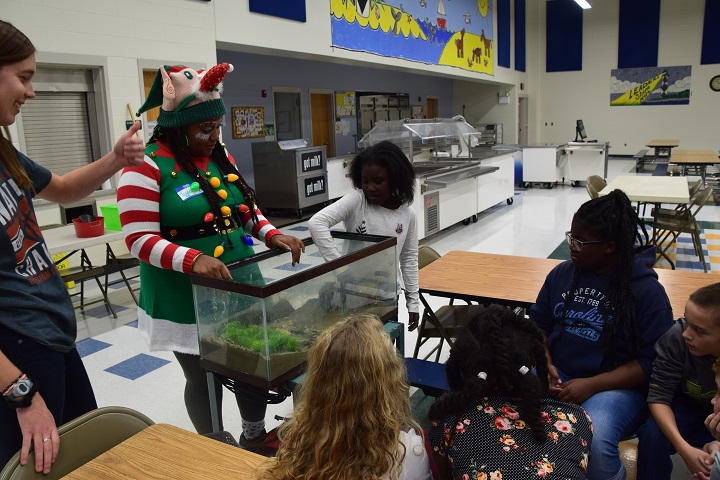

BEAUFORT – Two Duke University Marine Lab undergraduates stood last month behind an aquarium, facing about a dozen kindergarten through fifth-graders, all members of the Boys and Girls Clubs of the Coastal Plain, seated at tables in the elementary school cafeteria, where the Beaufort Elementary Unit is based.

Serving as a wave tank, the average-sized aquarium had a few inches of sand sloping across the bottom, mostly covered in water. A brick was on the thicker side, meant to mimic a hardened shoreline, parallel to a wooden block slightly submerged in the water, which was used to make the waves.

Supporter Spotlight

Barbara Lynn Weaver, a junior majoring in plant biology, told the club members that the brick represents a hardened shoreline, which could also be made of concrete or wood, and that people put these in their yards where the water meets the land because they want to keep their soil dry and keep it from eroding.

Taylor Walker, a senior majoring in marine science, said, “We’re going to make some waves and we’re going to see what happens when you have water going against something hard,” as she lifted the rectangular piece of wood to make waves that lapped against the brick.

Walker and Weaver were at the elementary school, to demonstrate a hands-on science, technology, engineering and mathematics, or STEM, project, along with fellow classmates Isabel Harrington, a junior majoring in environmental studies, and Haven Parker, a senior studying environmental science and policy, who were leading the arts component of the project.

As part of their Conservation Biology and Service Learning class, the Duke students designed the project to help kindergarten to seventh-grade students learn about the science behind storm surge and express their hurricane experiences. The undergraduate students also engaged with students at Beaufort Middle School Nov. 30 and visitors to the Dec. 1 Waterfowl Weekend at Core Sound Heritage Center and Waterfowl Museum on Harkers Island.

Weaver told the Boys and Girls Club members at the elementary school that when there are big waves, the energy has to go somewhere.

Supporter Spotlight

“So if it’s going to hit a wall, where is that water going to go?” she asked the kids, explaining that the wave will either go straight up, which causes splashing, or the energy will cause the waves to go over the wall and wet the dry ground.

“Taylor and I have another kind of shoreline that we really like, called a living shoreline, which you guys are going to get to help us build,” said Weaver, adding that a living shoreline is made out of two things, oysters and marsh grass.

The brick was removed and the students helped “plant” marsh grass, which was actually just plastic aquarium grass, and oysters, or more specifically, oyster shells. Weaver told the group that oysters are bivalves, like clams and mussels.

“The funnest fact I could possibly give you,” Weaver began, is that bivalves eat by sucking water in, instead of biting things like sharks do. “And instead of chewing it like we do, they spit it back out, but instead of spitting it back out of their mouths, bivalves suck all that water in, and poop out anything they don’t want to eat … but that means they’re pooping out soil. That’s kind of funny, but if you have a live oyster that’s cleaning the water, it’s sucking that water in and pooping soil out.”

Julia, a fourth-grader, stepped up to the aquarium and demonstrated how the living shoreline worked.

“Pay close attention to what’s happening in this upper beach, you may see it might get a little wet but overall the grass is staying in place, the oysters are staying in place, and the water isn’t splashing up like it was before,” Walker said.

Oysters and plants slow the waves down. “The thing is, you can’t stop a wave from coming. If there’s really big hurricane wave, it’s going to be powerful enough to go over the wall, like we saw before, but you can slow it down, and you can slow it down using the plants,” Weaver said.

Walker added that some of the fish and crabs we eat lay their babies on living shorelines and then they grow up so that we can eat them “It’s very important to have this around instead of a brick wall where no organisms like to live.”

Harrington and Parker were nearby working with a different group of club members who were exploring through art their experiences during Hurricane Florence.

The students used a range of paper colors meant to represent the different temperatures for a Hurricane Florence heat map mural. The outer colors of blues, greens and purples represent cooler temperatures while the inner temperatures are hot colors – red and yellow, Parker said.

As the groups were wrapping up their activities, club member Julia said she learned during the activity about living shorelines and that oysters clean the water and the marsh grass helps the grass stay.

Third-grader, Kendra, who drew “Go Away Florence” as her art project, added that she learned about oysters and that the living shoreline will help the environment because it will help clean the ocean and help get the trash out.

Harrington told Coastal Review Online before the club members filed into the cafeteria before the service project began that they ask the students two different prompts: What would you say to the hurricane? What would you say to the community to give them hope? and encourage them to draw or write their answer.

Harrington, a Bucknell University student who attended Duke for the semester, said most tell the hurricane to “go away” and are concerned about WiFi, or losing their internet connection. “But a lot of the kids are hopeful, have a happy joyful spin on it.”

Parker said that with the two groups they worked with previously on the Hurricane Florence heat map mural, she noticed the kids often bring up pets when asked about their experience. “I think they find it easier to talk about their pretty traumatic experience with the hurricane by anthropomorphizing their pets. … We ask them about their pets and ease into asking about their experience.”

Harrington explained that the point of the activity is to help kids be able to talk about the hurricane, for psychological and long-term effects, “Because there’s a lot after the fact, we wanted to give them a lighthearted outlet to have that experience to reflect on the hurricane, normalize it, reflect and move on.”

While at Beaufort Middle School they worked with sixth- and seventh-grade students, Weaver said, explaining that the project presentations at the middle school went well. The students were really interested in living shorelines and how they can use them in their own backyards, “and they were telling us they were going to show their parents, which is really fun.”

Walker said that the following day at the waterfowl museum about a dozen middle school students found them and brought their parents.

“We let the kids show the parents how the wave machine worked, not only did they get to teach their parents something, but they all got that experience together,” Weaver added.

The parents had personal stories, Walker added, telling her that they knew of someone that their hardened shoreline was damaged or they were working on repairing one.

The project began this year as part of the marine lab’s undergraduate course in conservation biology and service learning under Liz DeMattia, a research scientist leading the Community Science Initiative.

The course introduced university students to conservation biology and explored service learning as a way to make positive change, DeMattia explained. While the project was part of the undergraduate course that took place in the fall, Duke Marine Lab offers many STEM learning opportunities year-round, including marine debris programs, water quality programs and summer programs.

“Given the devastating effects of Hurricane Florence to our Carteret community, the conservation biology class focused their service learning projects on using art, creative writing and scientific discovery as a means to express individual hurricane experiences,” she said.

She said that the reaction of participants and students has been “incredibly positive.”

“This program connected Duke undergrads to kids in our community. Our young K-12 kids benefit by interacting with college students and exploring STEM together,” DeMattia said, adding that the Duke undergrads benefited by being active in the community. “Both the Duke undergrads and the K-12 students benefited by sharing their Hurricane Florence experiences with each other, and working together to create art that shows how resilient our community is.”

DeMattia added, “We currently are dealing with many environmental issues in our communities — from flooding and storms, to water quality and health. Solutions to these issues, and others, will come from individuals who understand STEM and can apply their knowledge to help our communities deal with our environmental issues.”

Ava Bryant, Boys and Girls Clubs of the Coastal Plain unit director at Beaufort Elementary School, and leader Talley Long in a follow-up email explained that STEM activities are hands-on, minds-on, which aim to increase student interest in math and science, and are usually relatable as well.

“The hurricane activity that the Duke undergrad students did with our Boys and Girls club members was significant and relevant. Through the use of a wave tank, students learned about hurricane-force waves and its impact on the environment,” they wrote. “The tank modeled the significance of our marshes and how they protect against storm surge. The tank also modeled oysters and how they are able to stay in place.”

When the students drew their Hurricane Florence experiences, one student drew a house near a dock with waves approaching, another drew a scene of marsh grasses flowing under storm surge, and yet another student drew a sign that simply stated, “Go Away Hurricane Florence.”

“We hope that students will appreciate this area in which they live, and as they grow older, and become more involved in this community, will have a desire to protect their environment, specifically the marshes,” the email said. “We also appreciate the value of having young adults, such as the undergrad students, be involved in modeling positive behavior for our club members.”