The Great Gale of 1878 is a largely forgotten storm now, but as it tracked up the Eastern Seaboard in late October it left a path of destruction from North Carolina to New England.

The U.S. Army Signal Corps, with its series of telegraph stations lining the coast, was responsible for tracking tropical storms, and 1878 was a typical year for tropical systems. At the time, the Corps did not name the storms, they were simply assigned numbers.

Supporter Spotlight

There were 12 tropical storms for the year; 10 became hurricanes, but none was as destructive as the 11th tropical system, the Great Gale of 1878.

Taking a path through North Carolina similar to those of hurricanes Hazel in 1954 and Floyd in 1999, the system passed through the state, crossing into Virginia somewhere around the Great Dismal Swamp.

As it roared northward, it created a night of terror for ships sailing North Carolina waters. Perhaps nothing was as grim as the evening of Oct. 22, 1878, and the sinking of the schooner Magnolia as recorded in the 1879 “Report of the Chief Signal Officer to the Secretary of War.”

Written by Army Signal Corps Sgt. W. Dixon, Kitty Hawk, the report offers no embellishments beyond the basic facts, but a tale of the night of terror emerges.

“October 22 to 24 — During the (hurricane warning) display a hurricane was experienced at this station. It began at 6:30 p.m. of the 22nd from the southeast. The wind and rain increased rapidly until 2 a.m. of the 23rd, and the barometer had reached its minimum at that time; actual barometer read 29.064 and the wind velocity reached 88 miles per hour. The wind shifted suddenly from the southeast to southwest, increasing in velocity and carrying away the anemometer. Damages during the storm can be given briefly as follows; Schooner Magnolia, Capt. George Wurtle, was wrecked in Albemarle Sound; vessel total loss; captain drowned. First Lieut. James A. Buchanan, acting signal-officer and inspector, was a passenger on board on his way south for the purpose of inspecting the signal stations along this coast and was saved by lashing himself to the gunwale, after the vessel had capsized and was grounded, and swimming ashore.”

Supporter Spotlight

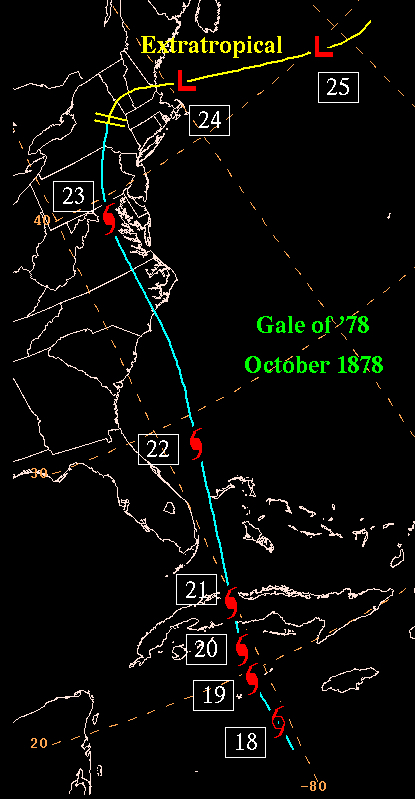

The Great Gale was first recorded as a tropical system Oct. 18, 1878, in Jamaica, although a paper written in 2000 for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Weather Prediction Center indicated the storm probably formed a few days earlier.

“It is hypothesized that a tropical disturbance was present around October 16 in the southwestern Caribbean,” according to the NOAA paper.

The storm moved north, stalling briefly over Cuba, then gathered speed as it passed through the Florida Straits Oct. 21, 1878, before making landfall around 11 p.m. the next day between Bald Head Island and Cape Lookout.

By 1878, the Signal Corps had telegraph lines from Key West to Maine. Its task was to hoist warning flags as storms approached, report the weather conditions and record whatever havoc a storm may create.

Pvt. H.J. Forman’s report from Cape Lookout gives one of the first witness accounts of the storm.

“October 21 to 24 — Heavy rain during storm signal of much benefit to vessels in the harbor and fishermen on the beach. On October 22 steam yacht Florence Witherbee anchored in harbor; on the night of the 23d she parted her chains and had to run ashore to save life; at this time the velocity of the wind was 100 miles per hour. The same night the schooner Wyoming was dismasted and driven ashore 25 miles north of this station; the captain and one consular passenger were washed overboard and lost.”

From the Cape Hatteras Signal Corps office at the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse came the terse report: “Two-masted schooner Altoona, of Boston, cargo, logwood, ran ashore 11:45 p.m. of the 22nd; total loss.” The crew was saved, however.

‘Dangers of the Sea’

Some of the most chilling accounts of the storm came from newspapers, such as the Nov. 1, 1878, New York Times recounting of the rescue of the City of Houston, an iron-hulled steamship designed to haul freight and passengers between New York and Houston that sank near Frying Pan Shoals.

“Dangers of the Sea…An Abandoned Schooner Rescued” the headline reads.

The story begins Sunday, Oct. 20, 1878, when the ship left New York, “and had favorable weather until the following Tuesday, when a heavy gale set in … By 9 0’clock in the evening a leak, which soon became uncontrollable, was sprung and some of the machinery was dibbled.”

By 2 a.m. Oct. 23, the engines were flooded and the passengers told of the danger and at 4 a.m., orders were given for everyone to put on life preservers.

“Signals were burned from the pilot-house, but it was intensely dark and raining heavily, so that no vessel saw them.”

At daybreak “… the steamer was now beginning to sink, and the boats were about to be lowered when the (steamer) Margaret hove in sight.”

By 8 a.m., when the rescue operation began, there was “10 feet of water in the after part of the vessel.” An hour later, passengers and crew were safely aboard the Margaret.

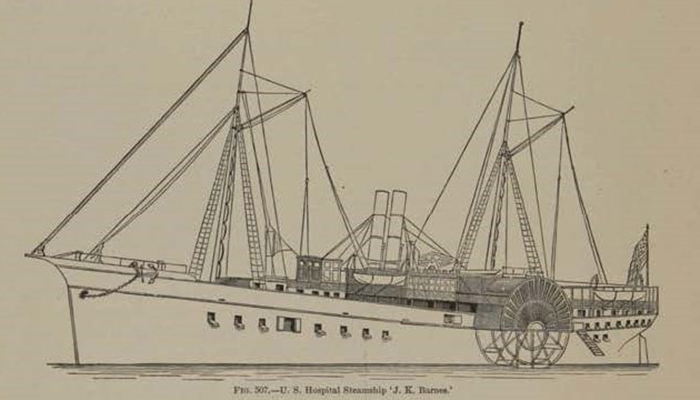

The J.K. Barnes

There was a fourth ship that sank in North Carolina waters during the Great Gale. Launched in 1865, the steamship J.K. Barnes was one of the first purpose-built Army hospital ships in the U.S. fleet. Named after the Surgeon General Joseph K. Barnes, the ship was designed to handle up to 449 wounded soldiers and the medical personnel to care for them. In 1870, it was sold as surplus and renamed the General J.K. Barnes.

The ship foundered Oct. 23 off Cape Hatteras. The crew transferred to a schooner that took them to Charleston, South Carolina.

After North Carolina, Tropical Storm 11 quickly became extratropical but continued north as a powerful storm. According to The Hurricane of October 21-24, 1878, a Delaware Geological Society publication written by Kelvin Ramsey and Marijke J. Reilly in 2002, “Between Philadelphia and Dover on the Delaware River and Bay coast, the storm surge was in the form of a surge wave perhaps as high as 5 to 8 feet above high tide (12 ft above sea level).”

The path of the storm took it slightly west of Philadelphia. It finally curved out to sea near Portland, Maine, where 60 mph winds were reported.

Public pressure for funding

Notable by its absence are reports from the Lifesaving Service, the Coast Guard’s predecessor.

As the Great Gale ravaged the coast, the Lifesaving Service was spread thinly, with no stations south of Chicamacomico in what is now Rodanthe. And on the Outer Banks between False Cape on the north end and Chicamacomico, there were only seven stations.

Two horrific shipwrecks along the Outer Banks in the winter of 1877-78 highlighted the problems that years of inadequate funding for the Lifesaving Service had caused.

In November 1877, the USS Huron ran aground just 200 yards off the Nags Head beach. As waves pounded the ship, the crew waited in vain for the men of the Nags Head Lifesaving Station to rescue them, but the station was closed until December. Of the 132 men on board, only 34 survived.

Two months later, in January 1878, the Metropolis struck a shoal 100 yards from the beach. Jones Hill, now the Currituck Beach Lighthouse, was the nearest lifesaving station, 4 miles away.

Initially, the crew was not aware the Metropolis was in distress. When they finally did arrive, they brought inadequate supplies for the rescue and proved to be poorly trained.

Of the 245 men and women on the ship, 85 perished.

Bowing to public pressure, Congress acted, providing funds to keep lifesaving stations open year-round and adding new stations beyond the seven that existed on the Outer Banks. Beginning in July 1878, when the new fiscal year began, enough money was appropriated to create new stations, hire professional crews and keep stations staffed year-round. There were eventually 29 North Carolina Lifesaving Service Stations.