Many a beach-going visitor to the Outer Banks has no clue that a rare maritime forest straddles the west side of Nags Head and Kill Devil Hills. But even locals may not know that Nags Head Woods was home to a vibrant community for close to a century.

All that remains today are four family cemeteries, and on a ridge far above Roanoke Sound, footings of long-gone buildings.

Supporter Spotlight

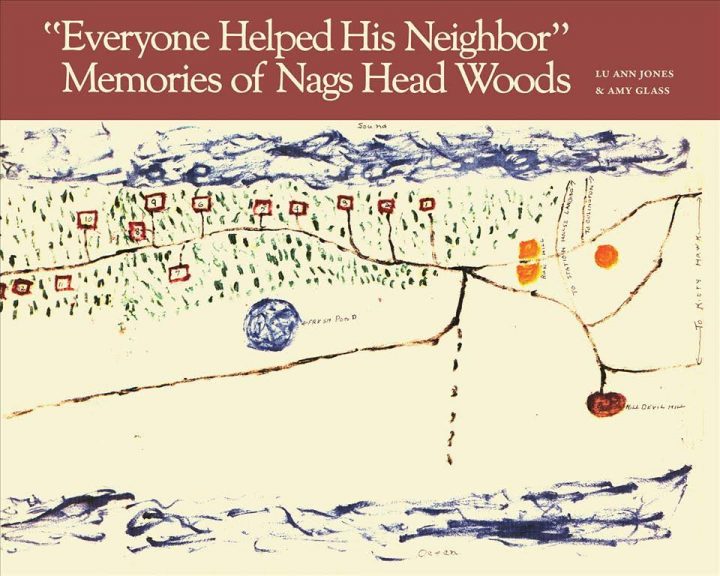

But now there is also a newly reissued book “‘Everyone Helped His Neighbor’: Memories of Nags Head Woods,” by Lu Ann Jones and Amy Glass, that restores the history of the tight-knit community to its rightful place in the Outer Banks zeitgeist, told through interviews in the late 1980s with elder folks who grew up under the trees.

“What a privilege it was to do the local history interviews,” Jones told a small audience at a recent discussion and book signing in Nags Head. “I don’t think we knew we were breaking that kind of ground, but we’re very proud to share those voices.”

First published in 1987 by The Nature Conservancy, the nonprofit owner of 1,200-acre Nags Head Woods Preserve, the book, which was re-released in July, includes a new forward and afterword by the authors, as well as a few minor corrections, but otherwise it is the same.

“Amy and I always thought this book had life,” Jones said. “And indeed it does.”

Of the 60 or so people who attended the event, about 40 were descendants of the Nags Head Woods community, Jennifer Gilbreath, Nature Conservancy conservation coordinator and organizer of the event, said in an interview.

Supporter Spotlight

“‘Everyone Helped His Neighbor’” was out of print for some time, although it is uncertain for how long, or how many had been originally printed, she said.

“I think it was really important that this project gave Outer Banks people from Nags Head Woods the opportunity to tell their story.”

Lu Ann Jones

Gilbreath said that a phone call last year from Kill Devil Hills town clerk Mary Quidley asking if the preserve had a copy of the 1987 book had first sparked her curiosity.

As it turned out, the conservancy had no copy, she said, and nor did anyone else.

“I found one on eBay for $50,” Gilbreath said. “It was the only one I could find.”

Intrigued, she kept following the publishing crumbs, and eventually found support from the University of North Carolina Scholarly Press to pursue a new printing. Once she tracked down Jones and Glass, who had remained friends, there was no going back.

As part of the Southern Oral History Program at University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, Jones and Glass had spent about two intense weeks in 1986 doing in-person interviews with about 10 surviving members of the Woods community, which had once numbered 40 families.

In between the narrative history of the Outer Banks and Nags Head Woods, the 67-page book stitches together historic photographs and long paragraphs of memories and anecdotes quoted from the interviews. By using the interviewees’ own voice, the book chronicles the daily routines of their lives, told in surprisingly vivid detail.

In one example, Evelyn Wise Gray recalled how she caught crabs as a teenager to peddle to “summer people” for good money:

“I’d get up mornings before day, and go lay down on a hill waiting for the soft crabs to come, because I wanted to be the first up … I’d just grab ‘em; I could never do nothing with a dip net. Sneak up on ’em and feel ’em out with my toe and pick ’em up. . . And in the afternoon when I caught all my crabs and got ’em shedded, well, I’d pack ’em in wet grass and go along, ‘Wanna buy some crabs?’ to every house.”

“I think it was really important that this project gave Outer Banks people from Nags Head Woods the opportunity to tell their story,” Jones said in a telephone interview.

Most of the people the young women had spoken with were then in their 60s, with some as old as age 93, and had left the woods in their teen or young adult years. Most interviews were done at the subject’s home and lasted about an hour and a half, although one woman chose to communicate through letters. Each interview was recorded and later transcribed.

When a few clips from interviews were played at the event, the thick Outer Banks brogue of the people speaking sounded as long gone as the days they were reminiscing about.

“I think the stories of the narrators stayed with me for a long time,” said Jones, who is employed as a National Park Service historian. “The people we talked to remain very much alive to us through those stories.”

It was a revelation from the interviews, Jones said, to learn that people from Nags Head Woods, and by extension, the Outer Banks, were quite mobile and interconnected, even “cosmopolitan.”

“These people were not isolated,” she said. “In a maritime world, you can go lots of places in a boat.”

Before World War I, the community in Nags Head Woods was vibrant and thriving. At its height, according to the Conservancy website, it had “13 homesites, two churches, a school, a store, farms, a gristmill, and a shingle factory.”

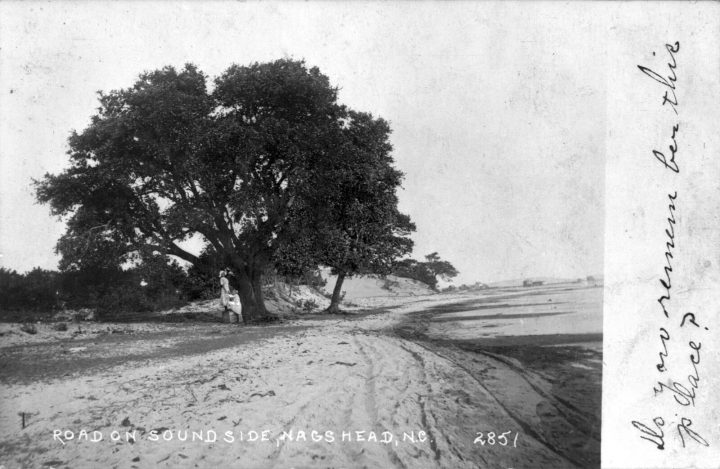

In what could be considered a precursor to the modern Outer Banks’ economy, the Nags Head Wood community was in part an outgrowth of serving the nascent tourism business, “summer people” who started coming in the 1830s to the sound side south of Jockey’s Ridge. History is fuzzy as to when people settled down in the woods, but some of the headstones in the Baum cemetery record deaths in the 1860s.

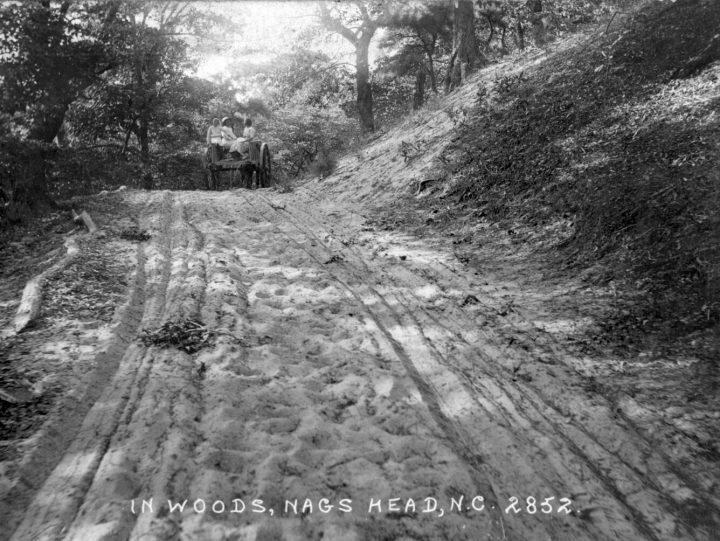

Compared with the open exposure to the coastal elements of much of the barrier islands, the maritime forest was sheltered by large dunes: Jockey’s Ridge on its south and Run Hill on the north. Most houses were built from timber cut down in the woods or salvaged from shipwrecks, high on a ridge away from the risks of surf and tide.

Men made a living farming and fishing. Women cleaned, cooked and peddled crabs, helped by children who were also expected to do their share of work.

Residents raised chickens, hogs and cows – it was open range until 1937 – gathered nuts, hunted, picked figs and berries, grew gardens, spun yarn, made curtains. For fun, they shared a big Sunday dinner after church, visited with friends and family and built bonfires on the beach.

“For me, this really encapsulates a moment in time, where I was very much embedded in the community.” Glass said, adding that she was impressed by the descriptions of “really back-breaking work” done by both men and women – “all the hauling, all the moving from the ocean side to the sound side.”

The people who were interviewed had grown up on the Outer Banks when the few motor vehicles on the islands traveled on sand roads and nearly everything they had – their buildings, their clothing, their food, their boats – was made or provided by their family or someone in their community. Horses, boats and walking were the means of transportation.

“They were scrappy people,” she said. “They used their resources well.”

But with the two World Wars, change came quickly. Many men left to join the military or work at the shipyards. By the time the last of the Nags Head Woods community moved away in the 1950s, people were traveling everywhere by motor vehicles and airplane and the Outer Banks was at the cusp of an explosion in tourism and development.

Glass, who works in the technical design field, fondly recalled her conversations with the older folks who grew up at such a unique place and time.

“Oh, it was fun,” she said. “The generosity of those narrators – to be willing to spend time with virtual strangers and really tell us in great details their stories, their family histories, and to patiently answer our questions – it’s really a gift to hear from that generation, particularly now because they’re no longer living. “

Compared with today’s distracted culture, Glass said, those folks in Nags Head Woods seemed to have shared more of life’s difficulties and pleasures with their friends and neighbors.

“They were proud of how they lived,” Glass said. “They lived simple lives, as they said, ‘but we were happy.’ That theme really comes through in the book.”