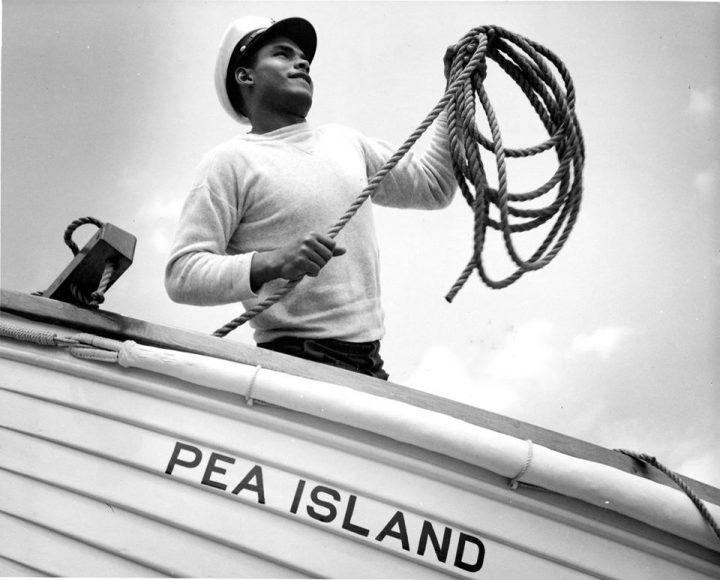

MANTEO — Around the time of a near-miraculous rescue of shipwrecked passengers off the Outer Banks by the all-black crew at the Pea Island Life-Saving Station, other blacks living more than 200 miles down the coast were forced out of their government offices, had their businesses shuttered and their lives threatened.

All the significant gains black North Carolinians had made during Reconstruction were shattered by an explosion of white violence and intimidation in Wilmington in 1898, but on the isolated northeast coast it was still possible for members of the black community to go about their lives.

Supporter Spotlight

Much of the reason had to do with the opportunity then provided on the Outer Banks for dignified and well-respected jobs in the U.S. Lifesaving Service.

“So many African Americans ended up serving at Pea Island,” said Joan Collins, a Roanoke Island resident who has multiple family connections to the station.

Collins credits those early employment successes for the decades of subsequent achievements by generations of her family in the Coast Guard, the National Park Service and elsewhere in public service, including elected offices, on the Outer Banks.

Although Pea Island, situated on a remote stretch of Hatteras Island beach, was the only station in the nation with an all-black crew, white and black surfmen at all the Outer Banks life-saving stations routinely worked side by side on rescues, Collins said.

With descendants of the Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony, a Civil War-era settlement of freed slaves, long ago setting up homes on the island, the black community at the turn of the century largely coexisted peacefully with whites.

Supporter Spotlight

When Orville and Wilbur Wright arrived on the Outer Banks in the early 1900s, they would have seen black people participating in everyday life at the bustling Manteo waterfront, says Larry Tise, author of “Circa 1903, North Carolina’s Outer Banks at the Dawn of Flight,” published last year by the University of North Carolina Press.

When Orville and Wilbur Wright arrived on the Outer Banks in the early 1900s, they would have seen black people participating in everyday life at the bustling Manteo waterfront, says Larry Tise, author of “Circa 1903, North Carolina’s Outer Banks at the Dawn of Flight,” published last year by the University of North Carolina Press.

There would be black farmers hauling produce in wagons, black fishermen at the docks loading fresh catch onto vessels and black men offering visitors rides over water or land to their destinations, as Tise writes.

Yet, just 35 years after the Civil War, he adds, there was a “dangerous undercurrent of hate” between the races in coastal Carolina, a “massive, mean and often harsh rearrangement in the conduct of human affairs.”

The years between 1900 and 1908, when the Wrights made the majority of their Kitty Hawk visits, was “exactly the time North Carolina transformed into a white supremacy state,” Tise said during an interview before his presentation in January at the Coastal Studies Institute in Wanchese about his book.

The Wright brothers chose the Outer Banks to test their flying machines not only for the steady wind here, but also for the remoteness — the brothers were famously private and suspicious of sneaks stealing their secrets.

But Tise said the Outer Banks in fact had a remarkable network of infrastructure — lighthouses, river lights, ferries, canals, life-saving stations — that made it possible to move goods and people to and from the barrier islands and other coastal ports in a matter of days.

“It was an infrastructure equal to any on the East Coast,” he said. “In 1900, the reason why the coast was so commercially successful is because they could ship. It could be in Washington, D.C., the next day.”

So, despite the perception of being cut off from the world, the barrier islands were quite interconnected and not immune from outside influences — including the toxin of racism.

In the wake of the devastating 1896 Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson that allowed “separate but equal” schools, transportation and other public provisions, the Wrights arrived on the Outer Banks just about when segregation was seeping into everyday life.

The Wrights were prolific letter writers and diarists, but there is not a single mention of segregation or unequal treatment of blacks in their writings, Tise said. That could be attributed to the brothers’ singular focus on flight, he said, or it could be that racism was simply not notable. After all, their hometown of Dayton, Ohio, had already been segregated for several years. At the same time, the Wrights included no blacks in any other of the many photographs they took on the Outer Banks, nor is there evidence that they later employed blacks in their airplane manufacturing company.

When the Wrights returned to the Outer Banks in May 1908 to test an improved airplane, Tise writes, the attention they earned from reporters was shared with an event held on the north end of Roanoke Island at the site of the first English settlement in 1587. Better known as the “Lost Colony” because it not only failed, but also because no one knows what happened to the more than 100 settlers, the site is now part of the Fort Raleigh National Historic Site.

In 1908, Tise writes, many people came to commemorate the birth of Virginia Dare, where a granite marker noted it as the spot where the “English race” first settled. Speaking to the crowd, Francis D. Winston, the lieutenant governor at the time, declared the “planting” of the white race with the baby’s birth on Aug. 18, 1587, there was “heard the cry of an infant child, of pure Caucasian blood, declaring the birth of the white race on the western hemisphere.”

Honorable public service

Meanwhile on the Outer Banks, members of the Collins and Berry families — Joan Collins’ ancestors — were honorably doing their jobs as lifesavers and later, as Coast Guardsmen.

In 1896, Pea Island Life-Saving Station keeper Capt. Richard Etheridge, a former slave born on Roanoke Island, led his all-black crew in a daring and successful rescue of all passengers and crew of the three-masted schooner, the E.S. Newman, during a raging hurricane. One hundred years later, the crew was posthumously awarded a gold U.S. Lifesaving Medal that had been denied them during the Jim Crow era.

Collins, who serves as secretary of the nonprofit Pea Island Preservation Society, said her father, Herb Collins, worked at the station when he was in the Coast Guard, the successor of the Lifesaving Service. He also turned the key for the last time when the station closed in 1947.

In addition, her great-great-uncle was a member of the crew during the Newman rescue, her great-great-grandfather had served under Etheridge in the years after the rescue and her great-uncle was the last black keeper at Pea Island.

Many of Collins’ cousins and uncles had also served in the Coast Guard, giving her family boasting rights of having the longest-serving members of the service among the Outer Banks’ black community.

Later, her grandparents, Marshall and Gussie Collins, managed to accrue about 300 acres of land on Roanoke Island. The family donated a large portion to Dare County, which is where the county administration buildings and the county courthouse are today.

Collins said her grandparents, who had 10 children, struggled financially, even though Marshall Collins had worked as a farmer, a fisherman and substitute surfman at Pea Island. But he was entrepreneurial and was determined to leave land for his children.

Joan Collins, who today lives in a home built on her family’s land, said her late father, Herb Collins, was forever grateful that he followed her grandfather’s advice to join the Coast Guard.

“He loved the experience of being in the service,” she said. “It opened the doors for him when he was growing up.”