DUCK — If there is one philosophy uniting the long string of communities along the Outer Banks, it is that their beaches should be open and free. And accessible.

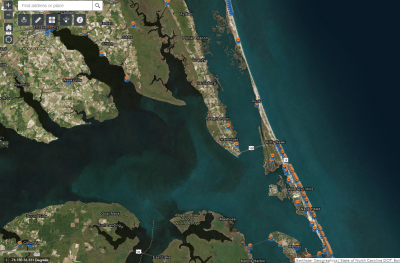

But the town of Duck is one of the few communities along the entire coast of North Carolina that provide no public access to the ocean shoreline. The adjacent town of Southern Shores also lacks public beach accesses, effectively cutting off a total of about 12 miles of ocean coastline on the northern Outer Banks to all but private property owners, renters and their guests.

Supporter Spotlight

That might be why the recent arrest of Duck resident Bob Hovey for using what a property owner contends is a private beach access in his neighborhood has ignited a firestorm on social media about private property rights versus public rights to access the beach.

“What it comes down to it is the closest access to my house,” Hovey said in an interview. “I feel like I should be able to use it.”

A confrontation between Hovey and two homeowners at the Sea Breeze Drive beach access in the Sand Dollar Shores subdivision on May 29 culminated in the owners calling the police on Hovey, who was arrested for trespassing.

In a Facebook video Hovey took and subsequently posted, a man and woman cursed at Hovey for using the access, while he responded that the access was deeded to the public in 1981. He also posted another video of police questioning his right to use the access to get to the beach to go surfing, which happened after police said that parking on the nearby street was not allowed.

Hovey has owned his home in the Osprey Ridge subdivision since 2003, but the access in question, which is across the street, is in a different subdivision. Property owners in the private subdivisions have rights to use designated accesses.

Supporter Spotlight

About two years ago, Hovey filed a lawsuit that has since been withdrawn against the town, claiming that the access and others in the town were deeded to the public in 1981. Hovey said he has a copy of the original plat.

“The beach is for everyone and something needed to be done to protect beach access rights in Dare County,” Hovey said in a Facebook post. “The town of Duck has received millions of Dare County taxpayer money for beach nourishment and other beach services.”

But Hovey’s business, Duck Village Outfitters, in operation off Duck Road since 1998, involves rentals of equipment for the beach and recreational water activities, which has perhaps made him more aware of the value of beach access.

“I’ve been doing deliveries and surfing in Duck more or less for 23 years,” he told Coastal Review Online. And as a surfer, he wants to check different places on the beach for waves. “I own a surf shop in Duck and I’m not allowed to access the beach to surf in Duck.”

The situation with no public beach access to Duck’s 7 miles of ocean shoreline had existed prior to when the town was incorporated in 2002, said Town Manager Chris Layton. Only three subdivisions in the town don’t have deeded beach accesses associated with them, he said, and they were approved before or during the town’s incorporation.

“The town doesn’t own or maintain any access point (to the ocean) in Duck,” he said. “But getting to the beach has not been an issue.”

In his 17 years as manager, Layton said, Hovey is the only person who has officially complained to the town about the lack of a “traditional” public beach access. The town manager said that there have been “many, many, many” calls to police over the last four years about Hovey trespassing.

The town council has not gone beyond passing discussions about creating a public access, he added, and there has been no state requirement to do so. “The opportunity has not presented itself in a way where the town thinks we need to move forward.”

With nearly all available land in private developments, except for the federally-owned Duck Pier, Layton said that for the town to provide an access – short of exerting eminent domain – it would require the town to purchase expensive oceanfront land, or depend on a donation from a private property owner. But he said the town is open to exploring a way to create an access if that’s what the public wants.

“The challenge for the town would be to go in and retrofit public access points,” he said. “That’s a lot more complicated than people believe it is.”

All the accesses – about 40 or so 20-foot corridors – along Southern Shores’ nearly five miles of beach are owned and maintained by the Southern Shores Civic Association, said Peter Rascoe, the town’s manager. And that was how it was even before the town was incorporated in 1979, he said.

Rascoe said that the issue of public access has not been raised.

“I guess there’s never been any conflict to force a discussion,” he said.

The state Department of Coastal Management provides about $1 million a year in matching grants to local governments for public beach access projects and improvements. The funds can also be used to help acquire land needed for access sites.

The Outer Banks chapter of The Surfrider foundation, a national nonprofit environmental group that advocates for open beach access, is currently going through a transition and is looking for a local volunteer to work on the issue, said Ivy Ingram, chapter chair.

“Unfortunately, our chapter is currently overwhelmed and needs help in order to take on any more issues including the Duck access issue,” she said in an email. Anyone interested in volunteering can contact the group at outerbanks@surfrider.org.

Municipalities that use public funds to nourish beaches – as Southern Shores and Duck have done – are required to provide public beach accesses. But Rascoe and Layton claim the requirement only applies to federal funds. The projects were funded by county and municipal funds.

But attorney Norm Shearin, a partner in commercial law firm Nexsen Pruet in Raleigh, disagreed.

“It doesn’t matter where the money comes from,” he said. “It does not have to be federal money. It just has to be public money.”

Shearin had previously represented Hovey in filing lawsuits against the town, which has been dismissed after Hovey’s request, and the homeowners’ association, which was dismissed by the judge, but he is only now helping as a consultant. In the legal challenges, the town of Duck had sided with the property owner in arguing that the beach accesses in the town were privately deeded.

But the town’s position, Shearin said “pays lip-service” to public access. Under North Carolina law, the public trust area is below the mean high water.

“Obviously, you’ve got to get to the interior area to get out to the ocean,” he said. “The public trust rights would be meaningless if they were just lateral along the oceanfront.”

Power companies and other public services possess “secondary use rights” to access, he said, but the right to access the beach has not been litigated in the state.

“The public trust rights are still being defined in North Carolina,” he said.

Hovey, meanwhile, is trying to raise funds to hire a local attorney. But he holds out hope that a reasonable solution can be worked out with the town.

“At this point, it’s still in motion,” he said. “Hopefully, we can get some negotiation (to resolve it) without a costly court procedure.”