North Carolina’s first lighthouse, established at Cape Fear on Dec. 23, 1794, was not always easy for mariners to see. The lighthouse has been elusive for historians, as well.

What were the lighthouse’s dimensions? Who was the builder? What was the source of its light?

Supporter Spotlight

Author of the seminal book, “North Carolina Lighthouses,” historian David Stick wrote that records fell short of providing many answers. But the 223-year-old document that lay before me at the National Archives contained many of the answers to Stick’s questions and it guided me toward many more revelations about one of America’s most unique lighthouses.

By the second half of the 18th century, the Cape Fear River had become North Carolina’s principal port of entry. Yet, while a dozen lighthouses were marking entrances to harbors on the American coast, none were in North Carolina. Consequently, the North Carolina General Assembly commissioned its first lighthouse in 1784 to be built under the authority of the Commissioners for the Regulation of Pilotage and Navigation of Cape Fear River.

The conventional style of the day, octagonal lighthouses built of stone or brick tapering from the ground like a pyramid, was based on the architectural design of New York harbor’s first lighthouse established in 1764 at Sandy Hook, New Jersey.

Design specifications for Sandy Hook were shared with other Colonial governments, including Delaware, which used the plans to build Cape Henlopen Lighthouse. As I read the document at the National Archives, however, I discovered that the 1794 Cape Fear Lighthouse was not built according to the Sandy Hook prototype but featured a distinctive design shared exclusively by only one other American sentinel.

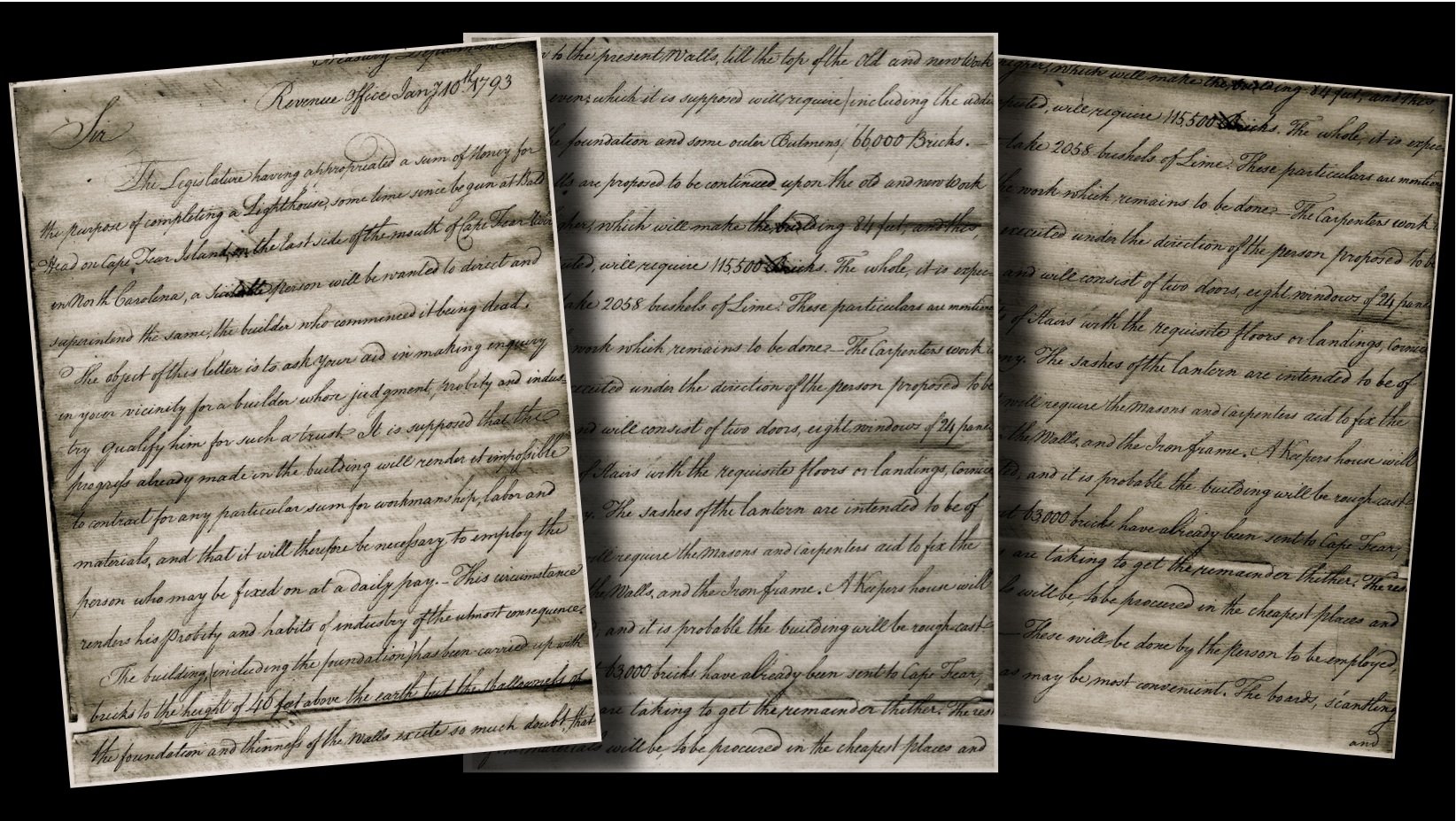

The document was a handwritten advertisement sent in January 1793 to several customs collectors, mostly in Northeast states, seeking a qualified building superintendent to complete the unfinished lighthouse on “Cape Fear Island.”

Supporter Spotlight

Construction of the tower had begun a few years earlier. When the structure had reached an elevation of 46 feet, the unidentified builder died. By then, the responsibility for construction and management of the fledgling nation’s lighthouses had been transferred from the states to the Federal Treasury Department and its Commissioner of Revenue Tench Coxe.

Coxe’s five-page job posting was quite detailed regarding the Cape Fear Lighthouse’s design specifications and the necessary requirements for completing the tower and lantern, including a description of the work that had already been done:

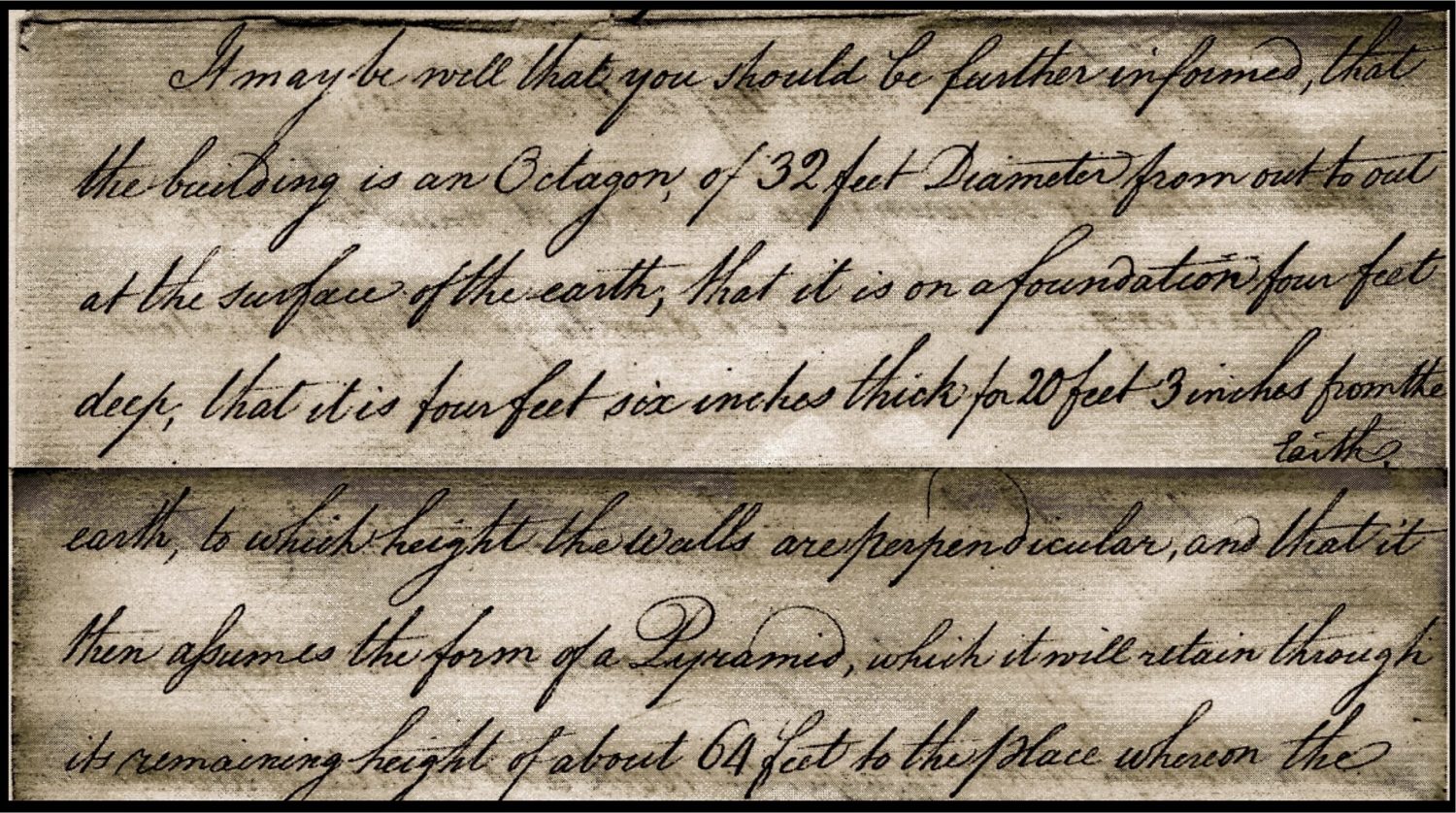

“It may be well that you should be further informed that the building is an octagon of 32 feet diameter … that it is on a foundation four feet deep, that it is four feet six inches thick for 20 feet 3 inches from the earth, to which height the walls are perpendicular, and that it then assumes the form of a Pyramid, which it will retain through its remaining height of about 64 feet to the place whereon the lantern will be laid.”

A cursory reading of the document might overlook the remarkable statement that the lowest 20-foot-high section of the Cape Fear Lighthouse was “perpendicular,” or vertical, above which the tower’s pyramidal shape commenced. The uncommon form — a box-like base, or first story of 20 vertical feet — was shared by only one other octagonal American lighthouse at that time, the 1768 Charleston Lighthouse that was depicted in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper in April 1861, a few months before it was destroyed by Confederate saboteurs.

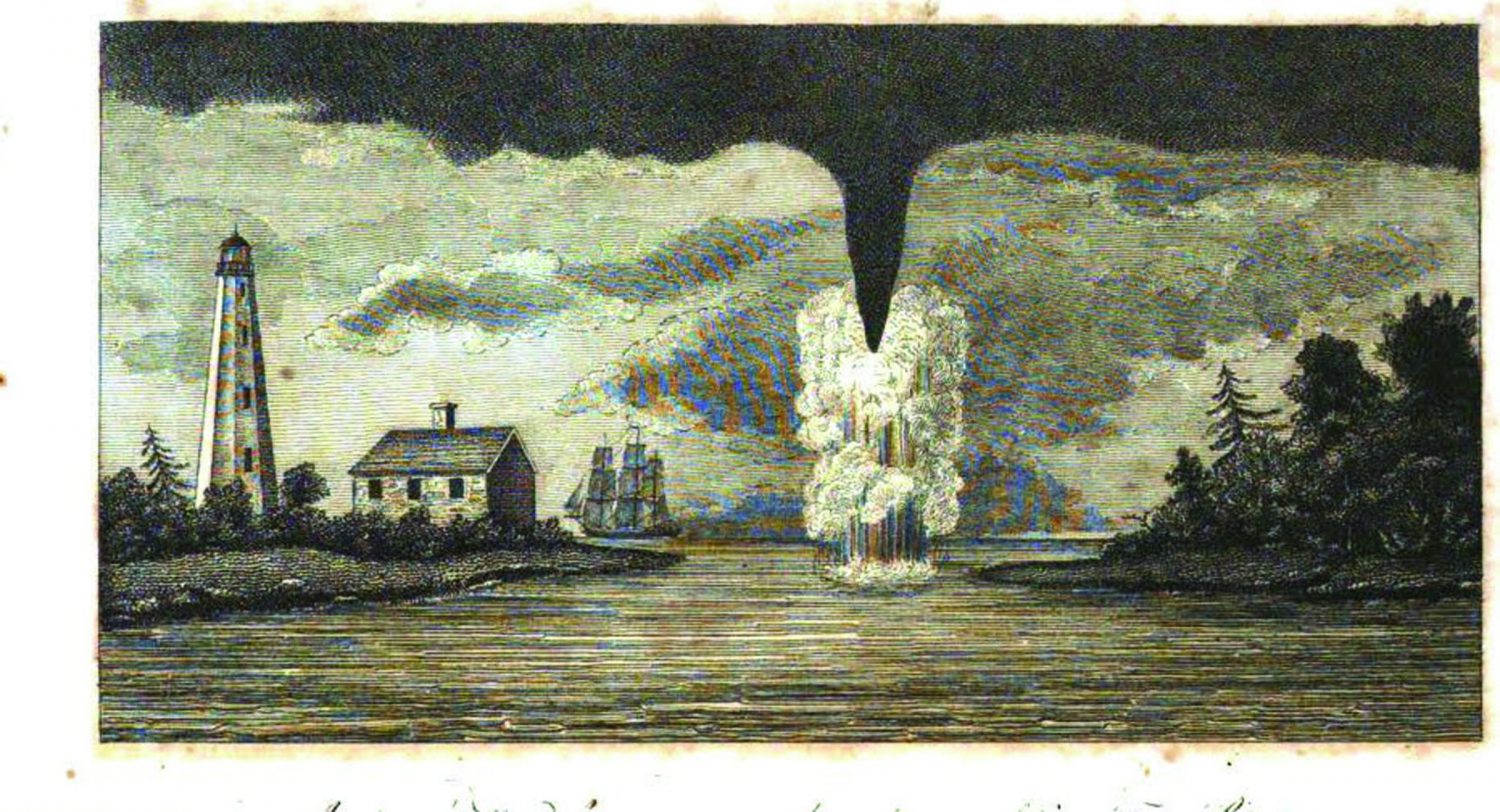

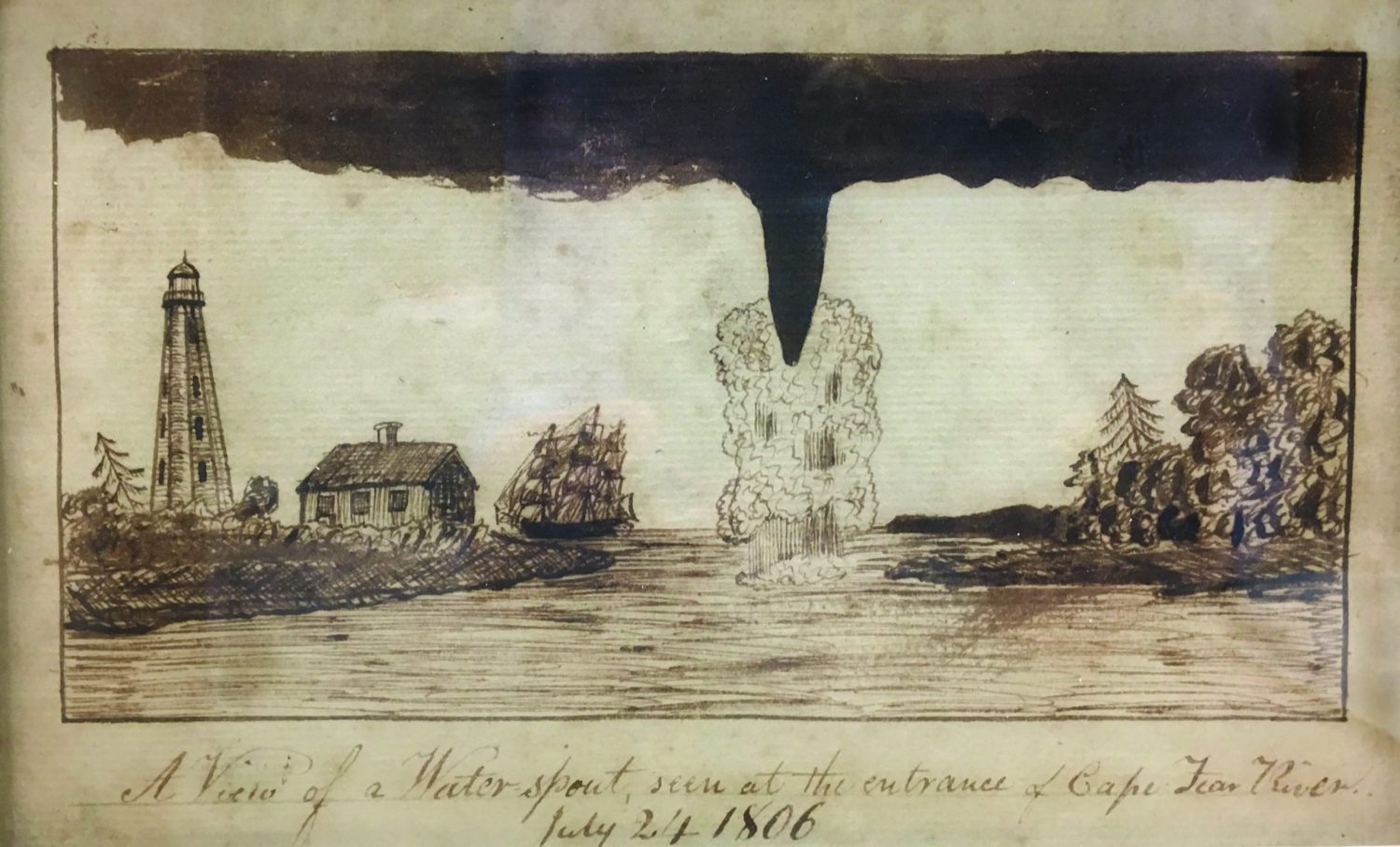

For many years, historians believed that there was only one extant illustration of the state’s first lighthouse at Cape Fear, a woodcut derived from an original hand-drawn sketch, titled “A View of a Waterspout Seen at the Entrance of Cape Fear River July 24, 1806.” The woodcut was published in January 1812 in an early American weekly magazine titled, The Port Folio. Dominating the center of the sketch, beneath a darkly ominous sky, is a waterspout churning the waters of the river. A ship in full sail heading south appears to be escaping the watery vortex.

And on the left side of the illustration is North Carolina’s first lighthouse adjacent to a two-story keeper’s house. Detailed as it was, the drawing was unintentionally deceiving. From their precarious vantage point in the middle of the river with a waterspout bearing down on them, the artist could not see what lay behind the cedar trees and wax myrtle bushes that were hiding the unique first story of the lighthouse.

The artist’s original sketch has survived and is owned by Old Baldy Foundation.

There is a conspicuous difference between the original drawing and its published reproduction. The sculptor of the woodcut chose to include only four windows on a single side of the lighthouse when, in fact, there were four windows on four faces of the eight-sided building. According to Coxe’s advertisement, “eight windows of 24 panes” were still required to be framed by a carpenter after the eight lower windows on four sides of the unfinished 46-feet of tower were already installed.

This proved to be an important clue for my research into the architectural design and pedigree of the Cape Fear Lighthouse.

Most significantly, the window configuration on the original hand-drawn sketch of Cape Fear Lighthouse is identical to the windows appearing on the Charleston Lighthouse published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, hinting that it too must have had a total of 16 windows. Moreover, no octagonal lighthouse built during either the American colonial period (1716-1791) or the early Federal period (1792-1817) is known to have been built with columns of windows on four faces of the tower except for the Cape Fear Lighthouse and the Charleston Lighthouse depicted in 1861.

The architecturally proportional windows of the two towers were more aesthetic than utilitarian, more typical of a church steeple than a lighthouse.

Additional evidence supporting the uncharacteristic design of the Cape Fear Lighthouse and its similarity to Charleston’s lighthouse depicted in 1861 can be found on a map created in the late-1790s by surveyors Jonathan Price and John Strother titled, “A Map of Cape Fear and its Vicinity from the Frying Pan Shoals to Wilmington.” Praised for its high degree of accuracy, the map depicts the Cape Fear Lighthouse located on the extreme west point of Bald Head Island and standing atop its box-like first story.

All three items of evidence, the original “Waterspout” drawing, the Revenue Commissioner’s 1793 description, and the 1798 Price/Strother map, provide sufficient evidence to conclude that the Cape Fear Lighthouse completed in 1794, and the Charleston Lighthouse illustrated in 1861 were similar, if not identical in their designs. Further, the two structures, neighbors 116 nautical miles apart, were unlike any other American lighthouse of their time. This analysis leads to an obvious question: Were the two lighthouses designed by the same architect?

Perhaps they were not just neighbors, but sisters.

The Charleston Lighthouse, completed in 1768 was the South’s first lighthouse and, at 96 feet to the roof of the dome, America’s tallest tower at the time it was built. When the Cape Fear Lighthouse was topped with its 15-foot iron lantern and dome, it became the nation’s tallest.

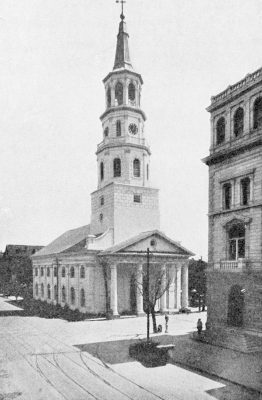

Samuel Cardy, a builder from Dublin, Ireland, was the lighthouse’s architect and construction superintendent. Cardy was highly regarded for having built Charleston’s St. Michael’s Church, the plans of which were based on St. Martin-in-the-Fields Church in London.

The crowning glory of St. Michael’s Church, and Charleston too, is the church’s magnificent 185-foot-tall steeple, an octagonal tower built atop a massive square platform. As one gazes at the imposing steeple of St. Michael’s Church, it becomes apparent that Cardy naturally would have turned to the familiar architectural form for the Charleston Lighthouse, a design that stood apart from all other American lighthouses. It also seems logical that the Cape Fear River Commissioners would have sought the skills, experience and design plans of the builders of neighboring Charleston’s lighthouse.

Even though the identity of the initial builder of the Cape Fear Lighthouse remains a mystery, it is difficult to imagine that the first 46 feet of the sentinel, with its unusual square first story, would have been built by someone without firsthand knowledge of Samuel Cardy’s distinctive Charleston tower based on a famous church steeple. Nevertheless, North Carolina’s first lighthouse was doomed even before its construction began.

Perhaps for cost savings, the lighthouse was not built atop a stone foundation like its older sibling at Charleston. Instead, its square first story of 4 1/2-foot thick walls rested upon a shallow brick foundation 4 feet below grade. In comparison, the first Cape Hatteras Lighthouse’s granite foundation in 1798 was laid 13 feet below grade.

This unconventional footing worried the Commissioner of Revenue in Philadelphia who wrote, “The firmness of the ground on which the building stands does not appear to be sufficiently ascertained,” and “the shallowness of the foundation and thinness of the walls excites much doubt” about the tower’s stability. But despite these concerns—and the opinions of some historians—the lighthouse’s defects did not cause its demise. In fact, it stood and functioned quite proudly for 21 years.

Many writers have claimed that the lighthouse was built too close to the banks of the Cape Fear River, which ultimately undermined the tower. This is not true — Wilmington’s commissioners and the lighthouse’s builders would not have made such a careless error. Instead, it was a mostly imperceptible process that had been taking place over 30 years that eventually endangered the structure.

The opening of New Inlet to the north of Cape Fear, which was caused by a hurricane in 1761, had produced a dramatic and inexorable change to the hydrology of the mouth of the Cape Fear River. Erosion accelerated and began to rapidly wear away the shoreline in the direction of the Cape Fear Lighthouse’s shallow foundation. By the summer of 1813, the collector of customs at Wilmington reluctantly ordered the lighthouse dismantled so that its iron and glass “bird-cage” lantern and tower bricks — not just a few but as many as 600,000 bricks — could be recycled to build a new lighthouse in a more stable location.

That tower, completed four years later about a mile to the northeast, is the present day Bald Head Lighthouse.