To my Swedish-American father-in-law, Karl Hanson.

He would have made a good fisherman if he hadn’t been born in Kansas.

Supporter Spotlight

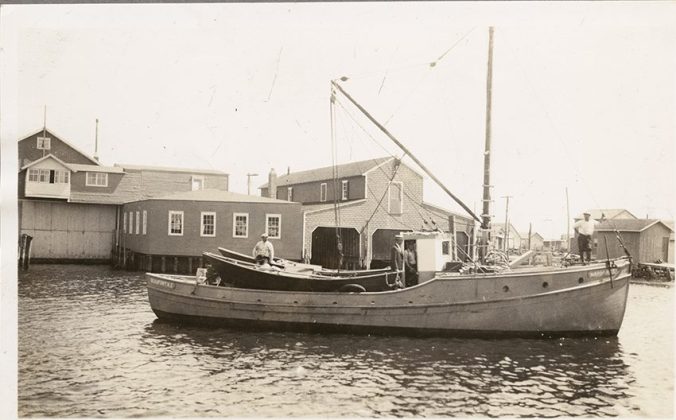

In this photograph (above), we see the blackfish boat Margaret at an unidentified port, probably in southern New Jersey, in 1934. Standing in the bow is Capt. Einar Neilsen, a Norwegian immigrant. He followed the blackfish, also known as tautog or black sea bass, north every summer, but he always returned home to Beaufort, North Carolina, for the winter.

Capt. Neilsen was part of a largely forgotten enclave of Norwegian, Swedish and Dutch fishermen and their families that left New Jersey and made their homes in Beaufort beginning in the 1910s.

Several other historical photographs of Capt. Neilsen and the Margaret shed light on Beaufort’s Scandinavian and Dutch fishing community.

In this photograph (below), Capt. Neilsen is standing at the stern of the Margaret while she is on a boatyard’s railway either for a repair or some kind of routine maintenance, also in 1934.

Both of those photographs come from the National Fisherman Collection at the Penobscot Marine Museum in Searsport, Maine. Both were taken while Capt. Neilsen and his crew were fishing up north.

Supporter Spotlight

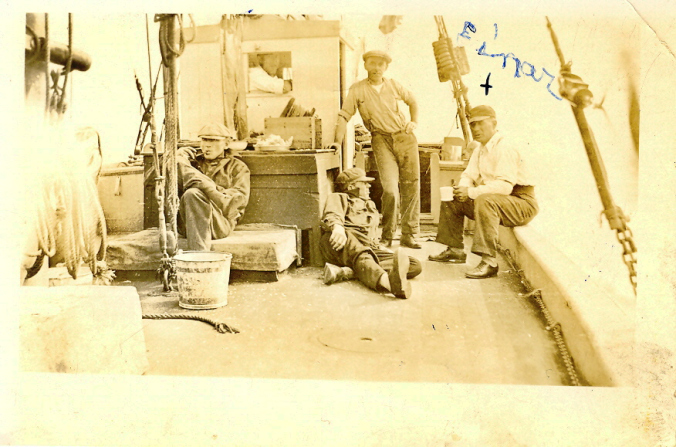

In a third photograph (below), provided to me by one of Capt. Neilsen’s grandnephews in Beaufort, the captain (far right) and crew are lounging on the deck of the Margaret.

I love this photograph, but I am not sure if Capt. Neilsen and his crew are in Beaufort, where they fished for blackfish in the winter, or in Wildwood, New Jersey, where they fished for blackfish in the summer.

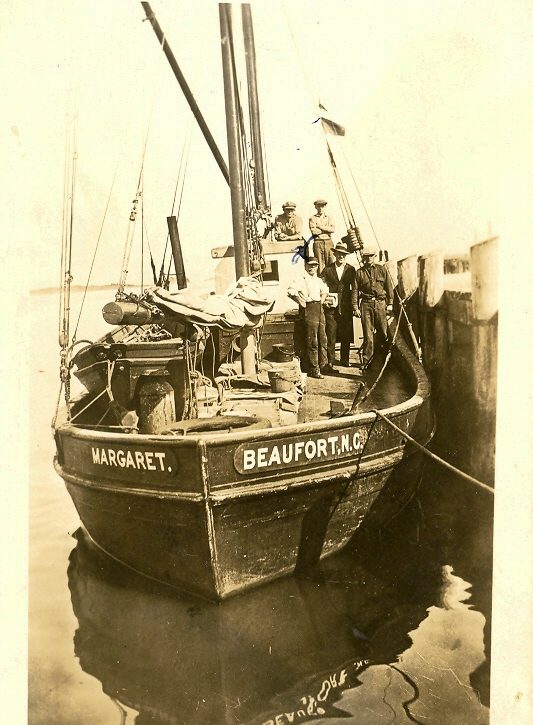

In a fourth photograph (below), also from Capt. Neilsen’s family, he and his crew are standing on the Margaret next to a wharf that is believed to have been in Beaufort. His brother Pete Neilsen is standing on the far left. Another Norwegian fisherman, Chris Hansen, is on the far right.

In our fifth and final photograph of the Margaret (below), likewise provided to me courtesy of Capt. Neilsen’s family, the captain is sitting on a pail on the bow of the Margaret with his crew. At that time, they were probably at their summer fishing harbor in Wildwood.

Next to the Margaret, we can see the Alice, his brother Thomas Neilsen’s somewhat smaller blackfish boat.

The Immigrants

According to a wonderful article that folklorist Michael Luster wrote for the N.C. History Council’s journal Tributaries in 1991, the first blackfish fishing crews left New Jersey and came south to Beaufort in 1913. They included several Swedes and Norwegians, as well as a Dutchman named Jess Pagels.

Other Scandinavians and another Dutch fisherman or two soon followed them to Beaufort.

The Norwegian brothers Einar, Thomas and Pete were among the first to leave the fishing grounds of southern New Jersey and follow the blackfish south to Beaufort.

Escaping hard economic times and looking for a brighter future, more than 800,000 Norwegians immigrated to America between 1825 and 1925, that amounted to one-third of Norway’s population. Only Ireland lost a greater percentage of its population to the U.S.

While most Norwegian immigrants settled in the Upper Midwest, a significant number also ended up in Brooklyn (especially the Bay Ridge neighborhood) and some of them eventually found their way to the fishing communities of southern and mid-coast New Jersey—to towns such as Wildwood, Barnegat Light and Atlantic City.

Norwegians moved to other fishing ports as well. Immigrants from the Norwegian island of Karmøy, for instance, made up a tremendous part of the scallop fleet in Fairhaven and New Bedford, Mass.

The Blackfish Boats

Einar Neilsen and his brothers were among the Norwegians that settled in Wildwood, New Jersey, and that’s apparently where they first grew familiar with the blackfish fishery.

Blackfishing was not dissimilar to other kinds of hand-line fishing that were common in the North Atlantic all the way from Scandinavia to New England, including the famous cod fishery on Georges Bank.

Then as now, large numbers of blackfish congregated on hard bottoms miles off the coasts of both New Jersey and North Carolina.

Fishermen made the trip offshore in tough, seaworthy vessels such as the Margaret. When the boat reached the fishing grounds, the crew launched several dories. In our first photograph (at the top of this page) you can see the dories stacked on the Margaret’s deck.

The fishermen jigged for the blackfish with hand lines from the dories and returned to the mother boat with their catches.

That’s why the Margaret has that distinctive, double-ended design. Unlike any other large fishing vessel constructed on the North Carolina coast in that day, she was built for the open sea and did not need a rounded or square stern since the Norwegian fishermen were not dragging a trawl, running a long line or hauling a dredge from the back of the boat.

The Margaret was built in Beaufort in 1922, almost certainly at the Whitehurst & Rice Boatworks that used to be located at the end of Ann Street.

That shipyard’s builders were capable, were not at all wedded to local “rack of the eye” boatbuilding traditions and are known to have built at least one other blackfish boat.

They turned out vessels as varied as menhaden boats, sharpies and pleasure boats for New York yachtsmen.

When they built the Margaret, the shipwrights at Whitehurst & Rice apparently copied the design of the blackfish boats that the Scandinavians and Dutchmen first brought south from New Jersey.

A New Home in Beaufort

Capt. Neilsen and the other Scandinavians discovered Beaufort by following the blackfish south. With their fair hair, thick accents and unusual boats, they must have made an impression.

So did their practice of fishing so far out in the Atlantic. Local fishermen did very little offshore fishing in those days.

Most of Beaufort’s commercial fishermen worked in local sounds and rivers. Even in the menhaden fishery, by far the town’s largest fishing industry, the boats rarely ventured more than a few miles into the Atlantic.

Rumors of blackfish grounds south and southwest of Beaufort Inlet had circulated in the local fishing communities for some time, however.

Then, in 1913, the Fish Hawk, a U.S. Fish Commission research vessel, surveyed the local offshore fishing grounds.

That survey found six major blackfish grounds on coral reefs or shell bottom 18-20 miles offshore in a line roughly parallel to the shore and running west from a point almost due south of Beaufort Inlet.

The first Norwegian, Swedish and Dutch fishermen showed up that same year. At first, they probably continued to live in New Jersey and just came south for the blackfish season in the wintertime.

Before long, however, at least some of those fishermen were calling Beaufort home, joining local churches and sending their children to the local schools.

One of my mother’s closest friends in Beaufort High School’s class of 1945, in fact, was Margaret Hansen, one of the Scandinavian fishermen’s children.

“The smartest girl in school,” our friend Betty Motes, who was also in the class of ’45, told me the other day.

While living in Beaufort, the Scandinavian fishermen still returned to Wildwood in the summertime for the blackfish season up there. While fishing out of Wildwood, they may have stayed with relatives or they may have slept on their boats.

As Michael Luster noted in his Tributaries article, they were not the only Beaufortites that fished out of that part of New Jersey in the summertime.

They must have run into many of Beaufort’s menhaden fishermen, too. Many of the town’s menhaden boats also worked out of fishing towns on that north side of Cape May during the summer.

The Blackfish Fishery’s Last Days

Beaufort’s blackfish fishery faded out in the late 1930s and early 1940s. The two big local fish dealers, Way Brothers and J. H. Potter & Son, had always sent the local blackfish catches almost exclusively to New York City, but the market vanished during the Great Depression.

Many of the Scandinavians remained in Beaufort and found other ways to make a living: some in the fishing business and others as painters and in other trades. Many of their descendants are still an important part of the community.

When Michael Luster was researching his 1991 article, the last of the Scandinavian and Dutch fishermen had already passed away, but he interviewed quite a few of their children.

Similarly, as I looked to understand the blackfish fishery better, I learned a tremendous amount from two of Capt. Thomas Neilsen’s grandsons, Tom Miller and Buddy Hansen.

Their grandfather was one of Capt. Einar Neilsen’s brothers. As I mentioned earlier, Thomas Neilsen was captain of the blackfish boat Alice that we can see tied up next to the Margaret in one of the photographs above.

In conclusion, I can only say that I never cease to marvel at the ways that the sea has connected my home state’s smallest ports and most out-of-the-way fishing villages to the rest of the world, including even the chilly, far-off shores of Norway, Sweden and Holland.

Note from the author: Special thanks to Tom Miller and Buddy Hansen for so generously sharing their family’s history with me. It was a great pleasure to learn from them. I’d also like to thank Mike Alford and Steve Goodwin for their help in researching the Margaret, and Steve Anderson for finding the Scandinavian families in the U.S. Census records at the History Museum of Carteret County in Morehead City, N.C.

I also cannot thank Michael Luster enough for his exceptionally well-researched article, “Fair Hair and Blackfish” that appeared in the October 1991 edition of the N.C. Maritime History Council’s journal, Tributaries.

In addition, I want to thank Douglas Arthur Wolfe, formerly of the NOAA lab in Beaufort. His book “A History of the Federal Biological Laboratory at Beaufort, North Carolina, 1899-1999” was indispensable to understanding the surveys of the blackfish grounds off Beaufort in the early 1900s.

Finally, I want to thank the Penobscot Marine Museum in Searsport, Maine, for permission to publish the two photographs of the Margaret.

Coastal Review Online is featuring the work of historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.