Despite names worthy of Roald Dahl characters, few people know of the two odd creatures who inhabit Piedmont river basins in North Carolina, and even fewer have seen them. But environmental scientists say the Carolina madtom, a small, spotted catfish with spiky, venomous spines, and the Neuse River waterdog, an aquatic salamander with impressive flame-like gills, are vital to the balance of the Tar-Pamlico ecosystem. And their future could be in trouble.

In response, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is proposing to add special protections for both animals under the Endangered Species Act with the madtom proposed to be listed as endangered and the waterdog as threatened.

Supporter Spotlight

The decision to list the madtom and the waterdog was reached after species status reviews found steep declines in their abundance and range in watersheds they occupied historically, although population estimates are not possible, said Sarah McRae, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service aquatic endangered species biologist.

“They’re hard to sample for,” she said. “It’s more a presence/absence thing.”

McRae said the two species were named in a 2010 petition submitted to the Wildlife Service by the Center for Biological Diversity and others requesting the listing of 404 aquatic species in the Southeast. As part of its response, the agency subsequently found that there was enough information to indicate that listing may be warranted for the madtom and the waterdog, which was confirmed by further review.

In comparing occurrences over time of the two species, both of which live in the Tar-Pamlico and Neuse River basins, biologists determined that the Carolina madtom had lost 64% of its historical distribution, while the Neuse River waterdog had lost 35%.

A species is defined as endangered when it is at risk of extinction throughout all or much of its range and as threatened when it is likely to become endangered in the foreseeable future.

Supporter Spotlight

Critical Habitat Designation

The agency is also proposing to designate about 738 river miles for the waterdog and about 257 river miles for the madtom as critical habitat, which would identify the biological and physical features that are important to their survival. The designation would not affect any landowner activities that do not require federal funds or permits. Federal agencies would be required to consult with the Wildlife Service on any activity that could harm the species or its habitat.

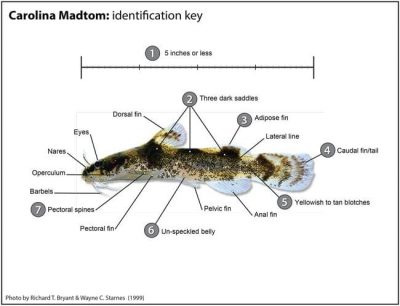

As the lead biologist in the species’ assessment, McRae became well acquainted with the two animals and their particular distinctions. The Carolina madtom, for instance, is one of numerous madtoms in the fish world, but it is chunkier and the only state native. And its venomous spine makes it notably nasty to encounter.

“It actually really hurts a lot if you get poked,” she said. “Most of the time, it’s in your hand, and it may swell a little bit. I am very, very careful — I try to avoid handling them.”

Only about 5 inches at maturity, the Carolina madtom is a non-game freshwater catfish that has none of the invasive qualities of its much bigger cousin, the flathead catfish. In fact, its favorite hangout is at bottom of rivers and streams, where it eats larval mayflies, midges and other invertebrates.

“It blends in very well,” McRae said. “Its strategy is it just stays there and blends in — which is a problem if something comes along — and just vacuums you up.” The flathead catfish, an omnivorous and prolific feeder, is considered a major threat to the Carolina madtom.

But the madtom, a sight feeder, has more problems than its greedy cousins. Declines in water quality — more sediment, nutrients and invasive weeds and less clarity — and water quantity have made some areas intolerable to the little fish.

“They’re in such drastic decline,” she said.

In its assessment, the Wildlife Service deemed the species to have limited resiliency, redundancy and low representation in its historic habitat — hence, the proposed Endangered Species Act listing. The “3 Rs” are the principles the agency uses to characterize a species’ current and future viability.

Increased nutrients from fertilizers and animal and human waste in rivers are contributing to decreased oxygen levels, overgrowth of invasive aquatic weeds like hydrilla and more frequent algal blooms in warm weather. But nutrients are one of myriad challenges, McRae said.

“Sediment is a big issue in our rivers,” she said. “Runoff washes off land and smothers the bottom.”

That ecological blight also threatens the amphibious waterdog for similar reasons, she explained.

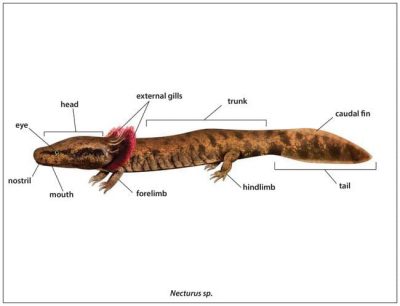

“The waterdog is a visual predator,” McRae said. “It needs to be able to see. It also has these feathery red gills outside its head that can be smothered.”

A cousin of the much bigger hellbender salamander, the Neuse River waterdog never leaves the water in the medium-sized streams to large rivers it inhabits. At a maximum 11 inches in length, the waterdog has stubby legs and a reddish body with large blue or black spots. Since it lacks lungs, it needs clean, flowing water for oxygen. Its presence, therefore, is a good sign for the surrounding environment.

“It’s indicative of clean water and good habitat,” McRae said.

The Wildlife Service’s assessment found that the waterdog has limited resiliency and moderate to low population representation and redundancy.

Climate change and increased urbanization are also a looming concern for both species. The waterdog, for instance, thrives in cold water and drastically reduces its activity when water temperatures rise above 45 degrees. Higher temperatures in river water are also associated with decline of the madtom.

Increased storm intensity caused by climate change can also increase silting and flush more pollutants into the waterways. On the flipside, climate-related droughts decrease water flow and increase concentrations of pollutants.

Dams, culverts and other water-control structures also limit movement of the madtoms and the waterdogs through the streams and rivers and slow water movement, resulting in less oxygen and compromised water quality. Agriculture and upstream development have altered the natural landscape and resulted in more runoff laden with sediment and contaminants.

If the Carolina madtom and Neuse River waterdog are listed as endangered species, the Wildlife Service will work with the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission and other partners on conservation and restoration efforts, including monitoring, surveying and land acquisition from land trusts.

Although the two species may seem to be insignificant players in the big scheme of life, McRae said they are an important part of a dynamic and interlinked aquatic food chain. And as one of few people to have encountered what she regards as “the coolest creatures, ” McRae said that the animals not only deserve to exist, but they also reflect the quality of the environment in which humans live.

“They are sensitive species that we need to pay attention to,” she said.

Learn More

- The Fish and Wildlife Service will accept public comments on the proposals through July 22.

- Or visit regulations.gov and enter FWS-R4-ES-2018-0092 in the search box to comment.