This story is the third installment in a continuing series on climate change and the North Carolina coast that is part of the Pulitzer Center’s nationwide Connected Coastlines reporting initiative.

Supporter Spotlight

While hurricanes are woven through the history of Down East Carteret County, a remote string of communities on the central North Carolina coast known for its fishing and boatbuilding traditions, Hurricane Florence was a turning point.

Before Florence hit in September 2018, no one ever talked about sea level rise or climate change, but “Florence is the dividing line. Florence caused everybody to look at things differently,” Karen Willis Amspacher explained in an interview.

Amspacher, who has always called Down East home, is executive director of the Core Sound Waterfowl Museum and Heritage Center on Harkers Island.

“Down East starts at the North River Bridge,” she said. North River Bridge connects Beaufort to the about a dozen communities making up Down East, many of which are bordered by Core Sound.

“I say that North River is not only the geographic divide, but it’s the cultural divide,” she continued, adding there are traits shared with other fishing communities like Hoboken in Pamlico County, Sneads Ferry in Onslow County and Hatteras, Wanchese and Manns Harbor, all in Dare County, but, “Down East, to me, is one of the last vestiges of the values of those old fishing communities that still exist.”

Supporter Spotlight

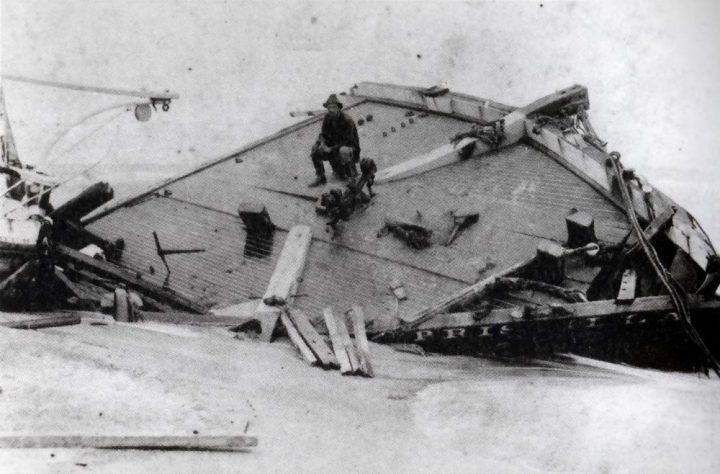

The heritage of many of these communities began more than a century ago on Diamond City, which encompasses all the barrier island communities of Shackleford Banks.

These fishing villages were settled by “hardy families who were accustomed to foul weather and remote lifestyles. But numerous hurricanes and northeasters near the end of the century had tested the endurance of the people known as ‘Ca’e Bankers,’” Jay Barnes wrote in his book, “North Carolina’s Hurricane History.” Excerpts of the book are included in Harm’s Way Digital Archive, Core Sound Waterfowl Museum and Heritage Center’s online exhibit chronicling more than 100 years of storms that devastated the North Carolina coast, including the September hurricane of 1933, or storm of ’33, Hazel in 1954, Dennis and Floyd both in 1999, Isabel in 2003 and Irene in 2011.

“These storms left drifts of barren sand that replaced the rich soils of their gardens, and saltwater overwash killed trees and contaminated drinking wells. These communities had begun to see a decline in population prior to 1899, largely due to the unwelcome effects of hurricanes,” Barnes continued.

The series of storms forced families to move from their barrier island homes, many landing in the Down East communities of Harkers Island and Marshallberg, as well as Salter Path on the Bogue Banks and established the Promise Land community near the downtown area of Morehead City on the Intracoastal Waterway.

Each of the Down East communities has its own personality, its own strengths and its own characteristics, Amspacher continued, “But there’s a common thread among Core Sounders and Down East about place. And I think that’s the tie that binds us to that land.”

Core Sound Waterfowl Museum and Heritage Center works to preserve this heritage of Carteret County, particularly Down East, the family connections and the lives lived in the remote portion of the coast.

The waterfowl museum, which had been closed for 20 months while undergoing an estimated $3.4 million in repairs to damage caused by Hurricane Florence, was to reopen to the public May 22 but due to COVID-19 restrictions, have had to hold off. Initially the museum was set to open April 1 but that was put on hold because of the restrictions put in place to help manage the spread of COVID-19.

A few months before Florence hit, the museum had installed the “Harm’s Way: How Storms Have Shaped Our Communities, Our History and Us,” exhibit and launched the online resource about the more than a century of storms.

The exhibit will be expanded when the museum reopens to include Florence and Dorian that hit in 2019, Amspacher said, and will incorporate key elements of RISING, a North Carolina Sea Grant-funded, photography-oral history project by Ryan Stancil and Baxter Miller that illustrates sea level rise.

The sub-theme for Harm’s Way is response, recovery resilience because “that’s always been the common theme Down East. You take what comes, you did the best can with it, pick it up and move on,” she said. And on the other side of the museum, put in RISING.

“Both of these exhibitions were hanging in the museum when Florence came. Now they are hanging together with a more long-term theme of Living on the Edge and how storms are not the only force changing our landscape,” she said.

With the two exhibits featuring the landscape changing and hurricane history, “We hoped that somewhere in the process with programming and conversation, people would connect the two, and they did,” she said, adding that the exhibits were well-received and came about organically, though, she had to be careful with how it was presented.

Down East folks often see the science community as a threat because a lot of times, fisheries grant research hasn’t always helped them and it has been equated with increased regulation that’s unfair, Amspacher said.

“That being in the mindset, even more so over the past 10 or 15 years with fisheries regulations escalating, fishermen getting more and more involved in the regulatory process, and more and more academics and researchers coming and, some have been positive and some haven’t, they’re skeptical. she said. “The politics around climate change and sea level rise are very real.”

Since Florence, everybody talks about the impacts. “They don’t call it climate change. They’re not talking about the ice caps melting. They’re talking about the next storm,” she said. Florence was a signal more storms are coming and there’s very little question about it, something is changing. “The question is, how am I going to respond to it?”

She said one response was action. Homeowners raised their houses, put on metal roofs and are cutting down pine trees, because they don’t want them on their house.

When asked why folks stay Down East instead of leaving, she responded, “Where in the hell are you going to go? I’m not leaving. it’s home.

“A lot of people left after Isabel and moved to Morehead City. That’s still a move, that’s still changing your life. But people don’t have the money to move, they don’t want to move, they’ve got families here. This is everything they know and anybody who wanted to leave has already left.”

Michele Nolin stayed in her Marshallberg home during Florence.

Initially, she intended to leave when the hurricane strengthened to a Category 5 storm, but she decided at the last minute to stay, Nolin explained in an interview recorded at the waterfowl museum during a community gathering on the one-year anniversary of Florence. The museum has been working with Duke University Marine Lab students to collect oral histories.

Nolin continued that if it had been a Category 1 storm, they’d have just a few fallen limbs to clean up and that would be the end of it, but she was concerned about the storm surge. Her craftsman-style cottage was built in 1920s and is near water on three sides. Because of this, she looked at the tide chart and knew to expect high tide in the early hours.

At about 2:30 a.m., “the winds were howling and limbs were hitting the house. The storm was really rocking at that point,” and she started watching for tide to come. Every 15 minutes she would climb on a stepstool to shine a spotlight out of the three small windows of her front door, the only windows not boarded up, to see if water was rising. The first few times she checked, she saw green grass but around 3:30 a.m., around the time of high tide, she didn’t.

“I saw black and I was looking and shining the light and I could see water lapping,” Nolin said, adding that she wasn’t sure from which direction the water was coming. “I couldn’t really see. But I knew that I had tide in my front yard. I watched it kind of march across my patio and up to the first step of my house.”

Nolin said that the house is single story and there would be nowhere to go if water came inside. She didn’t know how high the water would reach.

“I had no frame of reference for that. I had been told since 1920, including the 1933 storm, there had never been tide inside that house,” she said. “But this is different, everything’s different now. You know, storms are bigger and wetter and they stay a lot longer and they dump a lot of rain and a lot of wind and a lot of surge in the water seems to be higher and higher every year around us.”

She said that this experience taught her how unpredictable storms are and what the unknowns are, “And if you do choose to stay, at some point you are on your own, it’s going to be you and the tides going to do what it’s going to do, and you may not have anywhere to go. And it is has changed me.”

Louie Piner, who is in his mid-70s and a lifelong resident of Davis in Down East, like most of those interviewed for the project, stayed in his home during Hurricane Florence.

He said that the experience with Florence changed how he prepared for Dorian.

“We had no idea that the tide would be what it was in Florence. Nobody expected that,” he said. “Florence was the one of record and that’s the one that my generation will make reference to. My mom’s generation always reference to ’33 storm. My generation will always reference Hurricane Florence.”

Amspacher told Coastal Review Online that 10 years ago, climate change and sea level rise weren’t even on the radar here.

“Isabel (in 2003) came and it tore up Down East more than Florence, I think, in some ways, and nobody equated that with sea level rise, really. It was just a bad storm, like the storm of ’33 or Hazel (in 1954). so there’s 1899, ’33, Hazel, and then Isabel and now Florence,” Amspacher said. “But now, especially with Dorian coming right behind it, I think all the conversation over the past five, six, seven, 10 years, paid off in that when Florence hit, people realized, well, maybe they were right. it had a name. it had a reason.”

Down East communities are particularly vulnerable to the effects of hurricanes, University of North Carolina Marine Institute of Sciences Director Rick Luettich told Coastal Review Online.

Overall, climate change is causing the impacts of hurricanes to be more severe in coastal areas like North Carolina for several reasons, including that a warmer climate is causing the ocean to warm up, making water expand and glaciers melt, both of which are causing sea levels to rise.

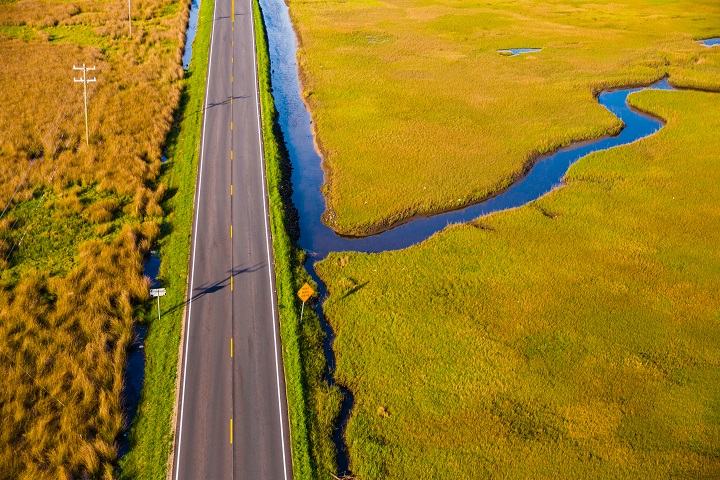

“In areas where the land is already very close to sea level, such as Down East North Carolina, small changes in sea level will cause more flooding on high tides and during storms,” he said.

Another reason is that warm water acts as the energy source for hurricanes. Climate change is likely to cause stronger hurricanes as well as hurricanes that maintain their strength farther north than in the past.

Additionally, climate change causes warmer air temperatures. “A warmer atmosphere is able to hold more moisture. Thus climate change is enhancing the amount of rainfall associated with hurricanes. If a storm moves slowly, such as Florence did in 2018, then greater amounts of rainfall will impact the coastal area,” he said.

“The Down East communities are vulnerable for two basic reasons,” he said. One is that the land is very close to sea level and so it doesn’t take much to make it flood and secondly, due to a variety of physical factors, most hurricanes tend to first move from east to west and then curve to the north.

“While this can and does happen anywhere from the middle of the Atlantic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico, a number of the storms tend to turn to the north, east of Florida, and come up the southeastern U.S. Atlantic coastline. Eastern North Carolina sticks out into the Atlantic Ocean, especially in comparison to Florida and Georgia, and therefore often ‘catches’ these storms coming north. This isn’t particular to climate change, it’s just a fact of our geography and is the reason North Carolina is one of the states that experiences the greatest number of hurricanes,” he said.

Put together the natural tendency for hurricanes to impact eastern North Carolina and the low land there, “With the effects of climate change, one can conclude eastern North Carolina has been getting the short end of the stick when it comes to hurricanes for centuries, and unfortunately climate change is making this worse.”

Hans Paerl, Kenan Professor of Marine and Environmental Sciences at UNC-IMS, said that of all the major storms recorded in eastern North Carolina since 1898, six out of seven of the wettest have occurred in the last 25 years.

Paerl has firsthand experience with flooding caused by Hurricane Florence. He said that he’s been here for 42 years and his Beaufort home, which is close to the North River, experienced flooding for the first time during Hurricane Florence in 2018.

He recently published two papers that “discuss the ‘new abnormal’ of wetter and more frequent tropical cyclones impacting us.”

The Nature Scientific Reports paper shows the increasing trend in wetter storms and is based on a 120-plus year record for the state’s coastal region, he explained. The biogeochemistry paper goes into more detail about the effects of increasing storm activity on water quality and organic matter inputs from coastal watersheds.

He said that the data shows a profound uptick in higher rainfall storms that have impacted the coast over this 25-year timeframe and he doesn’t think there’s any reason to believe that there will be a sudden change in this trend.

“The main cause appears to be due to ocean warming, and that’s not only leading to sea level rise due to more rapidly melting ice caps and glaciers and thermal expansion of seawater, but also at elevated temperatures there’s more water evaporating from the ocean into the atmosphere, generating a ‘rain pump’” he said.

The rise in ocean temperature is driven in large part by man-made emissions of greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide from fossil fuel combustion, methane and oxides of nitrogen from agricultural and industrial activities, and as the ocean’s surface is getting warmer, there is more moisture being generated by evaporation, which is being picked up by storm events and is partly responsible for their higher rainfall content.

“Another factor driving higher rainfall and massive flooding events is that the storms seem to be stalling more along the coastlines due to persistent high air pressure north of us, blocking the storms’ normal tracks to the north and northeast” he said.

Paerl said that the issue of persistent flooding in low-lying areas like Down East is something we’re facing more of and there’s every indication is that it is going to continue for the foreseeable future.

“We shouldn’t let our guard down,” he said, because we are in a region that is very susceptible. “I think we need to be prepared for and accept more flooding associated with these events.”

And if you throw in sea level rise, “It adds a double whammy. As sea level rises, the potential for inundation will be greater.”

Paerl added that “The take home message here is that the recent trends we are experiencing are due to the greenhouse warming effect.”

He said that while we may at times experience very cold winter periods or even an occasional snowstorm, these are short-term, unpredictable or “stochastic” events. “The long-term record is showing us that global warming is occurring at a higher rate than ever and that man-made greenhouse gas emissions play a huge role in this.”

Paerl said the only “knob we can tweak” to slow down this troubling trend is to be committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions.