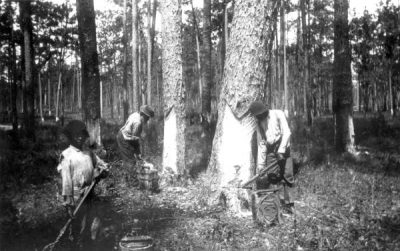

“The typical turpentine laborer in Wiregrass Georgia in the 1870s was a young, single … black man from North Carolina.”

I found that sentence in Robert B. Outland’s Ph.D. dissertation, which later became his pioneering book, “Tapping the Pines: The Naval Stores Industry in the American South,” published by LSU Press in 2004.

Here in North Carolina, naval stores meant turpentine, tar, pitch and rosin. Produced from longleaf pine forests, they gave North Carolina its nickname, “The Tar Heel State.”

Supporter Spotlight

Outland’s work chronicled the rise and fall of the naval stores industry, but what really grabbed my attention was this reference to a great migration of North Carolina’s turpentine workers to the naval stores industry in Georgia after the Civil War.

About one group of Georgia’s naval stores workers, he wrote:

“Of 178 turpentine laborers working at (turpentine) camps along the Macon and Brunswick railroad in 1879, 80% were black … and 70% were born in North Carolina.”

Most of those turpentine workers were young, single black men, and many of them had been born in slavery.

African Americans were not the only naval stores workers that went south, though. A large number of black, white and Native American people produced turpentine, tar, pitch and rosin in North Carolina. Many of them all left the state and went south after the Civil War.

They didn’t just go to Georgia’s forests, either.

Supporter Spotlight

After the Civil War, they had gone first, in any numbers, to South Carolina’s pinelands, and then to Georgia’s.

Following the pines, they scattered next across the southern states all the way from the Florida Panhandle to East Texas.

Their exodus tells us a great deal about North Carolina’s coastal history if we think about who they were, why they left and where they went, which is what I want to do in today’s post.

The Longleaf Pine Forest

My starting point is the great longleaf pine forest that once covered an estimated 4 to 5 million acres of North Carolina’s coastal plain. That forest was the foundation of the turpentine trade and the rest of the naval stores industry.

The longleaf pine tree (Pinus palustris) once dominated the forests of coastal North Carolina and it was the source of all of the state’s naval stores — turpentine, tar, pitch and rosin.

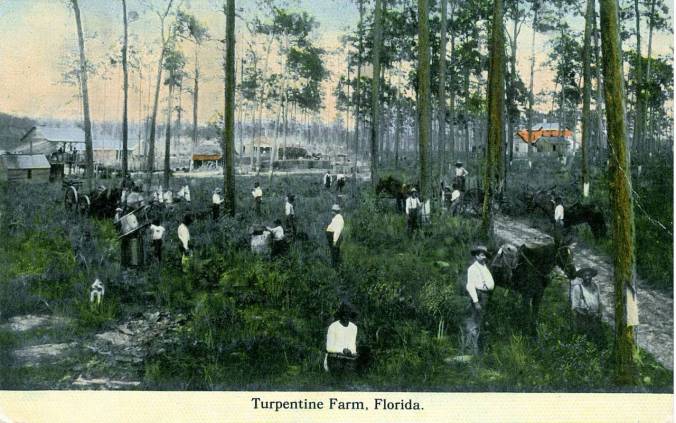

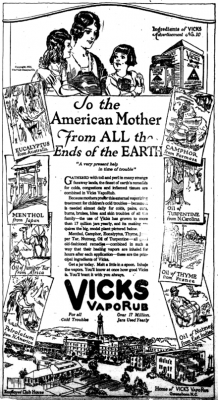

From the longleaf pine’s sap, naval stores workers produced turpentine and rosin by chipping off V-shaped sections of bark and collecting the trees’ gummy resin as it oozed out of the tree.

They then distilled that resin to produce “spirits of turpentine,” which in New York markets was sold in at least 10 different grades, each with its own use. Rosin was a by-product of that distillation process.

By burning the longleaf pines’ fallen limbs and other deadwood in earthen kilns, they also produced tar and pitch.

In the Age of Sail, those naval stores were essential for making wooden sailing ships watertight and preserving their planking and lines. Navies and merchant fleets throughout the Western World relied on those products made from North Carolina’s longleaf pine forests.

Naval stores had many others uses, too. Turpentine, in particular, was valued as an illuminant and was widely used in lamps and streetlights in the days before petroleum’s discovery.

The Turpentine State

As every school child here is taught, North Carolina was the capital of the country’s naval stores industry for much of the 1700s and 1800s.

North Carolina wasn’t just the naval stores industry’s capital, it was practically the whole show.

Even as late as 1870, more than 95% of all naval stores produced in the U.S. came from North Carolina’s coastal plain. The bulk of it came from counties along the Cape Fear River.

By most accounts, North Carolina’s seaports were the largest naval stores exporters in the world, rivaled only by those on the Baltic Sea.

In fact, to the average man or woman on the street in London or Paris, tar and turpentine were in most cases the only things they knew about North Carolina.

To them we were “The Turpentine State” and later, of course, “The Tar Heel State.”

You can learn more about the history of North Carolina’s naval stores industry elsewhere in my writings, by the way, especially in “The Turpentine State” and “Pitch Pines and Tar Burners: A 1792 Account.”

From Richlands to Wilkinson’s Point

I’ve also written a couple of articles that might give you a sense of the size and variety of turpentine operations that were once on the North Carolina coast.

Some turpentine businesses were massive. One of the naval stores operations that I wrote about many years ago was a turpentine plantation in Onslow County, North Carolina, that covered more than 20,000 acres and required the labor of more than 100 enslaved workers.

That was the Averitt family’s Richlands plantation, the location now of the town of Richlands.

That article was called “Oldest Living Confederate Chaplain Tells All? Or, the Rise and Fall of the Richlands.” It first appeared in Coastwatch, North Carolina Sea Grant’s wonderful magazine, and then I did a longer version in Southern Cultures, the journal of UNC-Chapel Hill’s Center for the Study of the American South.

The other story was about a much smaller kind of turpentine producer. It was called “John N. Benners’ Journal: A Saltwater Farmer & His Slaves” and was posted a year and a half ago.

John N. Benners resided on a plantation at Wilkinson’s Point on the Neuse River in Pamlico County.

He was a very common kind of turpentiner. Farming was the plantation’s mainstay, but Benners and three or four enslaved men and women also did a little turpentine collecting, along with other enterprises such as logging and fishing, when they weren’t needed in the fields.

Based on Benners’ diary, none of them worked in his longleaf pine groves more than a few weeks a year. He probably sent the collected pine resin to New Bern by boat and sold it to a distillery there.

The Destruction of a Forest

As Robert Outland points out in “Tapping the Pines,” North Carolina’s dominance of the nation’s naval stores industry began to change drastically in the decades after the Civil War.

By that time, the industry was destroying the region’s longleaf pine forest. In a frenzied half century of exploitation, the state’s longleaf pine forest fell from an estimated 4 to 5 million acres to less than 60,000 acres.

Travelers began to describe train trips through eastern North Carolina’s pine forests in which they did not see a single tree that did not have the V-shaped scar that was characteristic of tapping.

Between 1870 and 1890, the state’s share of the country’s naval stores market plummeted from 96.7% to 21%.

The longleaf pine forest was succumbing to ax and hack, as well as to insect infestations and diseases caused by the weakening of trees due to being over-tapped.

As the forest faded, turpentine workers, naval stores companies and their barrel, tool and other suppliers left North Carolina and headed to the longleaf pine forests in other parts of the American South.

From Beaufort County to Mobile Bay, Alabama

Some left before the Civil War. As early as the 1840s, a number of turpentine planters left coastal North Carolina and moved as far south as Alabama and Mississippi in search of new longleaf pine forests, sometimes forcing hundreds of enslaved workers to go with them.

In “Tapping the Pines,” for instance, Outland discusses a turpentine planter named James R. Grist.

Grist and his father got their start in the naval stores business in the longleaf pine forests of Beaufort County, North Carolina.

As they used up that “turpentine orchard,” they invested in new longleaf pine lands closer to Wilmington, North Carolina, including a 6,000-acre stand of longleafs in Brunswick County.

As those longleaf groves declined in the 1850s, Grist searched for new pine lands again, this time in other states.

He eventually found them on the Fish River, near Mobile Bay, Alabama. Taken out of North Carolina, a hundred of his enslaved African Americans established a new turpentine plantation there.

A Different Kind of `Great Migration’

The migration — forced and otherwise — of North Carolina turpentiners to other southern states was a trickle in the 1840s and 1850s. After the Civil War, though, it became a torrent.

As they left the Tar Heel State, turpentiners resettled first in South Carolina, then in Georgia and Florida. For a half century, the large number of North Carolinians in those state’s turpentine camps was legendary.

As Outland writes in “Tapping the Pines”:

“It does in fact appear that North Carolina turpentiners and their descendants dominated the industry throughout the South in the late nineteenth century.”

As the decades passed, the longleaf pine forests in those Atlantic coast states declined, too, and the naval stores industry faded there, much as it had already done in North Carolina.

Some of the turpentine workers returned to their old homes in North Carolina. However, probably far more either stayed in Georgia or Florida and found other ways to make a living or strayed to distant cities during the Great Migration of southern blacks to the northern states.

Yet others uprooted again and followed the naval stores industry to Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana and Mississippi. Their longleaf pine forests were comparatively unexploited and the rapid construction of railroads was opening up new pine lands in those states.

Yet another generation later, a few of those turpentiners and their descendants made it all the way to the Piney Woods of East Texas, where the South’s great longleaf pine forests finally gave out.

Every experienced genealogist of the American South knows about this “turpentine trail.”

Again and again, genealogists trace family ancestry back along that path of the longleaf pines and the naval stores industry.

Those genealogists may start with a family that lives in Georgia or Mississippi or Texas today.

But following deeds, marriage records and other historical documents, they can often track a family’s ancestry step-by-step back across the southern states. In many cases, they end up eventually on North Carolina’s coastal plain.

Peonage and Prisons

Wherever turpentiners went, their life was not easy. They left North Carolina because times were hard, they had few other options and the naval stores industry was a life they knew.

But naval stores work was always oppressive. Before the Civil War, North Carolina’s turpentine planters used enslaved workers for a reason. The work was hard, insufferably hot and ill compensated.

Peonage, basically slavery, remained an issue for turpentine workers in Georgia and Florida, among other places, well into the 20th century.

At the time, many observers compared living conditions in those turpentine camps to antebellum slavery. Others compared turpentine camps to prisons.

Beyond the turpentine camps, the outside world was no picnic, either. When North Carolina’s turpentiners arrived at a little crossroads in the piney woods of South Georgia or the Florida Panhandle, they often faced open hostility and a world of dangers.

They were, of course, outsiders — immigrants and strangers. Whether black, white or Native American, they were often treated like second-class citizens and made to feel scorned and unwanted.

Yet they left their homes and came south anyway, so bad had things become in what was left of North Carolina’s longleaf pine forests.

Shadow Memories

The fates of those turpentiners makes me think about a larger problem that I often struggle with as I think about how best to tell the story of the North Carolina coast and its history.

Sometimes it’s a challenge to tell stories about the people who stayed, but I struggle much more to find and hear the voices of the people who left.

I mean, of course, people like so many of the the turpentiners and tar burners that followed the naval stores industry into other southern states and never came back home.

To me their stories matter, too, and I also find that their stories often shed a great deal of light on the places they left.

Of course, the turpentiners and tar burners were not the only people from North Carolina’s coast that left. Over the generations, far more people left than stayed.

The list of those that left North Carolina’s coastal plain is long: uprooted farmers, the victims of bank closings and land grabs during the Great Depression, whole villages that gave up after the ’33 storm (and a dozen other major storms too), thousands displaced by military base construction and many, many more.

And there were others — well, far too many of the people that lived here left these parts simply because they found this land too oppressive, and found us too close-minded.

All once belonged here, though, and I still think about them. I wonder where they all went and what became of them and where their descendants are now and how they are doing.

I wonder if their grandchildren or great-grandchildren have forgotten their roots here completely. I wonder if the old people still tell stories about us and life here on the North Carolina coast.

I wonder if they remember things that we don’t.

I wonder about simpler things, too. I wonder, for instance, if they still make cornbread like we do or if they put their children to sleep at night with the same lullabies that my grandmother sang to me.

I wonder if they get irresistible cravings for a plate of roast jumpin’ mullet when the prevailing winds shift in the fall, or for muscadine grapes in late summer, as so many of us do, no matter how far from home we may be.

I wonder what other longings they still feel, and what shadow memories they have somehow inherited, and perhaps hold somewhere deep in their bones, that go back to these shores and the once great longleaf pine forests that used to be here and are no more.

Coastal Review Online is featuring the work of historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state’s coast as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.