First of two parts

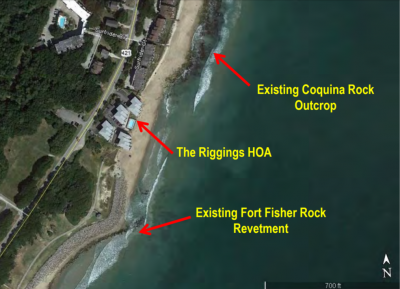

If you watch the tide go out near the south end of Kure Beach, where the town ends and the man-made rock revetment at the Fort Fisher State Historic Site begins, you’ll see emerging an irregular assemblage of well-worn coquina rock.

Supporter Spotlight

At low tide, the sedimentary rock outcropping stretches along the coastline in uneven clusters in various degrees of exposure, parts of it sunbaked and dry, other parts green with algae. On just about any day, beachgoers are drawn to them, looking for what’s hidden in the well-worn bowls and crevasses.

Although it is not unusual to see large rocks here and there along the North Carolina coast, this rock structure is naturally occurring and, because of that, incredibly rare.

Kure Beach’s intertidal coquina rock outcropping is the only natural marine rock exposure on North Carolina’s beach system and one of only a handful of such places along the Southeastern coast. Composed of shell fragments, sediments and fossils cemented together with calcite, it was formed in the late Pleistocene Epoch, or ice age, according the 1982 agreement designating it a Natural Heritage Area.

“The potholes, cracks, and abrasions bowl of the coquina exposed during low tide offer prime habitat for various species of marine algae, sessile animals, and other forms of marine life,” the document states. The outcropping’s value, it says, is both as an educational resource and an important habitat for fish and invertebrates. But decades ago, it served another purpose.

County commissioners back in the 1920s gave a contractor permission to remove from “a considerable length of the beach” a 50- to 100-foot-wide strip of coquina rock, or about 6,000 cubic yards, to use in building a local section of U.S. 421, according to a history of the Army Corps of Engineers’ Wilmington district.

Supporter Spotlight

“The excavation of the coquina coincided with the reversal in the erosion cycle that occurred around 1926,” according to the document. “The board offered no definite conclusion concerning the role the coquina removal played in the erosion of the fort, saying only that ‘It is conceivable that this, by reducing the quantity of resistant material at a critical point, has accelerated the erosion.’”

This year, in addition to its twice daily tide-driven exposure on the coast, the intertidal marine outcropping that remains at Fort Fisher also emerged much farther west in Raleigh during the windup of this year’s short session of the General Assembly. It was included as a description in a provision aimed at loosening sandbag rules that was written so tightly it could only be one place.

The provision was part of a multi-section regulatory bill passed in late June amid a flurry of legislation in the last week of the session. It amends state statues on temporary erosion-control structures, giving the state’s Coastal Resources Commission new authority to “repair or replace” a sandbag wall under certain conditions, specifically that it had to have been permitted prior to July 1, 1995, and it had to be adjacent to an intertidal marine outcropping designated a State Natural Heritage Area. As stated above, there is only one such location.

For the homeowners and investors at The Riggings, a four-building, 48-unit condominium complex hugging the shoreline just in front of the coquina rocks, the provision means a potential solution to one of the longest-running battles over sandbag walls and with it, the salvation of a set of structures threatened with destruction almost since they were built in 1985.

Candice Young, president of The Riggings Homeowners Inc., said in an email response to Coastal Review Online that there is finally hope that some solution can finally be reached.

“All the Riggings ever wanted was to be able to protect our homes, foundations and property legally,” she said. “We are hoping that after many years of contentious exchanges that we can finally exhale.”

New Chapter, Old Story

The story of The Riggings’ erosion problems started not long after the development was built in 1985. Coastal storms quickly threatened to undermine the new development and a sandbag wall was erected under an agreement with the town.

When the jurisdiction of temporary erosion-control structures moved in the 1990s from local governments to the state’s Division of Coastal Management and the Coastal Resources Commission, the wall at The Riggings was expanded. It became even more critical after a series of active hurricane seasons in the late 1990s further eroded the beach.

Under state law, hardened structures are generally not permitted on the North Carolina coast. Sandbag walls, which cause erosion problems when left in place permanently, are supposed to be temporary and must be removed after two or five years, depending on the structure’s size.

Like many hot spots along the coast, the sandbags at The Riggings were allowed to stay in place through a series of variances granted through the commission. The extensions bought The Riggings time, but no permanent solution.

In 1995, the situation got worse after the existing revetment protecting Fort Fisher, built before the hardened structure ban, was expanded. The state granted an exception to protect the fort because of its historical significance. The expanded rock wall added to the disruption of the flow of sand to the beach in front of The Riggings.

Also, in the mid-1990s attempts to add The Riggings area to the federal beach re-nourishment plans approved for Carolina Beach and Kure Beach were dealt a blow when the Army Corps of Engineers rejected the idea citing policy that would not allow them to approve a plan that covered the Natural Heritage Area. Re-nourishment of the beach begins to taper off roughly 1,500 feet north of the coquina rocks and ends about 600 feet north and The Riggings.

Pre-disaster Plan

With few options left in the early 2000s, Kure Beach, under then-mayor, the late Betty Medlin, worked with then-Rep. Mike McIntyre, D-N.C., to secure a Federal Emergency Management Agency pre-disaster grant to cover most of the cost of relocating The Riggings. Under the plan, the town would buy the oceanfront area, the existing buildings would be demolished and a new complex built on a parking lot already owned by The Riggings on the other side of U.S. 421.

In 2004, the town was awarded a $2.7 million FEMA grant to purchase the oceanfront property. The rest of the cost of the $3.6 million project, roughly $904,000, was to be covered by property owners. But the project, which required unanimous consent of the owners, was voted down by The Riggings homeowners association partly over the cost, about $125,000 per unit, as well as potential difficulties for some property owners to get approval from mortgage holders. Concerns were also raised about access and use of the oceanfront property once it was taken over by the town.

On May 1, 2007, The Riggings HOA informed Kure Beach officials of the association’s vote and that its members had opted to decline the federal grant.

Soon after receiving official notice from the town that the FEMA grant had been terminated, the state’s Division of Coastal Management notified the association that under the terms of the variance approved to give The Riggings time to work on the relocation project, the refusal of the grant meant the sandbag wall would have to come down. Homeowners lost a subsequent appeal to the Coastal Resources Commission and took the case to court.

In August 2007, the division sent The Riggings notice of violation over the sandbag wall. A second notice was sent a month later.

The Riggings filed an appeal to the Coastal Resources Commission asking for time to work on an alternative beach re-nourishment plan. In early 2008, the commission reviewed The Riggings’ appeal and denied a new variance and the HOA filed for judicial review in New Hanover Superior Court.

In 2012, the trial court ruled that the commission had erred in its ruling. The state appealed the ruling and The Riggings HOA filed a cross-appeal.

In August 2013, a three-member panel of the state Court of Appeals agreed with the trial court in a 2-1 decision, finding that The Riggings’ “substantial private property interest outweighs the competing public interests” considered by the commission.

“With a rock revetment to the south, and depleted coquina formations to the north, The Riggings truly is caught between a rock and a hard place,” the majority wrote. “In this scenario, we must balance The Riggings’ private property interest with competing public interests to determine whether a variance is consistent with the “spirit, purpose, and intent” of CAMA’s framework. Without a variance, The Riggings’ condos will likely be destroyed by erosion. We believe this private property interest outweighs competing public interests.”

The ruling sent the request for a variance back to the commission, which then granted a variance in December 2015 to allow the sandbags to remain in place while the HOA studied alternatives.

Since then, HOA officials have been required to update the commission yearly on the status of the sandbag wall as well as a search for other solutions. That search has proven difficult, mainly because the top alternative, beach re-nourishment, faces a number of legal and logistical hurdles.

In its responses to inquiries from the HOA, Corps officials have said that adding the area could require redoing the Carolina Beach-Kure Beach re-nourishment plan entirely, which would ultimately require congressional approval.

Adding just the area not already covered by the existing federal project would require costly studies and plans for implementation. Under federal rules, funds for that work and the matching funds for the studies and any possible re-nourishment project would have to come from either the state or local government. To date, neither has shown an interest in picking up the tab.

A memo from the Division of Coastal Management’s legal counsel to the commission in February said that in discussions between Kure Beach officials and the HOA, Kure Beach’s former mayor Emilie Swearingen had said that extending the re-nourishment project would require dissolving the current Carolina Beach-Kure Beach project, which has been authorized through 2047. According to the memo, Swearingen had said the town would not be willing to take on the risk of losing the entire project.

Follow-up conversations between the Corps and Division of Coastal Management officials confirmed the finding.

“Based on this contact, DCM agrees that it is unlikely that the southern end of Kure Beach, at least in the short-term, could successfully be included in the existing federal project,” the memo states. “This is largely because of current funding levels for such projects, the eventual need for Congressional authorization, and because the environmental concerns of federal and state resource agencies, like those raised previously about the coquina rock formations, remain.”

The memo suggests that the main alternative would be to work on a separate re-nourishment project focusing on the area not covered, but it acknowledges that the idea has a slim chance of succeeding in part because of federal funding limitations and because of the environmental concerns over the Natural Heritage Area.

It also throws cold water on the idea that removing the Natural Heritage Area designation would clear the way for re-nourishment. Even if the state were to remove the designation, the environmental concerns about covering it with sand would remain and make it difficult for the project to be approved.

“While removal from this program could be attempted, the site’s de-designation as a Natural Heritage Area would not necessarily alleviate the environmental concerns of resource agencies, including the Corps,” according to the memo.

The next steps for The Riggings are unclear until at least September, when the CRC is expected to review the new provision and how it would impact any future decision.

Until then, as the high tides continue to work away the sand around its only defense against the Atlantic’s relentlessness, The Riggings remains where it has always stood: between a rock and hard place.