HYDE COUNTY – On a June day more than 10 years ago, a lightning strike ignited a fire on private land adjacent to Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge. Dried crisp by drainage and drought, the deep layer of peat under the farm fields soon began to burn, turning the once-boggy pocosin land into smoldering coals.

The Evans Road fire, not officially declared out for seven months, cost $19 million to manage and consumed 41,060 acres in three counties, spewing plumes of choking, carbon-rich smoke into the air for miles. But now scientists want to return tons of carbon to where it had once been safely stored: in the peat soil of that same Hyde County land.

Supporter Spotlight

Following years of research on pocosin, Duke University last month announced the launch of an innovative “carbon farm” project on 10,000 acres that could potentially capture and store tons of carbon dioxide in the thick mats of decomposed plant deposits. Once it’s fully operational, it would be the largest carbon farm in the United States.

Carbon farming involves management of agricultural land with practices that promote storage of carbon in the soil to keep it from being released into the atmosphere.

That stubborn wildfire in northeastern North Carolina in 2008, which smoldered 3 to 5 feet in the ground, illustrates why pocosin has received new attention in climate science: Its organic peat soils can absorb and hold extraordinary amounts of CO2, the greenhouse gas emitted from burning fossil fuels that is most to blame for global warming.

It is no small irony that another enormous source of carbon emissions is smoke from peat fires, but even dried out peat releases some carbon.

The two-year pilot project, conducted in an agreement with private owner Hyde County Partners LLC, involves re-wetting the peat and restoring the natural pocosin wetlands, which had been ditched and drained years ago for agricultural use, said Curtis J. Richardson, director of the Duke University Wetland Center. In the process, he said, the naturally spongy pocosin – Algonquin for “swamp on a hill” – would be expected to regain its exceptional ability to trap and hold carbon in the peat soil, as well as its resistance to wildfires.

Supporter Spotlight

“The landowner wants to make this into a model system for carbon farms, for wildlife, for biodiversity,” Richardson told Coastal Review Online, noting that the owner wants to remain anonymous. “He’s going to use this land to restore a piece of the natural system.”

If the initial restoration work on a 300-acre section proves successful, which would involve measuring and verifying the amount of carbon the land can store, the university has rights for up to 20 years to use the entire 10,000 acres to generate carbon credits. The goal is to offset the university’s carbon emissions and help it obtain carbon neutrality by 2024. Any additional credits could be sold to others.

Carbon markets, most notably in California, compensate participants with credits for keeping carbon emissions out of the environment.

“We have rights to do the research to determine the best way to restore the land,” Richardson said. “The funds would go back, of course, to the private landowners and the party that buys them would get the credit.”

“The landowner wants to make this into a model system for carbon farms, for wildlife, for biodiversity.”

Curtis J. Richardson, Director, Duke University Wetland Center

Pocosin’s waterlogged peat is naturally anaerobic and contains antimicrobial compounds that hinder decay, allowing the carbon to stay put in the peat for millennia, if undisturbed. Peatlands known to science cover about 3 percent of the Earth’s land surface, but store more than twice as much carbon as the entirety of the planet’s forests.

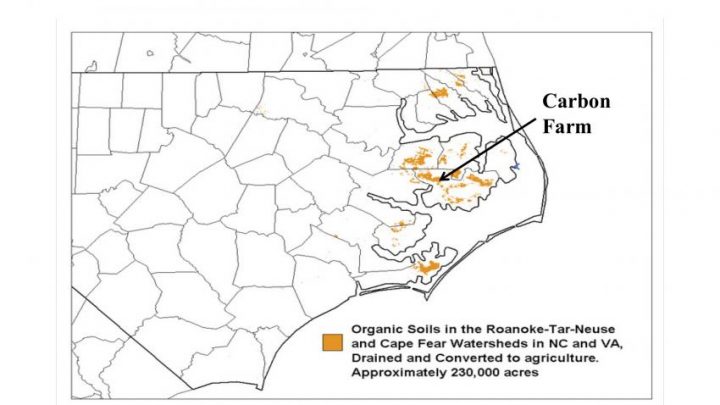

North Carolina has a large amount of peatlands.

“They probably have some of the best in the United States,” Richardson said. Left untouched, the pocosin captures carbon, but when it’s drained and ditched for farmland, the carbon is oxidized.

“They’re sort of the perfect model for sequestering carbon,” he said.

The unique quality of peatlands comes from dead vegetation sinking into watery landscapes, depriving the material of air needed to rot. As a consequence, the organic material accumulated and compressed over the centuries, trapping carbon remaining in the once-living plants. In a few more centuries, the material could become coal.

Pocosin is technically shrub-dominated peat wetlands.

There are about 2 million acres of pocosin in the state, with about one-third to 50 percent of it now under federal control and protected, Richardson said. But a lot of it is farmland, he said, some of which is not doing well because of saltwater intrusion.

According to a Dec. 11 press release from Duke, carbon farming programs in Australia, New Zealand, Europe, Canada, California and the Midwestern U.S. have shown that 2.5 acres of land can store more than a metric ton of carbon annually. But a five-year study Richardson conducted on the Pocosin refuge, the statement said, found that pocosin in its natural state can potentially store 10 to 15 times more metric tons of carbon per year than drained or unrestored agricultural lands – some of the highest net carbon credit values ever recorded.

Hydrology restoration and re-wetting work has recently been completed on three ditched areas in Pocosin Lakes, refuge totaling about 35,000 acres, said refuge manager Howard Phillips. The rest of the refuge, situated at the headwaters of the Alligator River, was less affected by drainage measures. Still, a water management plan is being developed for the entire 110,106-acre refuge, he said.

“We’re moving into a management/maintenance stage,” he said in an interview. “We’ve adjusted the drainage level to maintain moisture in the soil.”

Although neighboring farmers had blamed the restoration work for flooding of their land, Phillips said that it appears over time the landowners have accepted that problems were mostly caused by excessive rainfall. The refuge, he added, is continuing to work with The Nature Conservancy on redesign of its weir systems to slow down drainage.

Phillips said he welcomes the Duke project, which is being done on land that abuts the refuge.

“We get wetlands restoration out of those private areas,” he said. “That’s a big chunk of land right there that’s been ditched and drained.

“It would be great to see that restored. That land sitting right there is a potential source of fire. In a drained state, it has a higher likelihood of catching on fire.”

Restoration on the refuge’s Clayton Blocks, 1,241 acres on its southwest side, was completed in March 2017 with the assistance of the The Nature Conservancy, according to a summary provided in an email from Eric Soderholm, Albemarle-Pamlico restoration specialist at the nonprofit’s office at Nags Head Woods.

The re-wetting process included construction of a new berm and installation of new structures to control water levels in canals. The project conformed to the American Carbon Registry’s new Restoration of Pocosin Wetlands methodology, which was developed with assistance from the U.S. Geological Survey’s LandCarbon team, East Carolina University and Duke University Wetland Center.

“If fact,” Soderholm said, “the restoration area served as the proof-of-concept site for development of this newly approved methodology in partnership with The Nature Conservancy and TerraCarbon LLC.”

Subsequent measurements at the Clayton Blocks and other restored pocosin sites estimated that emission reductions are expected to be 5,500 to 8,000 metric tons of CO2 per year.

In order to qualify for carbon credits, the project’s emission reductions must be documented and quantified. An independent Carbon Registry validation process is currently underway, working with details provided in the Greenhouse Gas Project Plan developed jointly by the Conservancy and TerraCarbon, an Illinois-based firm that advises on development and sale of carbon offsets.

Ultimately, the intention is to develop a protocol that would allow private landowners to sell carbon credits, providing a new source of income to them while fostering environmental benefits such as decreased saltwater intrusion and improved wildlife habitat.

“What you’re seeing now is the realization from folks, whether from business or government, to act now on climate change.”

Brian Boutin, The Nature Conservancy

Brian Boutin, director of the Conservancy’s Albemarle-Pamlico program, said that once the credits are authorized and the project is compensated, the Conservancy would be able to aggregate other projects under the umbrella of the Clayton Blocks project.

Boutin said that even without a federal mandate to create a carbon market – California currently has the only big market – large corporations are seeking to offset their carbon footprint.

“What you’re seeing now is the realization from folks, whether from business or government, to act now on climate change,” he said.

Richardson said he is not certain how many carbon credits the restored Hyde land could garner, but indications from tests at the nearby refuge site show that Duke University’s 258,000 metric tons of carbon emission in 2017 could be quickly offset, with thousands more tons of credits remaining to sell. Once it’s fully operational, it would be the largest carbon farm in the United States.

“I really hope it works well because it could be good for the local community and for the state,” he said, “and keep carbon in the ground.”