KURE BEACH – A study expected to be released later this month will give Kure Beach officials an idea of whether the town should pursue adding dune infiltration systems to further reduce the frequency and volume of stormwater discharging from the town into the ocean.

The study, funded through a Clean Water Management Trust Fund grant, will determine the feasibility of infiltrating stormwater at six ocean outfalls in the town.

Supporter Spotlight

“At this time the hope is that all six sites will have some size of dune infiltration system,” said Jonathan Hinkle, an engineer with Charlotte-based LDSI Inc.

Dune infiltration systems will work at all the sites, he said, but some areas may be better suited based on their proximity to infrastructure and those where dunes are highest, all of which will affect the cost to install the systems.

Installing infiltration systems at all six sites will cost up to an estimated $600,000.

Between 2005 and 2006, three dune infiltration systems were installed in the town, where more than a dozen stormwater pipes installed in the early 1900s divert rainwater from roads, roofs and lawns directly onto the beach and into the ocean.

The outfalls are identified by signs put up by the state warning beachgoers to steer clear of the areas where runoff, which can carry bacteria harmful to human health, sometimes pools onto the beach before it flows into the sea – not exactly the image any beach town desires.

Supporter Spotlight

So, Kure Beach and North Carolina Department of Transportation officials set out to find a way to reduce the frequency and volume of stormwater discharging into the ocean.

They teamed up with Michael Burchell, an assistant professor and extension specialist in biological and agricultural engineering at North Carolina State University in Raleigh and began to discuss their options.

“We were looking at some of the traditional ways that people mitigate stormwater,” Burchell said.

There was talk of building a large retention pond or creating bioretention areas. They discussed pumping stormwater to the back of the island and into the Cape Fear River. Those possibilities were simply not cost-effective, Burchell said.

He was standing on a beach crosswalk in town with transportation officials when the idea came to him – use the land between the dune and beach.

Burchell led the research team that designed a system that collects stormwater and filters bacteria.

The system works like this:

- Plastic open-bottom tubes buried underneath the dune collect diverted runoff.

- As those chambers fill, the water flows into a bed of gravel where the water spreads onto sand, which acts as a filter, diluting runoff before it reaches groundwater.

- Bacteria that gets trapped in the sand dies and when the runoff is 75 feet down shore bacteria levels are similar to that found in normal groundwater.

The results were better than expected.

Three consecutive years of monitoring showed that infiltration systems installed near L Avenue and M Avenue treated nearly all the runoff – 100% at one site and 96% at the other – collected from two discharge pipes that drained a total of 12 acres.

“That was way higher than we anticipated,” Burchell said.

“That’s huge,” said Lauren Kolodij, North Carolina Coastal Federation deputy director. “It’s a health issue. It’s a tourism issue. So, it’s really a priority to get that polluted runoff out of our waters. It serves as a model for other coastal communities.”

The infiltration system near the Kure Beach Pier and K Avenue is the largest of the systems, is buried deeper in the dunes and collects runoff from three outfalls.

The system at this site captured 80 percent of the runoff during the first year after it was installed.

“We acknowledge the fact we were not going to be able to capture every storm event,” Burchell said.

When bacteria levels in runoff from the ocean outfalls exceed water quality standards, officials with the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality’s Shellfish Sanitation and Water Quality issue public advisories, warning against going into waters near the outfalls because of potential health hazards.

Erin Bryan-Millush, Shellfish Sanitation and Water Quality supervisor, said the number of those advisories had dropped in Kure Beach since the infiltration systems were built.

“I have seen improvement,” she said.

Before the infiltration system was installed at the stormwater pipe near K Avenue, the state issued four swim advisories between 2004 and 2006.

Bryan-Millush said the only advisory the state has issued at that location since the system was installed was in August 2014, when rainfall dumped between 3.5 to 4 inches of water in a 24-hour period.

Caswell Beach Project Advances

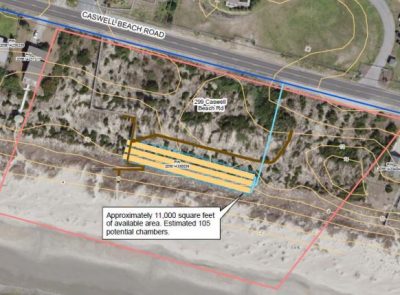

Caswell Beach in Brunswick County is planning to install 735 feet of dune infiltration system on town-owned land near the Oak Island Lighthouse.

During a presentation at the annual North Carolina Beach, Inlet and Waterway Association meeting in April, Marc Horstman, project manager with the civil engineering firm WK Dickson & Co. Inc., said large storm events in Caswell Beach flood the main road, making it impassable. It’s a common problem in towns on barrier islands up and down the North Carolina coast.

Caswell Beach’s project will cost an estimated $280,000, which includes relocating a boardwalk and installing a stormwater force main. Construction is expected to begin in September.

“I think this is a really neat technology and neat tool that we can start using up and down the coast,” he said. “In some cases it might work. In some cases it might not work. I think it’s just a tool for us to kind of start thinking about. We need to start thinking outside the box.”

Jennifer Allen contributed to this report.