trees that seems out of place in the marsh.

“See where those little trees (are) across there in a line? That was the road. I know he put that in there with just his cart and sand. It would get back there from the pigpen to the water. The barn was just a little bit farther,” Rad said.

The road leads to a huge live oak that historians have said was used to drain the blood from an animal after it had been slaughtered.

“All you do is run line over the (tree) limb and just hang it there,” he said.

Rad never saw the oak tree used – instead, he recalled a “big straight tree with straight limbs” close to the house. But he has not been able to find that tree again.

Roanoke Sound is just a short walk past the live oak. The shoreline is marked by soft white sand. The shallows are marked by leafless trees, bleached almost white by the sun.

“This was right different. That white sand went all the way out there. You can see the trees have died. There was more oak here,” Rad said. “When I was little, it was 60 feet or 50 feet farther. And white sand. Oh it was a nice one, a nice beach.”

Rad’s granddaddy passed away in 1948, his wife five years later, and the property was sold.

“The people who bought it, they were cousins, I think. They lived in Coinjock,” he said. “They just thought they’d have a summer home.”

But vandals broke into the house and ultimately burned it down.

“This was just such a shame,” Rad said.

In 1974, Nags Head Woods was designated a National Natural Landmark, and The Nature Conservancy took over management of the land, which Rad said has worked out well.

“The Nature Conservancy, I think they’re doing a pretty good job,” he said.