The U.S. Department of Interior Secretary’s reversal of a rule that limited where sand within federally restricted coastal zones may be placed is a change that makes good economic sense, proponents say, but one that environmentalists say is a step backward in protecting sensitive coastal resources.

Interior Secretary David Bernhardt announced late last year that federal funds can be used to pay for dredging sand within Coastal Barrier Resources Act units and then placing that sand on beaches outside of CBRA zones for shoreline stabilization projects.

Supporter Spotlight

Bernhardt’s decision overturns a 1994 Interior Department solicitor’s opinion, which concluded that in order to qualify for federal funds, sand in a CBRA zone had to stay within that CBRA zone.

His decision also overrides a 2016 interpretation by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which “stalled” and “ballooned” the costs of coastal storm damage reduction projects, “despite the Service in 1996 having previously allowed sand recycling” from certain CBRA units, according to a letter signed by three congressmen, including U.S. Rep. David Rouzer, a Republican from North Carolina’s 7th District.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Director Aurelia Skipwith said in a telephone interview last week that the department decided to reassess the interpretation of the act after receiving comments from those on Capitol Hill speaking on behalf of their constituents.

“And that fits along with what this administration, the Trump administration, is doing and what (Bernhardt) is focused on, which is using strong science looking at the rule of law to make sure that we’re looking at the policies that are impacting the communities that we’re working in,” she said. “As long as we’re following the law and the exemptions that are there, the sand that is within the system can be used for certain nonstructural projects outside of the system.”

Skipwith said each project will be analyzed on a case-by-case basis, “so long as the project furthers the purpose of the act and meets the act’s criteria, which are: One, it must be something that’s nonstructural; two, be for the purpose of shoreline stabilization; and three, it must mimic, enhance or restore natural stabilization. Then, those projects can be considered.”

Supporter Spotlight

Congress passed CBRA, which is pronounced “cobra,” in 1982 to discourage building on relatively undeveloped, storm-prone barrier islands by cutting off federal funding and financial assistance, including federal flood insurance.

CBRA was also established to minimize the loss of human life, wasteful spending of federal funding, and damage to fish, wildlife and other natural resources associated with coastal barriers.

In 1996, Fish and Wildlife granted exemptions allowing the Army Corps of Engineers to take sand from CBRA units in New Jersey and use that sand to renourish that state’s beaches outside of those units.

Similar exemptions have been made in North Carolina.

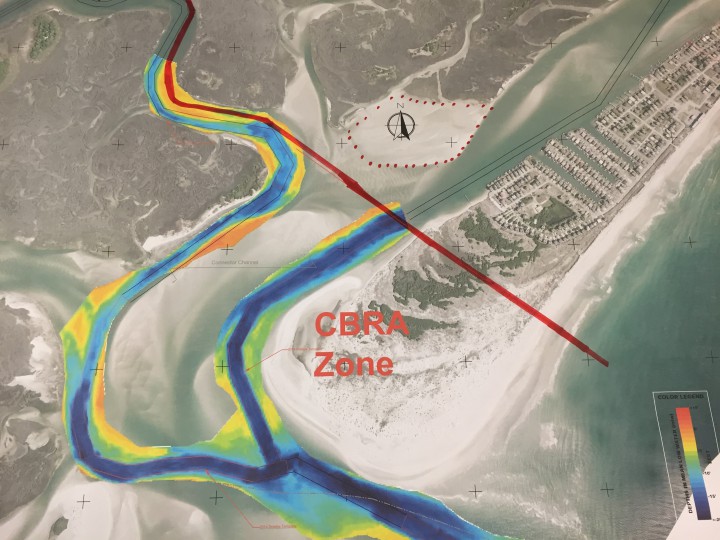

The Corps dredges Masonboro and Carolina Beach inlets to maintain their respective navigation channels. A portion of Masonboro Inlet and all of Carolina Beach Inlet are in Coastal Barrier Resources System Unit L09.

Sand within that unit has over the years been placed on both Wrightsville Beach’s and Carolina Beach’s ocean shorelines, projects paid for with local, state and federal money.

Dave Connolly, public affairs chief of the Corps’ Wilmington District, explained in an email responding to questions that Corps and Fish and Wildlife officials established an agreement that allowed the Corps to dredge and move sand outside of the CBRA unit.

“When the cost sharing agreements were originally entered into with the local sponsors of the Carolina Beach and Wrightsville Beach [coastal storm damage reduction] projects, it was generally understood in and agreed that the periodic maintenance of the projects was consistent with the relevant CBRA exceptions,” he said.

Then, Fish and Wildlife released its 2016 interpretation.

“Although the agencies never successfully resolved their disagreement, the Corps continued to maintain the projects in accordance with prior authorizations,” Connolly said. “When the respective projects required additional authorization in order to continue, the Corps agreed to pursue the investigation of alternative offshore borrow sources. [Department of Interior’s] reversal of their prior interpretation allowed the Corps to consider the inlet as a borrow source as well.”

Bernhardt’s reversal now opens the possibility for Topsail Beach, the southernmost town on Topsail Island, to get permission to tap a sand source within a CBRA unit rather than an offshore borrow source, something the town has been asking for the past decade, said Chris Gibson, the coastal engineer hired by the town to oversee its dredging and renourishment projects.

“At this point, I don’t know whether or not the town will push that simply because it’s so many years of study,” said Gibson, president of TI Coastal.

The town in 2010 initiated a project aligning dredging New Topsail Inlet with beach renourishment to cut costs.

Banks Channel, a navigable connector to Topsail Inlet and part of which is in a CBRA unit, has been the go-to sand source for beach renourishment projects in Topsail Beach, where the beachfront has been injected with more than 2 million cubic yards of sand within the past several years. More than half of that sand has come from the CBRA zone.

“This program is working in ways that other programs aren’t working,” Gibson said. “Why wouldn’t we do this?”

He said the timing of the Bernhardt’s decision bodes particularly well for the town because it continues to gain ground as the inlet steadily migrates south and farther into the CBRA zone.

Opponents of the reversal say the new interpretation may harm these ecologically sensitive areas, promote development in storm-prone coastal areas and reroute federal funding.

Karen Hyun, National Audubon Society’s vice president for coastal conservation, said that Audubon is not against beach renourishment projects, but sees protecting CBRA units as important to the integrity of those areas.

“I don’t know how many communities out there would like to use that sand,” she said. “CBRA expands the country’s 3½ million acres (in the John H. Chafee Coastal Barrier Resources System). I don’t think we understand the breadth of those impacts to all of those places. I think we have a lot of questions on how it will be implemented that meet the purposes of the act.”

Jim Herstine, professor emeritus at the University of North Carolina Wilmington and whose research includes coastal access issues, said removing sand from CBRA units will have damaging environmental impacts.

“When you give people an open chance to dip into sand any place where you can find it you’ve got to be hurting the areas where they’re coming from,” he said. “The sand has stayed within those systems. I think the issue of the fact is there’s such a finite supply of sand available to us now.”