“I WAS born a slave; but I never knew it till six years of happy childhood had passed away,” Harriet Jacobs writes in her 1861 autobiography, “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.”

Jacobs was born in 1813 in Edenton to Elijah and Delilah Jacobs, two slaves owned by different families.

Supporter Spotlight

At 6 years old, after her mother passed away, Jacobs lived with Margaret Horniblow, her mother’s mistress. Horniblow taught Jacobs how to read and write, among other skills, and when Horniblow died in 1825, Jacobs was given to the woman’s niece, 3-year-old Mary Matilda.

Charles Martin Boyette, who has been for 14 years an historic interpreter at the Historic Edenton State Historic Site, finds Jacobs’ story remarkable.

“The story of Harriet Jacobs is full of many surprises from a modern perspective,” he said, “but to me the most noticeable was the way that Harriet and her family managed to exercise personal agency even with the constraints of slavery.”

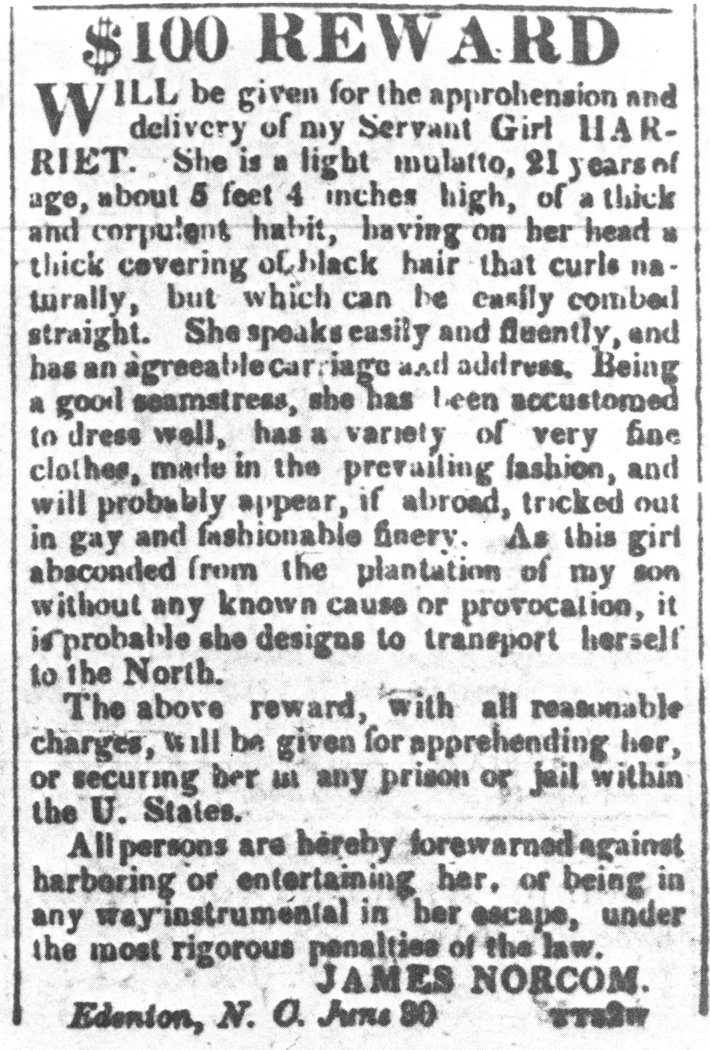

Mary Matilda’s father, Dr. James Norcom, took both Jacobs and her brother John in to live with the family, and soon began making sexual advances toward Jacobs.

“Women are considered of no value, unless they continually increase their owner’s stock,” she writes. “They are put on a par with animals.”

Supporter Spotlight

She started a relationship and had two children with white lawyer Samuel Tredwell Sawyer, and after denying Norcom’s advances multiple times, Jacobs was sent to work on a plantation. She writes that her children were her main reason for living, and when she learned that they would be sent to become plantation slaves as well, she decided to escape to the North to spare them.

“To me, her book is one of the first that openly details the abuse that enslaved women faced from male slave owners,” Boyette said. “Female slaves, as is shown by the treatment Harriet received, were vulnerable to abuse by male slave owners with little recourse in many cases. Harriet put a stop to it in a definitive way by removing herself from the situation through making her way to freedom.”

Jacobs hid in friends’ homes and finally in a garret above her grandmother’s storeroom that was only 9 feet long by 7 feet wide by, at most, 3 feet tall, where she remained for seven years until she could find opportunity to escape. During that time, her children never knew she was there.

“At times, I was stupefied and listless,” she writes, “at other times I became very impatient to know when these dark years would end, and I should again be allowed to feel the sunshine, and breathe the pure air.”

Boyette said he understands that she hid in the attic space during the day when people in town were moving about and likely came out at night for limited periods.

“I am sure when she did come out the doors to the house were locked and the windows covered to protect her anonymity,” Boyette said.

Because the historic site does not have any photos of the house, interpreters base their descriptions of the garret on her writing.

“The space she was hiding in was the small space over the porch similar to a crawl space in a home today,” he said. “Architecturally, you could say the house likely had what we would call a bungalow style roof that extended over the front door as a porch cover. The area (where) she hid would be something like hiding in the eaves of a roof space.”

The secrecy was clearly difficult for Jacobs.

“Season after season, year after year, I peeped at my children’s faces, and heard their sweet voices, with a heart yearning all the while to say, “Your mother is here,” Jacobs writes. She finally did reveal herself to her children before they were separated.

In 1842, after nearly a decade in hiding, Jacobs finally had the opportunity to escape from North Carolina and boarded a ship in Edenton that took her to Philadelphia. She was reunited with her brother and her daughter Louisa Matilda, and later her son Joseph.

Jacobs published “Incidents” 16 years after Frederick Douglass published his 1845 autobiography, “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave.” Although their experiences differed, and his book received immediate acclaim while Jacobs’ did not, many point out similarities.

“As regards the Frederick Douglass comparison, I will say that their lives had considerable parallels,” Boyette said. “Her description of slavery from an enslaved woman’s perspective did much to reveal a part of slavery that did not receive as much focus during that period.”

“As regards the Frederick Douglass comparison, I will say that their lives had considerable parallels,” Boyette said. “Her description of slavery from an enslaved woman’s perspective did much to reveal a part of slavery that did not receive as much focus during that period.”

“Incidents” was considered a work of fiction until the archival work of Jean Fagan Yellin in the 1970s and 1980s proved otherwise. Yellin published “Harriet Jacobs: A Life” in 2004.

“Many people know the general story of her life as far as escaping slavery and writing her book,” Boyette said, “but many do not realize after the Civil War she was active as a social activist, furthering the interests of African Americans in the post-Civil War period.”

According to the digital publishing initiative, Documenting the American South, Jacobs began to work with relief efforts, from helping former slaves who had become refugees to founding a school with her daughter.

“She acted as an advocate for African American rights in the post-Civil War period,” Boyette said. “In particular, she worked to set up and teach in schools for newly freed people. For a living, she and her daughter ran a boarding house in the Boston area.”

Jacobs opened her boarding house in 1870 and by the 1880s, Jacobs was settled in Washington, D.C., where she died in 1897.

The Historic Edenton State Historic Site offers walking tours, and while the buildings in which Jacobs lived no longer stand, Boyette said that seeing the area where she lived is a powerful thing.

“Being able to walk the streets that Harriet walked and see some of the buildings still standing from her time allows me to create a mental landscape of what life was like for her in Edenton,” Boyette said.

Edenton, North Carolina’s second-oldest town, was also once the state’s second-largest port. According to the Historic Edenton website, the town “provided slaves with a means of escape via the Maritime Underground Railroad before Emancipation.”

The site offers free admission 9 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday and separate guided tours 10 a.m.-4 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday.

“The main concept I want people to take away from her story is an understanding of what life was like for enslaved persons before the Civil War,” Boyette said. “How they used whatever means available to make a life for themselves and their families even with the heavy constraints of slavery.”

Jacobs writes, “It has been painful to me, in many ways, to recall the dreary years I passed in bondage. I would gladly forget them if I could. Yet the retrospection is not altogether without solace; for with those gloomy recollections come tender memories of my good old grandmother, like light, fleecy clouds floating over a dark and troubled sea.”