RALEIGH – A recent report from the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission recommends putting a state agency in charge of removing derelict and abandoned vessels in navigable North Carolina waters, with dedicated funding to address the problem.

In North Carolina, the legislature has granted limited authority to local governments and state agencies to determine how and when a vessel can be removed. But local officials continue to struggle with abandoned and derelict vessels in waterways and sometimes washed up on public or private lands, threatening navigation and the environment.

Supporter Spotlight

The North Carolina General Assembly in 2018 directed the WRC to provide the report by April 30 because of the growing concerns over abandoned vessels and to consult the Division of Coastal Management, North Carolina Coastal Federation, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Marine Debris program, marine salvage industry experts, commercial and recreational boat owners and other stakeholders.

“The report detailed many different approaches used by other states in the management of abandoned and derelict vessels. It also described some of the challenges other states face in the management of abandoned and derelict vessels based on their management practices and laws in their state,” Ryan Kennemur, public affairs specialist with the state Wildlife Resources Commission, told Coastal Review Online.

The report notes that the resource used as a starting point was current up to 2015 and the researchers reached out to each coastal and Great Lakes state included in the report to update, clarify and collect more data.

In addition to naming a lead state agency to manage the problem, the report also recommends establishing a WRC-coordinated task force for abandoned and derelict vessels, or ADVs, as well as enacting a law defining and addressing ADVs statewide with disposal options and vessel owner notification protocols and rights. The report also calls for establishing education, outreach and prevention programs, including a vessel turn-in program fashioned after those used by other states.

The WRC manages more than 200 boating access areas on public waters across the state and is the chief enforcer of boating safety laws in North Carolina. In addition, the WRC works with local governments to determine no-wake zones.

Supporter Spotlight

“The WRC also manages the placement of waterway markers in conformance with the uniform rules to aids to navigation for boating access areas and approved no-wake zones across the state,” Kennemur said.

The University of North Carolina Institute for the Environment and the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory were contracted to research how other states with navigable waterways manage abandoned and derelict vessels for the report.

Researcher Susan Cohen with the Institute for the Environment said that the WRC developed the report’s overall approach to address and meet the North Carolina legislative direction.

She explained that the Institute of the Environment provided a summary of abandoned and derelict vessel programs in coastal and Great Lakes states produced by using sources of existing, current information, including the NOAA Marine Debris Program, with follow-up communications with each of the states to confirm that information. “Other groups, like NOAA for example, have done a great job capturing state-level information and we just built off what these other efforts had accomplished,” she said.

According to the report submitted to WRC, An Overview of State Abandoned and Derelict Vessel Programs, no single federal law is in place to comprehensively address ADVs, especially if navigation hazards or pollutants are not an issue.

Depending on circumstances such as pollution and navigation threats, there are laws and regulations that give authority to certain federal agencies, including NOAA, which is the lead agency on ADVs, the Army Corps of Engineers, the Coast Guard, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Federal Emergency Management Agency, but for the most part, the responsibility ultimately falls on state and local authorities to manage the derelict and abandoned vessel.

“Our primary concentrations within the (report) summary were the status of legislation within each state, where decision-making authority to respond to ADVs lies, the resources expended by each state and the numbers of boats removed. This snapshot provides decision makers with a view of the broad range of strategies used by other states without being prescriptive to how North Carolina should respond,” Cohen added.

The report used NOAA’s “ADV InfoHub,” a website describing how ADVs are handled by each coastal state, as a starting point, compiling existing information on state programs and fact sheets for each state, current through 2015. The report acknowledged that since then, several states have enacted legislation and provided funding to support ADV programs.

The researchers sent a questionnaire by email March 8 with a follow-up March 15 to more than two dozen coastal and Great Lakes states, except North Carolina, to fill in gaps, update and gather information related to legislation, funding and measurable results from ADV programs. Of the 28 states that were contacted, 14 responded.

Results of the questionnaire show that other states typically do not keep detailed records on removed ADVs or funding. Many of those responding to the questionnaire were unable to give numbers on funding or removal efforts.

States that reported the greatest numbers of ADVs between 2013 and 2016 were Ohio, which has no allocated funding, at 1,400; Texas at 1,080; Florida at 824; California at 657; and Washington, which has a $2.5 million program that has removed more than 700 vessels since 2002, at 366.

Kennemur with WRC said North Carolina does not track the number of ADVs found each year.

The results point to a handful of issues that interfere with managing ADVs in waterways, including the challenge of finding vessel owners, the lack of recurring state funding in 20 of the 30 coastal and Great Lakes states and a lack of understanding as to what authorities are responsible for certain actions and preventive measures.

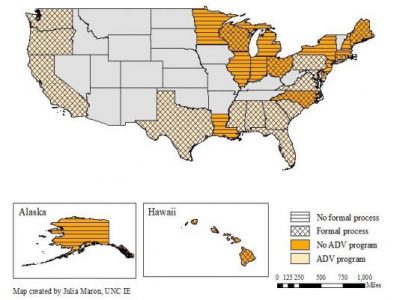

The report notes that of the 30 coastal and Great Lakes states, 29 had some type of legislation addressing ADVs, with 16 of those states having enacted legislation during the last 10 years. New York is the only state that hadn’t enacted ADV laws.

Also, of those 30 states, 21 have laws that include civil penalties for abandoning or failing to remove a vessel after notice. Twelve states impose criminal penalties for abandoning or failing to remove a vessel after being notified.

Six states have adopted a vessel turn-in program in an effort to prevent vessels that are older or in poor condition from entering the water and becoming an ADV. Although details vary by state, the program allows owners or marinas to turn over vessels to a state or agency for proper disposal at no cost.