This is another in a series of reports on coastal resilience.

WILMINGTON – Coastal towns and counties can now access an online tool that pinpoints areas where resiliency projects would best help communities in the face of storms, floodwaters and rising seas.

Supporter Spotlight

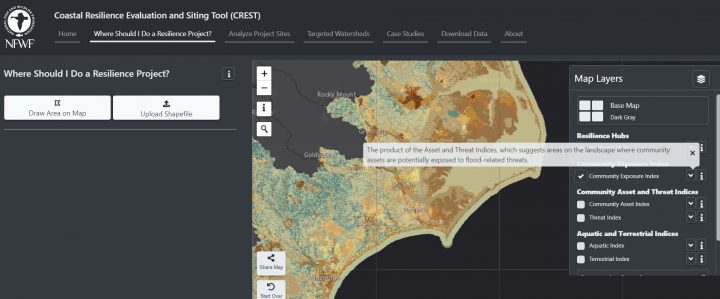

The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation earlier this month released its Regional Coastal Resilience Assessment along with a new Coastal Resilience Evaluation and Siting Tool, or CREST, that identify and rank potential project sites along the Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico and Pacific coastlines in the lower 48 states.

The assessment uses standardized, nationwide data that establishes an apples-to-apples comparison when it comes to evaluating potential resiliency projects, explained Mandy Chesnutt, NFWF’s director of program operations.

CREST takes the initial guesswork out of potential project areas by identifying so-called “resilience hubs.”

These hubs are areas of open space that surround dense population centers, are immediately accessible to infrastructure and host natural resources and habitats that provide protection to humans. They are also areas that are at the highest risk of flooding from coastal storms and sea level rise.

“It is one tool in our arsenal,” Chesnutt said. “The assessment is a starting point. It can give you a few of these hubs that you can go and check out. What we’re saying is, ‘use this tool as a starting point. You need to go out and investigate these places.’”

Supporter Spotlight

What makes NFWF’s assessment unique is that it targets areas where both humans and wildlife would receive the most benefit from natural resiliency projects, such as living shorelines and wetlands restoration.

Researchers, including those with the University of North Carolina Asheville’s National Environmental Modeling and Analysis Center, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and NatureServe, delved even deeper to identify potential project sites through targeted watershed assessments.

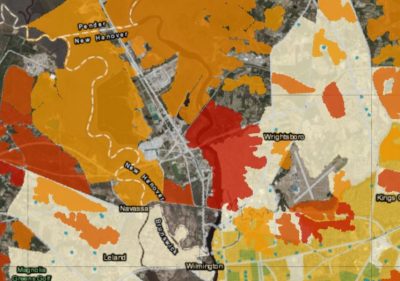

North Carolina’s Cape Fear watershed is among eight coastal watersheds from Maine to Florida and California included in the targeted assessment.

The Cape Fear watershed in 2015 was the first to be evaluated.

and Wildlife Index. Higher ranking indicates higher priority. Source: National Fish and Wildlife Foundation

This watershed supports more than a third of the state’s population – more than 2 million people – and stretches through nearly 30 counties and 114 municipalities, including Greensboro, Fayetteville, Durham, Chapel Hill and Wilmington.

The Cape Fear watershed is home to a wide array of habitat that supports juvenile fish, crabs, shrimp and a host of migratory fish as well as some of the oldest cypress trees in the world.

This was the testing ground on how to develop resilience assessment models, identify resilience hubs and rank those hubs.

One of the areas identified within the watershed is a patch of wetlands west of Wilmington International Airport.

Chesnutt said the wetlands’ proximity to a densely populated area paired with the fact it is host to a number of species, makes it a good spot for a restoration project that would create protection from storm surge and, at the same time, providing important wildlife habitat.

The idea behind identifying such sites is to give communities a starting point as to where to look for areas that would most benefit people and wildlife, said Dawn York, senior coastal scientist with Moffatt & Nichol and Cape Fear River Partnership coordinator.

“It’s work that’s already been done, so coastal communities can move beyond that first stage,” she said.

NFWF will use the assessment tool to evaluate proposed projects submitted annually from communities throughout the country for a piece of the National Coastal Resilience Fund, Chesnutt said, but towns and counties are by no means restricted from working outside of the areas identified in the assessment.

Each year, NFWF evaluates dozens of project ideas from communities vying for grant money from the $30 million fund.

“We have a really good sense of what we’re looking for,” Chesnutt said. “The competition is really fierce. We do try to distribute it evenly around the country.”

The foundation is not interested in projects that would include sea walls, jetties or other hardened structures, she said.

“It’s really focusing on those green solutions,” she said. “I think, in general, we are seeing a greater willingness to look at those natural solutions and not just hardened structures.”

Take the project initiated by Battleship North Carolina executive director, retired Capt. Terry Bragg.

The project known as Living With Water entails creating space for water pushed up the Cape Fear River by coastal storms and rising seas.

“They are taking action and that’s what we need to do,” York said.

The Cape Fear River Assembly has submitted a preproposal grant application for $125,000 from the National Coastal Resilience Fund for Creating a Resilient Wilmington planning project.

This is a stakeholder engagement project that will include Cape Fear River Assembly, the city of Wilmington, civil engineering firm Moffatt & Nichol and New Hanover County to “prepare for Wilmington’s next steps in the creation of its resilience strategy by improving upon its nature-based infrastructure including its wetlands, rivers and coasts.”

“We want to bring this urban planning effort to the city, but utilize that NFWF CREST tool,” York said.