ROANOKE ISLAND – Famous – or infamous – for creating “perfectly planned” communities, the three Levittowns created in the 1940s and ’50s were, according to a number of writers, America’s first planned communities.

And, Levitt & Sons, the company that built the towns, advertised them as the absolute best there was.

Supporter Spotlight

“The most perfectly planned community in America,” the 1951 ad for Levittown, Pennsylvania, proclaimed in the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Perfect? That’s subjective … maybe they were, maybe they weren’t. But first? Not even close.

The first planned communities in North America may be the subject of debate, but North Carolina has as good a claim on that as anyone.

Envisioned through legislative action in meticulous detail, a number of early towns along coastal North Carolina could have been 18th century examples of 20th century planned communities.

As the 18th century dawned, North Carolina was the poorest of the British American colonies. Lacking a deep-water port, farmers and merchants in the colony were largely dependent on South Carolina or Virginia ports to import or export anything.

Supporter Spotlight

The Tuscarora War, 1711-1713, devastated an already weak economy. A vicious war, filled with atrocities on both sides, North Carolina was forced to ask South Carolina for help in saving the colony. If not for the aid of their southern neighbor, it is possible that Chief Hancock, leader of the Tuscarora, would have prevailed.

After the war, recognizing that the isolated settlements of the province were vulnerable to attack, the legislature approved laws aimed at creating viable towns.

“It does seem as if there was a concerted effort in the aftermath of the Tuscarora War to create actual towns in North Carolina,” said Brian Edwards, associate professor of history at the College of the Albemarle.

The legislature was also hoping the new towns would become ports of entry, and the language in the legislation was often specific to that goal.

Not all attempts were successful, and no tale of failure quite matches the story of Carteret Town on Roanoke Island.

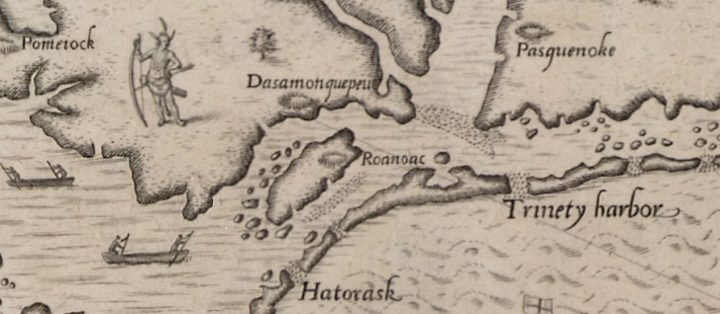

Roanoke Inlet closed permanently around 1810, but in 1715 it was considered an important point of entry to the waters of northeastern North Carolina.

At that time, Roanoke Island was sparsely populated with farmers and fishermen. There was no recognizable town or village, but its location due west of Roanoke Inlet drew the attention of provincial legislators.

In 1715, An Act for a Town on Roanoke Island for the Encouragement of Trade from Foreign parts was passed.

The law is remarkable for the detail it provided for creating the town.

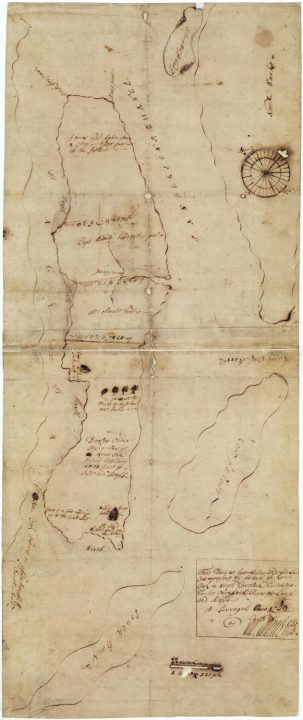

The legislature instructed the Surveyor General to “… lay out three hundred acres of land at Roanoke Island … fronting on the water for the building and settling a Town…” on a site that was near present-day Manteo.The town, Carteret Town as the legislature named it, was to include “… Sixty acres of the said Land fronting on the water …” Residential lots were “… of halfe an acre each … with convenient Squares & places for a Church Publick Town House and a market place with Convenient Streets.”

Wanting to ensure anyone who purchased a lot – the assigned price was 20 shillings – would build on it, the mandated minimum building requirements had a deadline. “Every person or persons whatsoever that by virtue of this Act take up any Lott or Lotts shall & is hereby obliged within twelve months after the Date of Such Conveyance for the Same to build on Such Lott one habitable house at least twenty foot and fifteen foot …”

And, if they failed to build within the one-year limit, “the Conveyance for the same is hereby Declared null & void to all intents & Purposes in Law…”

The 1715 legislation failed to create a town and in 1723 it was repealed and replaced with an almost identical law. That, too, failed.

It’s difficult to point to any one reason why plans for Carteret Town were unsuccessful, although some real estate transactions that were dubious at best seem to have contributed to its failure.

Hoping to simplify transactions and stimulate activity, the legislature would grant the land for a planned town to an individual or group of individuals.

In 1715 the legislature ceded the right to develop Carteret Town to Richard Sanderson of Perquimans County. It is somewhat unclear how much land was given to Sanderson, but there is little evidence he owned the 1,500 acres he sold to William Maule, the Surveyor General of North Carolina, in 1722.

The 1723 legislation was much the same as the 1715 law, including a preference for Sanderson to develop the town. The Lords Proprietors, who still had the final say in the province, felt differently though, and awarded the entire island to John Lovick, who was a member of the general assembly.

Lovick quickly sold his holdings to Sanderson and President of the Provincial Council William Reed, even though there were property owners on the Roanoke Island with clear title to their land.

For Carteret Town there never was much hope. Reed, not satisfied with his land speculation, named himself town commissioner and levied a poll tax on residents for a courthouse that would never be built.

In some ways, however, the failed attempt at creating a port on Roanoke Island was the blueprint for future towns.

Portsmouth came into existence through a legislative act in 1753, An act for appointing and laying out a town on Core Banks near Ocacock inlet in Carteret county.

Much like Carteret Town, the legislation called for a town of 50 acres with half-acre lots, in this case granting 18 months to build on the lots. Unlike the Roanoke Island decree, a town was created.

Earlier, in 1720, An Act for Making a Town at Queen Ann’s Creek was passed, creating a town on 100 acres at the mouth of the Chowan River. When Gov. Charles Eden died in 1722, the town was renamed in his honor.

In 1722, hoping to create a larger city of Edenton, the legislature passed an act for enlarging and encouragement of the town called Edenton in Chowan, that designated lot sizes and required owners to build within a set amount of time or forfeit ownership.

Even today, Edenton retains the streets and some of the buildings from that first attempt to plan a town.