MOREHEAD CITY — Disinfecting your home is a critical part of slowing the spread of COVID-19 and a University of North Carolina Institute of Marine Sciences professor has created an infographic to help get the word out.

Rachel Noble, a professor of public health microbiology, told Coastal Review Online Monday that the infographic is intended to make accessible to the community accurate information about disinfecting the home and what can be used that’s already around the house.

Supporter Spotlight

“We know that because the virus can live on both porous and nonporous surfaces for a period of time,” she said, adding it looks like that it could be from about two to nine days, depending on the type of surface.

“This particular virus is fairly sinister in the fact that it only takes a few particles to make you ill,” she said, and these very small viruses can be carried. Being diligent about disinfecting and taking precautions is helping flatten the curve, or keeping the daily COVID-19 case load manageable for medical providers.

She said the goal with creating the infographic is to simplify the information found on federal agency websites and make it available in one spot, increasing the likelihood of the public finding the information.

“So, there’s a lot of information out there. Most of it is accurate and will help someone disinfect the home and we just hope to provide it in a simple format so that people could access it,” she said.

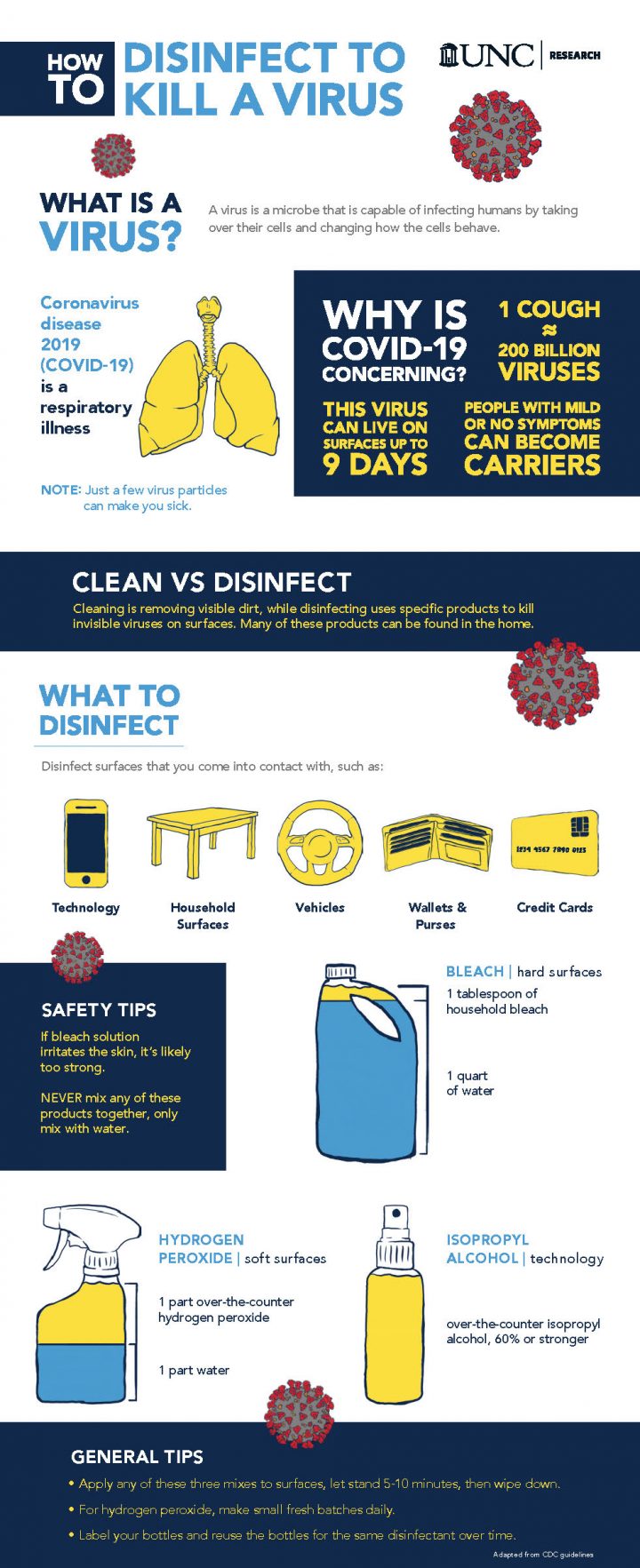

Noble compiled the information featured on the graphic created by UNC Research on how and what to disinfect. The infographic suggests a solution of 1 tablespoon of household bleach to 1 quart of water for hard surfaces; 1 part over-the-counter 60% or stronger isopropyl alcohol to 1 part water for technology; and 1 part over-the-counter hydrogen peroxide to 1 part water for soft surfaces like a wallet or purse. Apply, let stand 5-10 minutes, then wipe down.

Supporter Spotlight

“The point is that disinfecting and the ways that you think about disinfecting have to be different from just cleaning the home,” she said.

Without disinfecting, a person can touch a contaminated surface and transfer any number of those virus particles onto their hand and then to their face.

Noble said that most households across the country are doing a good job to prevent the spread, like social distancing, but one of the risks that remains are having to leave home for necessities such as for groceries, the pharmacy, bank and gas station.

“Those are realities. People are going to do it once a week or once every two weeks. Some people might be in a position, income wise, that they need to do it every three or four days. Those things are all going vary and we see people doing the best that they can,” she said.

The frequency and purpose of trips from home determines how often a person should disinfect their home. For example, if a person works an essential job, they’ll need to disinfect more.

“The disinfection process scales up and scales down, according to how much people are exposed to outside potential sources of this particular coronavirus,” she said.

Noble explained that upon returning home, the best process to disinfect is in the exact reverse of how you went out.

After pumping gas and properly disposing of gloves, you’ll touch the door handle, then steering wheel, and maybe the radio or your phone. “You have to work your way backwards and re-disinfect all of those surfaces that you touched.”

It’s an important part of being preemptive, she reiterated, but isn’t meant to be fearful; just work backward in a systematic way. Once this has become habit, you’ll be prepared if your particular area sees a surge in case counts and will help reduce the number of total people overall that are hospitalized.

Noble said that people need to assume that any time they’re in a public space and have contact with others, they should treat the situation as a potentially contagious event and be proactive about disinfecting.

For every patient with a positive, lab-confirmed COVID-19 test, she said that she calculates a ratio of five or 10 people that are infected but aren’t tested. Noble said that it’s a hard number to gauge and really depends on location; some states are doing a better job of testing the population than others.

She used Carteret County as an example. If there’s 15 confirmed cases here, she said that it’s most likely somewhere around 150 cases, though it could be much more — around 200 or 300 cases — or it might be fewer. “But that’s the way I think about it from everything that I’ve read, save for the places who have done a really good job of testing, where their numbers are higher.”

For those communities with higher numbers, it’s most likely because there’s more testing and not a failure of the residents to comply with social distancing measures. Washington and New York have been proactive because of the population density.

In Eastern North Carolina, the population is spread out with small pockets. A person who doesn’t know they’re infected in a small community would transmit the virus to significantly fewer people than in bigger city.

Noble said she was trying to read more about rural disease transmission but found there was no information; that all the models were based on major metropolitan areas. She’s putting a proposal together to look into rural disease transmission.

Regarding masks, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now recommends wearing cloth face coverings in situations that are difficult to maintain social distance.

Noble said that the masks are a key, but a lot of people are forgetting the details.

“First, the nose piece is crucial, without it, the air goes in the top of the mask and settles on or in the nose,” she said. “Second, boil or wash the masks after each use.”

She recommends making a mask for every other day of the week. Wash as soon as you return to home in hot water or boil in water for 5 minutes and then hang to dry in a safe private place — in sun would be excellent — and then only use that mask at least five days from that time.

She said that UV light, which is effective at breaking down coronaviruses, can complement other disinfecting steps, although natural sunlight doesn’t have the same properties as radiation in a clinical hospital setting and shouldn’t be relied on to disinfect.

“It’s one of those things that like helps, but it’s not a magical zap,” Noble explained.

After washing a cloth mask properly using detergent, hot water and bleach additive, set it in the sun as a great additive step.

“Finally, the air has to come through the mask, not around the mask, so if you use too many layers of cloth you are actually defeating the purpose. The cloth has to be very tightly woven, think high thread-count bed sheet, not the material of a sweater or any loose knit,” she said.

“One of the biggest pieces of advice is to really cut down on social interaction. Continue to be vigilant,” Noble said. It’s important to people in your community of all shapes and sizes, not just the older people but it might be that the child down the street who was just diagnosed with type 1 diabetes or you might be protecting a friend who in the medical field.

Rick Luettich, director of the UNC IMS, told Coastal Review Online that the mission of the institute is to provide service to the state through research, education and engagement.

“We are extremely fortunate to have Dr. Noble, a nationally renowned expert on viruses, on our faculty and we are pleased that she is able to share her expertise with our community. All of us at Carolina’s marine lab live and work in eastern North Carolina; we want to do everything we can to help our community during this extraordinary time,” he said.