HYDE COUNTY – In another of a series of ecosystem indignities for Lake Mattamuskeet, opening day of boating season on Friday was accompanied for the first time with posted signs warning of harmful algal blooms.

Commonly known as blue-green algae, cyanobacteria can produce toxins that can cause illness in humans and animals, including skin rashes, digestive disorders and respiratory distress.

Supporter Spotlight

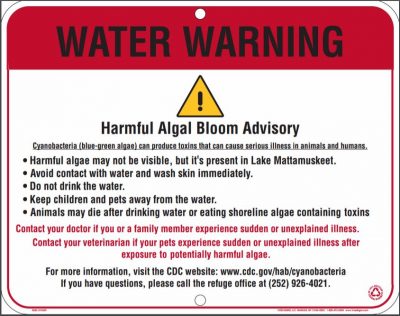

The signs, white with a bold red stripe at the top with the words “WATER WARNING,” advise people that harmful algae is present in Lake Mattamuskeet and to avoid contact with the water. The notices also warn against drinking the water and to keep pets and children away.

Pete Campbell, manager of Mattamuskeet National Wildlife Refuge, said that algal blooms have been an issue in the lake for the last few years, especially on hot days, and the conditions that cause the blooms have not been alleviated.

Campbell said the public should be aware of the potential health risks, as well as the ongoing efforts to restore the health of North Carolina’s largest natural lake.

“The message is you don’t have to avoid enjoying the lake, but take precautions,” he said. “We felt it prudent.”

Although the signs also say “animals may die” if the water or toxic algae is consumed, Campbell said he is unaware of any reports of pet or wildlife deaths from past blooms.

Supporter Spotlight

Swimming has never been allowed in the lake, Campbell said, but even incidental splashing or wading should be rinsed with clean water.

But it’s safe to eat fish caught in the lake, according to the refuge manager. Fish are plentiful in the lake, he said, including catfish, crabs, largemouth bass, black crappie and, to a lesser extent, white perch, sunfish and carp.

Studies have shown no bioaccumulation of toxins in fish, he said, and there are no documented cases where people have become sick from eating fish caught at Lake Mattamuskeet.

Cyanobacteria are photosynthetic, single-celled aquatic organisms, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. In freshwater, a harmful algal bloom can develop quickly and is more likely in warm, still waters with abundant amounts of nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen. Signs of algae contact include skin rashes, itchiness and sore eyes, ears or nose.

Although the forested area around the lake is also a favorite destination for deer and black bear hunting, by and large Mattamuskeet is renowned for its waterfowl hunting, as well as unique birdwatching opportunities.

Campbell said that the recent government shutdown limited the refuge’s annual aerial survey of waterfowl, but it is evident that plenty are visiting.

“They’re still coming,” he said. “They’re taking advantage of our impoundments.”

But the water quality effects on wildlife are a concern of the refuge, he said.

“There’s never an instantaneous change when it comes to waterfowl,” Campbell said. “We’ll keep monitoring.”

The cyanobacteria issue is the latest symptom of the precipitous decline in Lake Mattamuskeet’s water quality.

Serious problems have been evident for at least 20 years, when the submerged aquatic vegetation, or SAV, on the lake’s west side started dying off, resulting in spiraling ecological consequences.

Turbidity increased and clarity decreased, hindering sunlight reaching new growth of SAV, which soon disappeared altogether. Without SAV to consume nutrients draining into the lake, pH levels and chlorophyll increased and phytoplankton became dominant. Surveys taken in 2017 on the east side of the lake found zero SAV.

In 2016, the Environmental Protection Agency added Mattamuskeet to its state list of impaired waterways.

Lake Mattamuskeet, situated on the Hyde County mainland, is 6 miles wide, 18 miles long and typically averages about 2 feet in depth.

Surrounded by farms and timberland, the 40,000-acre lake is famous for attracting hundreds of thousands of migratory waterfowl every year, most notably the tundra swans in the winter.

But with no SAV – an important food source – the birds are mostly bypassing the lake for nearby private and refuge impoundments, which are intentionally flooded agricultural lands or moist soil areas with native plants created to attract waterfowl. The graceful white swans also still visit the lake for sanctuary.

Much of the nutrient-rich water from both the farmlands and impoundments drains into the Mattamuskeet. In addition to intricate drainage canals to and from the lake, the lake itself depends on water control systems to balance water levels.

But increased rainfall in recent years has created enormous challenges to all the drainage, and exacerbated Mattamuskeet’s already substantial problem with water quality, Campbell said. With deeper water, even less light can reach the lake bottom, hindering recovery of the SAVs, and blocking the passive operation of the water control gates.

“The lake had been unable to flush through our gate system,” Campbell said.

The gates don’t open as frequently because the water pressure is higher on the sound side of the canal. So, what you have is the same amount of water … and less water being able to leave the lake.”

Scientists have been monitoring and studying the lake intently since at least 2012, and it became evident that the lake required a comprehensive approach in order to recover its SAV, the best indicator of a healthy waterway.

In 2017, the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Hyde County established a partnership and hired the North Carolina Coastal Federation to develop a restoration plan.

After 18 months working with an 11-member, community-based stakeholders group, the federation and the partnership submitted Dec. 7, 2018, the final draft of the Lake Mattamuskeet Watershed Restoration Plan to North Carolina Division of Water Resources for review.

Although its contract work is completed, the federation is continuing to assist in the restoration efforts, said Michael Flynn, the group’s northeast coastal advocate.

“The plan has been a priority of the Coastal Federation,” he said.

Ongoing or planned research includes restoration of the SAV; the effects of impoundments on water quality; control of invasive carp; and active watershed drainage and management.

“The No. 1 problem is excessive nutrients in the lake, which contribute to algal blooms,” said Wendy Stanton, refuge biologist at Mattamuskeet.

Two toxins – cylindrospermopsin and anabaena – have been detected in the cyanobacteria present at Mattamuskeet, Stanton said.

But she stressed that no one is pointing fingers.

“The lake is what it is,” she said. “It took a long time to get that way, and it’s going to take years and years to restore it. It’s a long-term process.”

In addition to numerous research efforts being conducted by academic, government and nonprofit environmental organization scientists, there are also programs available to private landowners to help implement best management practices to improve water quality and enhance wildlife habitat.

A priority in the management plan is to develop a drainage association to continue to move forward with the needs of the community, Stanton said. Another possibility under consideration is creating another outflow canal to the north of the lake.

“The bottom line is we have got to improve the water quality in that lake,” Stanton said. “One thing that’s so refreshing and so amazing is how everyone came together. Everyone wants the lake to be healthy.”