Reprinted from Port City Daily

Preliminary data released last month by scientists at seven North Carolina universities showed the highest levels of “forever chemicals,” known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances or PFAS, were observed at the Cape Fear region’s main raw water supply at the Kings Bluff pump station on the Cape Fear River.

Supporter Spotlight

The high level was attributed to PFAS chemicals coming from discharges at the Chemours Fayetteville Works plant.

The team of scientists measured a total PFAS level of 425.5 parts per trillion, or ppt, at the station, only two points higher than the nearby Bladen Bluffs station, which only serves the Smithfield Foods plant in Tar Heel, but nearly double the third-highest level found in Harnett County. It is important to note that these numbers only included the study’s first round of testing. A second round is in progress, which identified a preliminary PFAS level of 804.9 at Pittsboro’s water source.

The pumps at Kings Bluff supplies water to at least 350,000 people in New Hanover, Brunswick and Pender counties. The study measured untreated, raw water.

According to the FDA, there are nearly 5,000 types of PFAS, referred to as forever chemicals because of their inability to naturally break down once they are released into the environment. They are man-made chemicals that include PFOA, PFOS and GenX and have been used for U.S. manufacturing since the 1940s.

Currently, only several PFAS chemicals have official health advisory levels and even these are guidelines, not enforceable regulations. Further, while researchers believe PFAS chemicals may impact the human body in similar ways, there’s limited research on what cumulative effects of multiple PFAS might be.

Supporter Spotlight

In other words, it’s not clear if drinking water with 10 ppt each of two separate chemicals is more toxic, less toxic or the same as ingesting water with 20 ppt of a single chemical.

The scientists’ first round of sampling was conducted at 405 sites across the state, according to Duke University chemist Lee Ferguson, who along with Detlef Knappe at North Carolina State University generated the data set.

“This was essentially every municipal water supply as well as some county water supplies across the state,” Ferguson said.

State lawmakers funded the creation of the NC PFAS Testing Network address the presence of the toxic chemicals in the state’s drinking water. The network is a collaboration of scientists from Duke University, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Wilmington, NC State, University of North Carolina Charlotte, East Carolina University and North Carolina A&T university. The group was charged with measuring concentrations of known PFAS compounds and also surveying for a non-targeted analysis of overall PFAS levels at the sites.

The scientists are currently conducting a second round of testing account for variability in PFAS levels that can change due to rain, which causes lower PFAS concentrations due to the dilution of the water, and drought conditions that can cause higher PFAS concentrations, along with other factors. They aim to complete the second round of testing by April 2021, according to Ferguson.

Pender County relies on inconsistent state testing

The first-round data showed Pender County’s raw water supply to be the highest in the state; however, this is simply a matter of the small variability that existed when testing the same water that supplies New Hanover and Brunswick counties on different days.

Ferguson said a total PFAS level of 425.5 ppt is “very high for drinking water,” although he emphasized the water was not yet treated.

“For North Carolina drinking water, raw water samples that we’ve measured, that would definitely be considered high … It certainly gives me pause when it comes to the safety and health of the water for drinking purposes,” Ferguson said.

Although the Pender County Utilities, or PCU, water treatment plant uses a granulated activated carbon filtering system, the same process that CFPUA chose as their preferred option for water filtering, it does not perform its own tests on its treated water. Instead, it relies on the state to test for PFAS levels in its treated water.

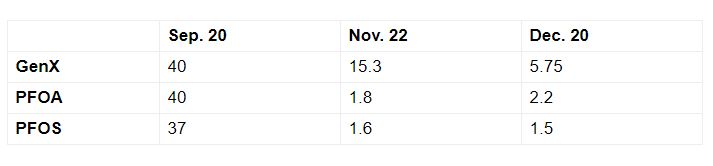

But the state only tests for three known compounds — GenX, PFOA and PFOS — Brunswick County measures 49 compounds and Cape Fear Public Utility Authority, CFPUA, measures 42 compounds. The reason the state tests for PFOA and PFOS is because it has set a combined level health advisory, which is not enforceable in any way, of 70 ppt for those compounds.

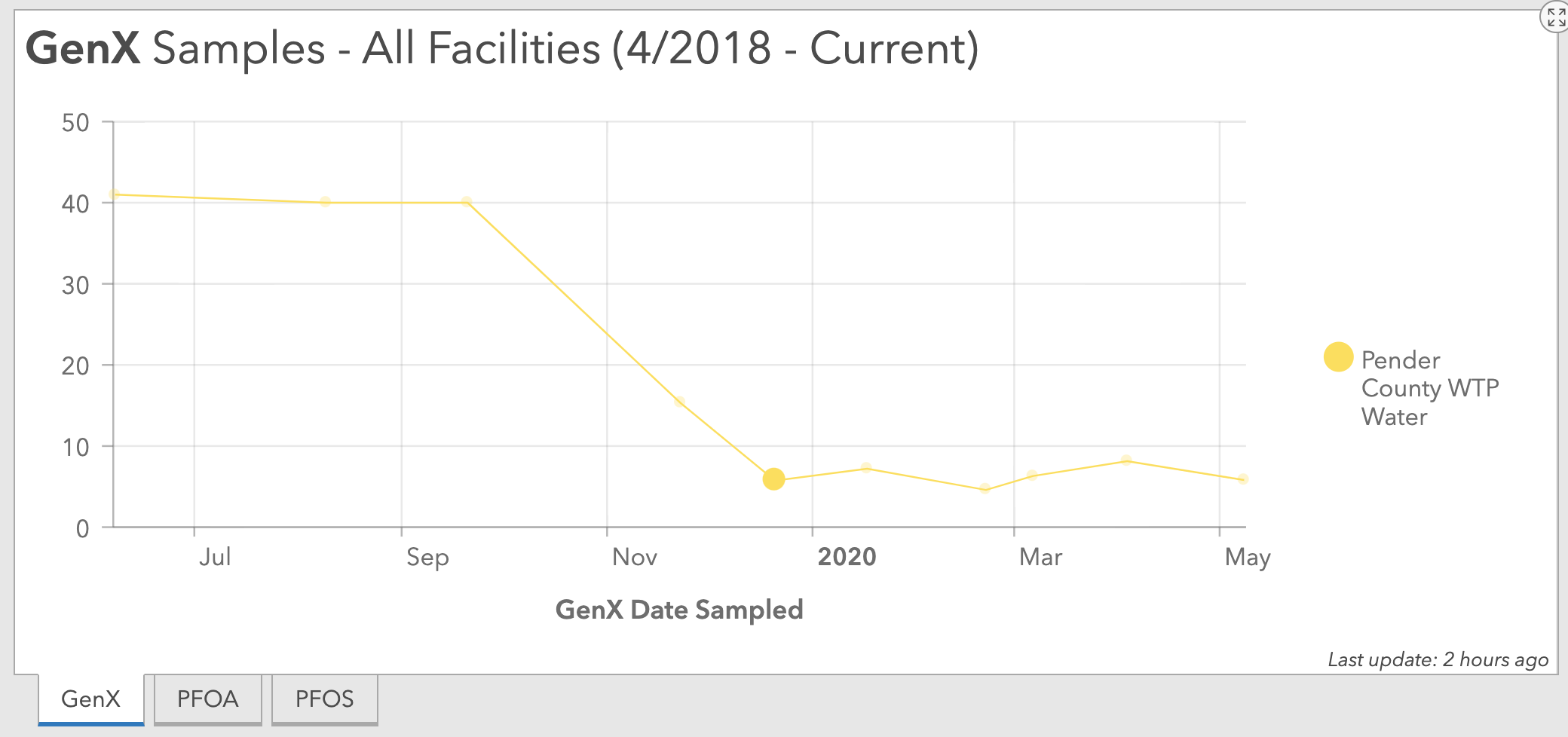

From September to December last year, the state’s Division of Water Resources observed a significant drop-off in GenX, PFOA and PFOS of Pender’s treated water.

Levels of PFAS Chemicals in Pender’s Treated Water, measured in parts per trillion, ppt:

According to PCU Director Kenny Keel, the drop-off was likely due, in part, to a replacement of the filters in October, which is typically done twice a year. But he later added that PFAS levels in the region had also likely dropped.

“It appears that all other systems in the area have seen decreased PFAS levels since November, which leads me to think there has been a decrease in the levels in the river since that time,” Keel said.

Asked if the county was surprised by the preliminary results published by the NC PFAS Testing Network, Pender County spokesperson Tammy Proctor emphasized that the data only showed measurements of raw water on one specific day.

“Even in ‘raw water,’ the sum of PFOS and PFOA is less than 70 PPT as well as GenX,” Proctor said, noting that PCU will “continue to test all water according to state and federal guidelines.”

But before the filters were replaced in October, the combined PFOA-PFOS level was 77 ppt, over the state’s health advisory level. When adding GenX, the level of only three PFAS contaminants in the treated water was 117 ppt.

Because the amount of total PFAS in Pender’s raw water supply has been measured at 425.5 ppt by the university scientists, there is reason to believe the total PFAS level of its treated water in September 2019 was higher than 117 ppt.

“Now, this is a sum total concentration for all the PFAS that we can measure, but still, I consider that to be a risky water (supply) with respect to PFAS exposure, if you think about cumulative exposure,” Ferguson said.

And while Brunswick tests weekly, the state’s testing of Pender’s treated water is inconsistent. For instance, between March and June of last year, 12 tests were conducted. But there were no tests between June 7 and August 9. And over the past fourteen months, the state has only conducted 10 tests of PCU’s treated water, the last in early May.

Furthermore, the county is not publishing those results to its customers, as is done by Brunswick and New Hanover.

“All data will appear in NCDEQ databases,” Proctor said when asked.

‘A large-scale reconnaissance’

As is the case with any water analysis study, the NC PFAS Testing Network method isn’t perfect, mainly because of the large variability it has found in certain areas of the state. Such variabilities can exist from rainfall, drought conditions, sediment being kicked up from the bottom of the rivers during storms, or chemical releases from upriver plants on certain days.

Ferguson acknowledged that time variability is “certainly a big issue particularly in surface water supplies,” as opposed to well water, but the second round of testing is intended to help find more accurate PFAS levels.

But even with a second round now in the works, an average of multiple samples over time would be needed to provide more accurate measurements.

In Pittsboro, for instance, first-round testing on April 9, 2019, showed a total PFAS level of only 54.3 ppt. But testing performed during the second round, which occurred on Septe. 5, showed a total PFAS level of 804.9, nearly double the level recorded for Pender County, the first round’s highest measurement, and nearly 15 times larger than the first measurement taken at the same Pittsboro site five months earlier.

Ultimately, however, the study encompasses such a large area, with 405 water providers, that its main purpose appears to be as a statewide warning indicator versus an in-depth analysis of each site over time, analyses that can be performed frequently by local utility providers, as shown by Brunswick County in its weekly tests.

“Our monitoring study is intended to be a large-scale reconnaissance to identify PFAS problem areas in the state, and we anticipate that utilities that have elevated PFAS in their supplies will conduct more frequent monitoring efforts for these compounds going forward,” Ferguson said.

Frequent monitoring is especially important for a region that draws water downriver from the Chemours Fayetteville Works plant. Last week the plant announced sediment had spilled into the river, causing the state Department of Environmental Quality to investigate the incident. While Brunswick and New Hanover counties conducted tests shortly after the announcement, there is no indication that the state measured Pender’s treated water for GenX or other contaminants in response.

Although Chemours later said the apparent increase in sediment flow into the river was actually the result of natural river conditions, not the company’s construction work, the incident does show the importance of local water providers quickly responding to such incidents.

For Pender County, the question seems to be why they are not performing PFAS measurements itself, which would provide more frequent observations of a larger set of PFAS contaminants. Its plant’s filtration system is more advanced than Brunswick’s, which only uses a traditional filtering system (although it plans to build a $137-million reverse osmosis filtration system by sometime in 2023).

But the higher PFAS levels found last summer, before it replaced its filters and before regional PFAS levels also appear to have dropped, shows that increasing tests would provide a more accurate overview of the plant’s filtration effectiveness at any given time.

This story is provided courtesy of Port City Daily, an online news source for Wilmington and the Cape Fear region, including New Hanover, Brunswick and Pender counties. Coastal Review Online is partnering with Port City Daily to provide readers with more environmental and lifestyle stories of interest about our coast.