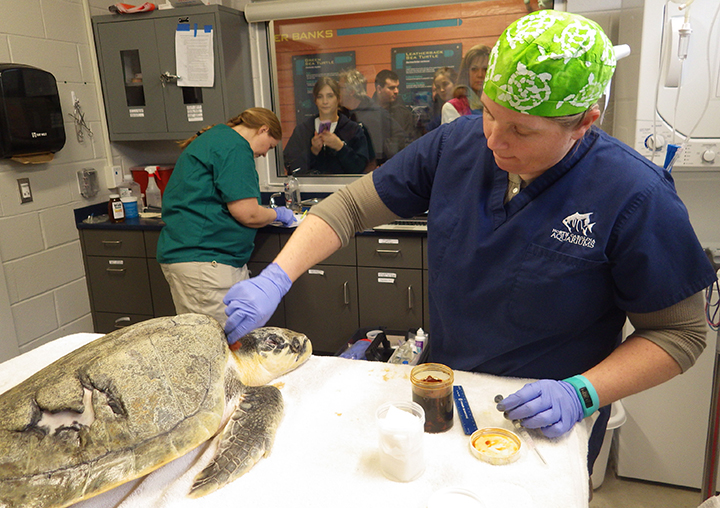

In her workweek, Dr. Emily Christiansen might remove a tumor from a fish, perform an annual health exam on a moray eel, care for a sea turtle’s wound, treat a river otter’s injured paw and help researchers study sand tiger sharks off the North Carolina coast.

As a veterinarian for the North Carolina Aquariums, Christiansen spends about nine intense days per month checking and treating animals at the three aquariums on the state’s coast. She spends the rest of her workweek updating animal records, preparing for upcoming aquarium visits and responding to a slew of calls, texts and emails from aquarium staff, veterinary residents, researchers and concerned citizens.

Supporter Spotlight

Growing up in the suburbs of Philadelphia, she didn’t have her heart set on becoming an aquatic animal veterinarian from a young age. She did go through a phase of wanting to be a dolphin veterinarian but outgrew it.

In college, Christiansen almost majored in linguistics because of her fascination with language. She chose biology though, since it would satisfy course requirements in case she decided on a career in animal medicine, toward which she was starting to gravitate.

After graduating, she moved to Florida to intern at the Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium while applying to veterinary school. With her acceptance to Tufts University School of Veterinary Medicine, her colleagues nudged her onward.

“They kicked me out because I got into vet school. Otherwise I’d still be there, scooping turtle poop,” she laughed.

Christiansen knew she didn’t want to work with dogs or small animals, which is why Tufts’ wildlife medicine program attracted her. She earned both a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree and a Master of Public Health.

Supporter Spotlight

As a new doctor, she interned at a bird rehabilitation center in Florida, then went back to Tufts to intern in wildlife medicine and teach vet students, all while applying to residency programs. Though internships and residencies aren’t required to practice animal medicine, they’re needed for specialty certifications, Christiansen explained.

In 2011, Christiansen moved to North Carolina to start a residency program at N.C. State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine. It’s one of fewer than 20 schools in the country to offer training programs in zoological medicine, a specialty that includes wildlife, zoo animals and aquatic animals.

Christiansen spent most of her three-year residency focusing on aquatic animals at the coast, where the N.C. State Center for Marine Sciences and Technology, or CMAST, offers clinical training with nearby aquariums, sea turtle hospitals, marine mammal and turtle stranding networks. Dr. Craig Harms, director of the Aquatic Animal Health group at CMAST in Morehead City runs the residency program.

The program is fast-paced. Students must publish five research studies and prepare for a grueling two-day specialty board exam, where they’re expected to know all the latest research published in dozens of journals on zoological medicine.

After finishing, Christiansen never left the coast. Just 15 days after her residency ended, she became the N.C. Aquariums’ first full-time veterinarian. The North Carolina Aquariums initiated the position to improve animal care and comply with recommendations from the Association of Zoos and Aquariums as an upgrade from their once-a-month visits from Harms.

Christiansen kept her ties to N.C. State. She’s an adjunct faculty member and her office is based at CMAST. She helps coordinate with N.C. State zoological medicine residents in her work at the aquariums.

The three state aquariums are located at Roanoke Island on the Outer Banks, Pine Knoll Shores on Bogue Banks, and Fort Fisher just south of Wilmington. While the aquarium at Pine Knoll Shores is just a 20-minute drive from CMAST, it’s more than three hours to Roanoke Island and two and a half hours to Fort Fisher. Visits to the more distant aquariums make for long days for Christiansen and veterinary technician Heather Broadhurst, who check and treat about 30 animals per visit.

Animals can’t always wait for a scheduled vet visit, though. When asked if she was always on call, Christiansen pulled two smartphones out of her pockets. In many cases, she can guide aquarium staff through procedures over the phone. Staff are uniquely skilled to handle ailing animals, she noted, especially at the N.C. Aquarium on Roanoke Island, which is home to the Sea Turtle Assistance and Rehabilitation, or STAR, Center. Christiansen typically needs to visit the aquariums for emergency visits “only a handful of times a year,” she said.

Caring for such a wide variety of aquarium animals, from river otters to bald eagles to stingrays, seems daunting, but Christiansen responded that “they’re all animals,” meaning they have the same basic internal systems.

Her work not only benefits the aquarium animals and their 1.3 million annual visitors but also helps researchers investigate how to conserve aquatic species.

Animal cases can be used as research opportunities for veterinary residents at N.C. State and other local collaborators. Many cases the aquarium team sees aren’t in the books yet, Christiansen explained, and the aquatic animal medicine field is still relatively new. For unfamiliar cases, she’ll often need to try out a treatment and see if it works. She also consults other aquariums across the country to see what they’ve already tried for similar cases.

Wildlife researchers also seek Christiansen’s help.

“I get tapped for a lot of cool projects that need a vet or need to train graduate students,” she mentioned.

For example, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration researchers from the Beaufort Lab may need her on board while they study sea turtles. She may need to teach area graduate students, such as those from CMAST or the University of North Carolina Institute of Marine Sciences, also in Morehead City, how to surgically implant a small tracking device in a fish.

She’s also involved in fieldwork for a collaborative project on sand tiger sharks. The species is in decline and doesn’t reproduce in captivity, Christiansen said. Pregnant females hang out off the North Carolina coast around shipwrecks, and researchers are tracking them to determine where they travel and give birth. The project was started by Madeline Marens, a master’s student at UNC Wilmington and an aquarist at the N.C. Aquarium at Fort Fisher.

The N.C. Aquariums are involved in other conservation research projects as well, and spearheaded the Spot A Shark citizen science project for divers to submit photos of sharks.

Despite these efforts, the N.C. Aquariums are not always seen as a major research institution in eastern North Carolina, even though they were originally founded as the N.C. Marine Resources Centers in the 1970s and displayed researchers’ work. Christiansen is on a mission to change that. As someone straddling both worlds of aquariums and academia, she fosters collaborations between researchers, veterinary trainees and the aquariums to create win-win scenarios.

Though not in her job description, Christiansen is also seen as the friendly neighborhood wildlife expert in Beaufort, where she’s resided for the past eight years. Inquisitive children she coaches in youth soccer will come to her with turtles and other animals they find.

She also inspires students at outreach events, such as the annual Girls Exploring Science and Technology, or GEST, event for middle schoolers at the Duke University Marine Lab in Beaufort and the Women in Science Day at the N.C. Aquarium at Fort Fisher. At GEST, she spends a Saturday teaching students how to anesthetize a fish and then take measurements like weight and heart rate. She’s also participated in a GEST panel discussion, sharing her own journey to becoming a veterinarian.

Christiansen said she plans to continue developing partnerships between the research community and the aquariums, and her work as a veterinarian and community member help drive the N.C. Aquariums’ mission of “inspiring appreciation and conservation of North Carolina’s aquatic environments.”