The sudden appearance of a bottlenose dolphin mounding its back and flashing its dorsal fin at the surface is always an unexpected thrill. And when one is seen, more are almost certain to follow.

Some may emerge in unison within inches of each other, while others may be scattered hundreds of yards apart yet clearly moving as a group. Who can resist stopping whatever their doing to watch where they’ll come up next?

Supporter Spotlight

Bottlenose dolphins, or Tursiops truncates, are hardly unique to North Carolina. They occur in tropical and temperate coastal waters around the world. Their common occurrence close to shore probably makes them the most frequently sighted of all the world’s more than 80 species of whales and dolphins. Their widespread distribution, however, hasn’t prevented local interests from proclaiming special recognition to the dolphins in their area. This is a good thing, however. It can help encourage local research and protection measures which are vital for conservation.

In North Carolina, for example, House Bill 598 filed in April 2019 would designate bottlenose dolphins as the state’s official marine mammal. Introduced by Reps. Bobby Hanig, R-Currituck, and Holly Grange, R-New Hanover, the bill won unanimous approval in the House and passed a first reading in the Senate, where it was then referred to committee. The North Carolina General Assembly is set to convene April 28, but some legislative committee meetings scheduled for this week have been canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite widespread distribution, bottlenose dolphins are divided into hundreds of discrete local and regional populations, or stocks, worldwide. Although the range of each stock typically overlaps at least one neighboring stock, each is biologically isolated to varying degrees by subtle social, ecological and behavioral differences. These differences reflect generations of experience learning about how to exploit the specific conditions in a given area. Consequently, stocks can differ widely in abundance, geographic range, food preferences, migratory patterns and other characteristics. But the loss of any one stock can leave a long-term gap in a species’ range and decrease its overall genetic and behavioral diversity.

Subdivided stocks

The National Marine Fisheries Service, or NMFS, the federal agency responsible for conserving most marine mammals in U.S. waters, recognizes 16 overlapping stocks of bottlenose dolphins between New York and southern Florida (S.A. Hayes et al 2019). Six, the oceanic stocks, occur primarily or exclusively in ocean waters, while 10 others are confined largely to specific inshore bays, sounds, and estuaries – the estuarine stocks.

The current subdivision of stocks is by no means a settled matter. Researchers at the NMFS Southeast Fisheries Science Center are developing techniques to identify genetic differences between the various U.S. bottlenose dolphin stocks and their work to date is promising. If successful, minute skin samples may soon be sufficient to identify which stocks individual animals belong to. This could result in some significant changes in the number or range of recognized stocks recognized along the Atlantic Coast.

Supporter Spotlight

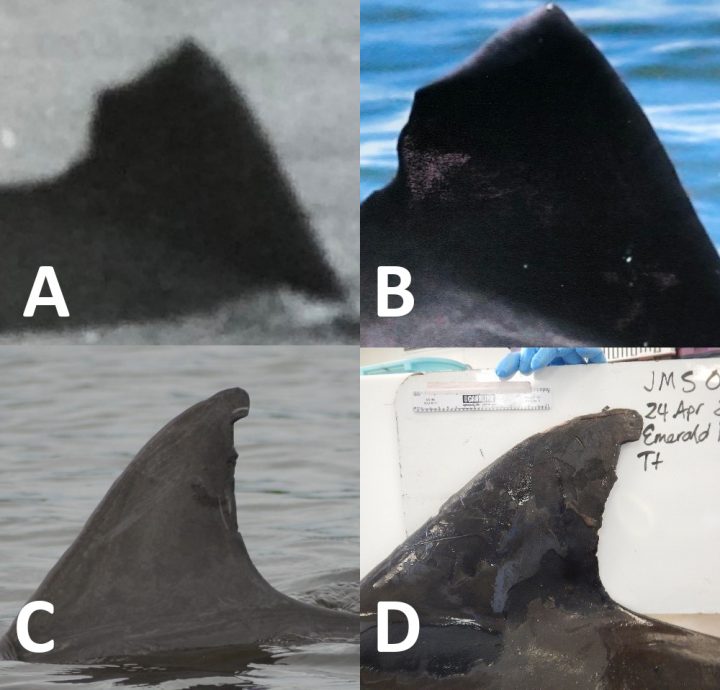

As recently as the 1980s, East Coast dolphins were thought to be divided into just two stocks, an inshore and offshore stock. The more complex recognition of 16 stocks came to light as a result of recent studies using satellite telemetry tags and photo identification to track the movements of individual animals. And if current stock delineations further change significantly, it could lead to profound changes in conservation needs.

In North Carolina, photo-ID techniques were first applied to dolphins by Natural History Curator Keith Rittmaster at the North Carolina Maritime Museum and N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries Marine Mammal Stranding Coordinator Dr. Victoria Thayer, near Beaufort in 1985. Similar efforts around the state followed a decade later with Rich Mallon-Day working at the Nags Head Dolphin Watch on the Outer Banks, Dr. Laela Sayigh at the University North Carolina Wilmington and Dr. Andy Read at Duke University Marine Laboratory.

By the mid-1990s, scientists working to photo-identify bottlenose dolphins along the East Coast realized that, by pooling their local photo catalogues, a far more complete picture of dolphin movements and biology could be gained. Thus, in 1997, Kim Urian, a research analyst at Duke Marine Lab in Beaufort, cooperated with researchers and research organizations all along the East Coast to compiling single catalogue for all photo-identified dolphins along the Atlantic Coast

Initially funded by NMFS and still maintained by Urian, the result, the “Mid-Atlantic States Bottlenose Dolphin Photo-Identification Catalogue,” includes contributions from 37 researchers and research groups. It contains more than 24,000 photographs of 15,400 individuals from the New York Bight to the Indian River in Florida. It includes 8,403 photographs of 5,424 individuals from North Carolina alone. Because most dolphins lack distinguishing marks or go unphotographed, and some identified dolphins have since died, the numbers represent an unknown portion of the total. And most are not assigned definitively to specific stocks, given limited sighting histories.

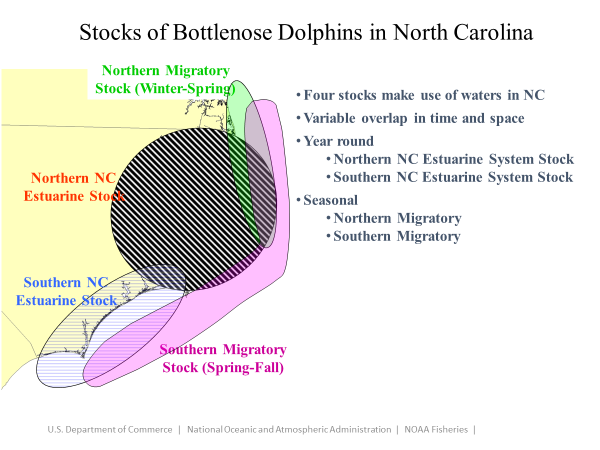

Based largely on these studies, five of the 16 East Coast stocks are found at least seasonally in North Carolina. Of the five stocks in North Carolina, two are estuarine and three are oceanic stocks. With the migratory patterns of each overlapping one or more adjacent stocks at different times of the year, North Carolina is one of the hardest areas on the East Coast to assign sightings or dead stranded dolphins to a particular stock.

One of the two estuarine stocks, the northern North Carolina estuarine stock is centered in northern parts of the state in Albemarle, Pamlico and Core sounds. Some of its members, however, have been seen as far north as the lower Chesapeake Bay, Virginia, in summer, and south to Wilmington or beyond in fall and winter. It currently numbers an estimated 782 dolphins.

The southern North Carolina estuarine stock is smaller. It occurs primarily in bays and sounds between the New River near Jacksonville and the South Carolina border, but some members have been photographed as far north as Core Sound near Beaufort in summer. There is no recent estimate of abundance for this stock, but photo-identification studies completed more than 15 years ago suggested it numbered fewer than 200 dolphins at that time. Individuals in both the northern and southern estuarine stocks occasionally pass through inlets traveling and foraging close to shore – generally within a few hundred yards of the beach.

The abundance and range of oceanic stocks tends to be greater than estuarine stocks, which is certainly true for the three stocks occurring at least seasonally off North Carolina. One – the offshore stock – ranges over the outer half of the continental shelf from Florida to southern New England and is by far the largest on the East Coast. It numbers some 75,000 dolphins. Although occupying federal waters well beyond the state’s 3-mile jurisdiction, dead individuals from this stock sometimes wash ashore in North Carolina. Offshore dolphins tend to be larger and more robust than animals closer to shore and may even represent a separate species of dolphin.

The two other oceanic stocks off North Carolina are coastal stocks living over inner portions of the continental shelf generally between 3 and 40 miles of shore. Frequently, however, some of their members move to within a mile or less of the beach and will even poke into the mouths of inlets. Both coastal stocks migrate north in spring and south in the fall, but with different ranges they tend to occur off North Carolina at alternating times of the year.

The northern coastal migratory stock ranges from North Carolina in winter to New York in summer and is estimated to number more than 6,000 animals. The Southern Coastal Migratory Stock moves from northern Florida in winter to Virginia in summer and is thought to number about 3,700 animals. Thus, whereas the northern coastal stock is generally present off North Carolina in winter, the southern stock is present in summer. Both stocks, however, may be present off North Carolina in late fall and early winter.

Conservation issues

The bottlenose dolphin stocks in North Carolina currently appear to be stable and healthy. Dolphins, however, are subject to human impacts. They can be injured or killed by entanglement in fishing gear and collisions with boats, and both pollution and disruption of natural behaviors can affect their health and reproduction, cause stress, and shorten their life spans. Such impacts can precipitate declines and even their disappearance in local areas. This is particularly true for small stocks, such as those in the state’s estuaries where exposure to human impacts is greatest. Assuring the stability and health of dolphin stocks in North Carolina therefore requires ongoing studies to monitor human-related injuries and deaths, track the abundance and reproduction rates of each stock, and assess the health of dolphins within stocks.

In this context, House Bill 598 is an important and worthy step. Although it authorizes no new funding or mandates for research or management, its formal recognition of bottlenose dolphins as a significant part of the state’s coastal ecosystem would increase public and scientific attention, and could encourage state, federal and non-governmental agencies and groups to use their own resources and abilities to help meet needs related to local bottlenose dolphin research and conservation.

With public support for House Bill 598 over the coming months in the form of letters to elected state representatives, it’s possible that bottlenose dolphins could be the official North Carolina marine mammal before the end of the year.