Reprinted from North Carolina Health News

Sean O’Gorman learned firsthand this spring how rip currents can transform fun in the surf into a lethal hazard at a North Carolina beach.

Supporter Spotlight

Last April, the upstate New York firefighter was relaxing with family at an Emerald Isle beach when two teenage sisters in the water started yelling for help. A rip current had pulled them offshore.

Trained just weeks before in swift-water rescue techniques, the Oswego Fire Department member swam through choppy waves to the girls, hooked their boogie boards to his feet, and towed them to safety.

“It was a nice thing to be in the right place at the right time,” O’Gorman said.

Not everyone is so lucky.

About 100 people drown in rip currents each year nationally, according to the U.S. Lifesaving Association. In contrast, just an estimated five people worldwide died from shark attacks last year.

Supporter Spotlight

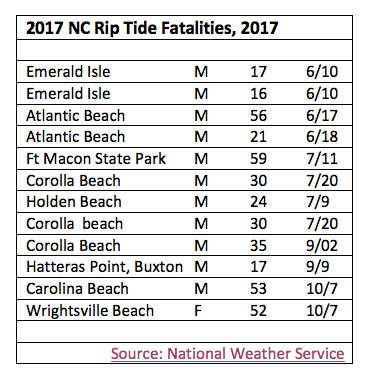

Only California and Florida reported more rip current drownings than did North Carolina between 1999 and 2013, according to National Weather Service data. Rip currents were blamed for 12 deaths at beaches here in 2017.

Frightened and struggling swimmers require rescuing from rip currents frequently along this state’s coast, sometimes by untrained individuals putting their lives at risk. Dozens of rescues were tallied at North Carolina beaches in just the first week of July.

Researchers, lifeguards, coastal town governments, even rental property managers, have tried to educate beachgoers about this peril for years.

“Many of the tourist offices will have brochures available, so do the rental companies. But if you are on your way to beach you are not going to pick up a brochure and read it,” said Spencer Rogers, a rip tide and coastal erosion specialist with the North Carolina Sea Grant program.

So communities frequently post warning signs along public accesses to a beach. Nonetheless, many people remain unaware.

Natural Hazards

Rip currents form nearly every day along North Carolina’s 170-plus miles of barrier islands, Rogers said.

“On most days no one would notice,” he said, because only a fraction are powerful enough to push swimmers away from the shore.

Incoming waves often build the currents by depositing water between sandbars and the shoreline. In time, portions of those sandbars collapse and water rushes through the resulting gaps, away from the beach.

These ephemeral current channels can be as narrow as 10 or 20 feet or much wider. They can be strongest when waves hitting the shoreline are higher and more frequent than average, say after a storm passes by offshore.

“A big part of the trouble is that they don’t always look like trouble,” Rogers said. Water within these currents can appear calmer than water to either side.

“The waves can look milder and smaller because they are not breaking on the sandbar,” Rogers said. “That gives the exact wrong message to beach users. That’s where they want to put down beach blankets.”

Knowledge is Safety

Many North Carolina organizations have worked for years to educate people about this danger at our beaches.

“You name it and we’ll print a rip current warning on it,” Rogers said, including lifeguard stands, auto bumpers, frisbees, rental house refrigerators and garbage cans.

The Hatteras Island Rescue Squad, for one, holds weekly information sessions on risks from rip currents and other shoreline hazards every Monday into August. The National Weather Service produces rip current forecasts for shoreline in North Carolina and other state.

Not everyone is at equal risk of harm. “The drowning and death statistics show a much higher risks for younger males, 16 to 30,” Rogers said. “Inexperience is not always involved. It’s surprising the number of stronger swimmers who get in trouble.”People who understand these currents advise beachgoers to swim only when lifeguards are present. They also urge people to swim with flotation devices, like the boogie boards used by the teenage sisters O’Gorman rescued.

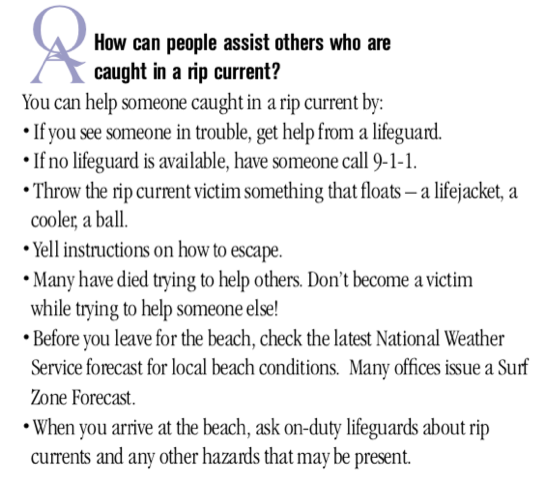

Rip currents can be dangerous to people out of the water too. “About 25 percent of North Carolina deaths in last few years have been better swimmers attempting rescues. Someone sees a child or a friend or even a stranger and they attempt to rescue them,” Rogers said.

Tossing a flotation device toward someone in distress after someone has called 911 is a safer alternative, he said.

O’Gorman, the firefighter who muscled in the teenagers at Emerald Isle, agreed that not everyone should attempt what he did.

Because he had very recently had the right training, he knew he had the skill and the physical stamina to help.

Before he tried, he approached the teenagers’ distraught family. They told him they had called 911, which was just right. Given how frightened the girls were, however, he went in.

“You have to assess your own ability,” he said.

And that assessment needs to be right.

Learn More

This story is provided courtesy of N.C. Health News, a website covering health and environmental news in North Carolina. Coastal Review Online is partnering with N.C. Health News to provide readers with more environmental and lifestyle stories of interest about our coast.