First of two parts

WILMINGTON – For a time it seemed as though last year’s revelation that GenX had tainted the Cape Fear River and downstream drinking water supplies might be a wake-up call for North Carolina to look more closely at the water its residents drink.

Supporter Spotlight

Reports had surfaced in recent years detailing high levels of contamination by substances such as 1,4-dioxane, with health threats far better defined than GenX’s, yet legislators devoted far more attention to paring or weakening environmental regulations and cutting funds for its enforcement.

This time – as GenX-related contamination grew to encompass a host of other fluorochemicals, with pollution found in air and rain, groundwater and private wells, and turning up in a jar of honey – lawmakers seemed poised to take tentative steps toward understanding the scope of water contamination, not just from GenX and other per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, but from emerging contaminants in general.

Certainly, they would not provide funding sought by the governor to begin rebuilding North Carolina’s regulatory agencies, but Senate and House bills responding to alarms about GenX did allocate money to take a broad, open-ended look at contaminants in North Carolina’s drinking water statewide.

At the end of May, though, the North Carolina General Assembly pressed the snooze button on that notion. Lawmakers approved and sent to Gov. Roy Cooper a bill that includes $9.3 million to assess drinking-water contamination but, after learning industry found the original scope “most troubling,” they took care to restrict efforts solely to the class of chemicals that includes GenX.

‘Very Little Has Changed’

A week before that legislative wrangling, North Carolina State University professor Detlef Knappe sat down for an update from state regulators at the Department of Environmental Quality.

Supporter Spotlight

Knappe has been among the most visible of those involved in scientific research to define the scope of contaminants such as GenX emanating from the Fayetteville Works, a 2,150-acre riverside industrial site owned by Chemours. He has spoken at multiple public forums, testified at legislative hearings, conducted further research on filtration methods and contamination in groundwater and food near the Chemours plant, and tried to keep up with torrents of emails from concerned residents seeking information.

This recent meeting with DEQ, however, was not about GenX and the Fayetteville Works. Instead, Knappe wondered where things stood regarding the state’s efforts to address a different emerging contaminant called 1,4-dioxane.

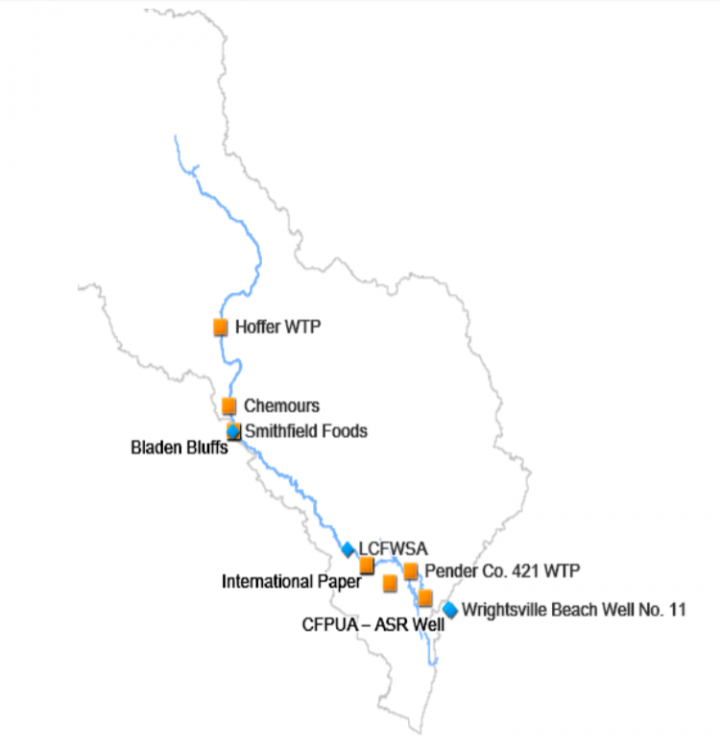

An industrial solvent used in a range of products including paint strippers, pharmaceuticals and shampoos, 1,4-dioxane is “likely to be carcinogenic to humans,” according the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The EPA has established a lifetime health advisory of 0.35 parts per billion in drinking water, a level exceeded in testing at water utilities in several North Carolina communities. Water drawn from the Cape Fear River watershed accounted for seven of the 20 highest 1,4-dioxane concentrations found in the United States as part of the EPA’s most recently completed round of testing for unregulated contaminants in drinking water.

Before GenX grabbed headlines and his attention last summer, Knappe had spent years researching 1,4-dioxane and working with DEQ on steps to identify sources of the contamination and try to reduce their levels. With obvious, sometimes dramatic progress regarding GenX, Knappe was curious: What has happened in the meantime with 1,4-dioxane?

“There was a perception that things had become better,” Knappe said in a recent interview. “I think that perception was maybe the result of some data that suggested that at the known discharger locations Greensboro, Asheboro and Reidsville, that two of them were self-reporting changes that industry had made. And all of that appeared to result in dramatically lower levels of 1,4 -dioxane discharges from Greensboro and Reidsville.”

Last November, having developed a method to analyze 1,4-dioxane to conduct its own testing, DEQ restarted its monitoring program, Knappe said.

“When the state shared those data, I focused primarily on what’s going on in Pittsboro compared to the data we had four years ago,” he said. “My conclusion was that very little has changed. I think they agreed.”

‘There Is Not Yet a New Philosophy’

DEQ has had “very solid” accomplishments regarding the Fayetteville Works and GenX, Knappe said. Since last year, state regulators have issued three notices of violation regarding Chemours contamination and filed a civil complaint in state court.

Under pressure from the state, the company ceased discharging its manufacturing-related wastewater into the Cape Fear, capturing it instead for transport to Texas, where it is injected in deep wells.

In April, regulators told Chemours to “show to DEQ’s satisfaction that they can operate without further contamination of groundwater or we will prohibit all GenX air emissions.” In May, Chemours announced that it had installed carbon bed adsorption technology, part of a promised $100 million investment the company says will eliminate at least 99 percent of air emissions. DEQ has connected those emissions to contamination of hundreds of private wells, some of them miles from the plant, and recently told Chemours to devise a “permanent” solution for people depending on those wells.

“On the GenX front, I think they’re doing a super job,” Knappe said. “All the things I see the Division of Air Quality is doing and Division of Solid Waste is doing and the Division of Water Resources is doing, it’s very solid. They’re trying to cover many bases. I think they’re thinking through all the different aspects of how the contamination is spreading and trying to get as much information with the limited resources they have.”

Knappe said he’s less sure whether similar issues get the same level of attention or what might have happened regarding GenX had it not been reported in the media.

DEQ knew researchers had identified the GenX in the Cape Fear as early as June 2015, when department staff met with company officials to discuss it. What it planned to do with that information remains unclear during the two years that elapsed until June 7, 2017, when the StarNews published the first story online. Requests to interview DEQ Secretary Michael Regan and Assistant Secretary Sheila Holman for this article went unfulfilled.

“One lesson learned is some researcher like me publishing a paper and distributing the paper widely is insufficient. It really takes the media to disseminate the information and then the general public and elected officials all pulling on the same string.”

Detlef Knappe, Professor of civil, construction, and environmental engineering, N.C. State University

A review of DEQ records regarding its work at the Fayetteville Works during those two years revealed none of the GenX-focused water sampling, site visits and other enforcement-related measures that started in June 2017. In a letter to the EPA, Gov. Cooper wrote that state regulators launched their investigation into the matter June 14, 2017.

By September, after GenX turned up in several of Chemours’ monitoring wells, DEQ had issued the first notice of violation and filed a civil complaint against the company.

“One lesson learned is some researcher like me publishing a paper and distributing the paper widely is insufficient. It really takes the media to disseminate the information and then the general public and elected officials all pulling on the same string,” Knappe said.

By revisiting the situation with 1,4-dioxane, Knappe sought to “test the waters a little bit to see whether anything has really changed. I’m not fully convinced it has, not in a proactive way. There is not yet a new philosophy that’s pervasive in DEQ or DHHS (Department of Health and Human Services) or in the legislature.”

‘It Often Takes a Big, Ugly Crisis’

Others have different perspectives. Robin Smith, a Chapel Hill environmental lawyer, spent 12 years as an assistant secretary for the environment at DEQ’s predecessor, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources.

“I will say, from what I know about how this bubbled up initially from the results of the study being reported to DEQ and EPA, my sense is there was not a lot of context for the information in the beginning,” Smith said, referring to the scientific research study on GenX in the Cape Fear. “GenX was not something that was in the (discharge) permit. It was not something the regulatory staff was looking for. When the study was done, because there was not a health study or drinking water standard for GenX, there was not a context to put the issue in.

“Ultimately, the health advisory levels were developed by DHHS, which gives you a benchmark to figure out: ‘Well, is this a good number or a bad number?’ If you don’t have a standard to compare it to, it’s a little difficult to know what to do with it.

“I don’t think they had lost track of it entirely,” Smith said. “There was an intention to go back and pull together folks to try to understand what this meant. And then this thing took off.”

“I recognize that DuPont’s permits have been issued by Democratic-controlled DEQs just as much as Republicans, so in that regard, we failed on those permits across the board, no matter who was in control.”

Kemp Burdette, Cape Fear Riverkeeper

As for DEQ’s approach before last summer and after, Smith said, “I don’t know that I have seen changes so much. Enforcement, especially on a big complicated issue, is a progression through a number of steps, like in this case, when they discovered that air emissions were a big part of the problem. They seem to be following all the normal steps, pursuing groundwater contamination and air emissions. It’s typical for a messy enforcement situation.”

Cape Fear Riverkeeper Kemp Burdette said he’s “pretty pleased in general with the way DEQ responded from last September on. I think they’ve started to take this situation pretty seriously.

“I recognize that DuPont’s permits have been issued by Democratic-controlled DEQs just as much as Republicans, so in that regard, we failed on those permits across the board, no matter who was in control.

“I haven’t seen any kind of memo that’s been sent around that says, ‘we’re going to re-evaluate all these permits,’ but I feel like the agency has been rocked by GenX. I think, in general, the folks at the agency think this is a problem that they are behind on, and they need to be thinking about it.”

Smith said DEQ’s overall approach to regulation largely reflects the political environment in which it operates.

“It’s often less about the agency staff than it is about the signals being sent by legislators and sometimes the governor’s office. The agencies know who they work for. This is rarely about what they personally would like to see happen than it is about the political universe,” she said.

“At what point is the majority of that political universe willing to do something significant? It often takes a big, ugly crisis to get there.”

Knappe acknowledged political pressure is the “other elephant in the room. I’m sure there are a bunch of people (at DEQ) who would be more proactive if the repercussions wouldn’t be so bad.”

Regulators in North Carolina function in a fluctuating political environment but one where lawmakers, overall and in a fairly bipartisan way, have tended to look sympathetically on the interests of business.

“Democratic or Republican, it’s always been a business-friendly legislature,” Smith said. “Governors and to some extent legislators have differed in terms of their willingness to take tough steps, but those tough steps almost always came in response to something approaching a crisis situation like GenX.

“We went through something very similar with hog farms back in the 1990s. I think generally there’s a desire on the part of the legislature to be business-friendly and concerned about the economic impacts of cracking down on an industry, especially if it employs a lot of people. Then a situation blows up, and it becomes clear that there’s a need to take strong action.

“We’ve been down this road before. It’s an interesting case study in how a legislative philosophy bumps up against a real-world problem.”

‘Many Chemicals in Those Water Supplies’

That business-friendly approach was on display last month as measures to deal with GenX evolved in legislative negotiations.

Before incorporating the GenX-related measures into the final budget-adjustment bill, lawmakers agreed to changes urged by the North Carolina Manufacturers Alliance, WRAL.com reported.

The alliance is a lobbying group of more than 50 companies, including GenX manufacturer Chemours. It requested the removal of references to the state’s 140-parts-per-trillion health advisory for GenX. It wanted clarification on a provision requiring companies to release detailed information about the chemicals they discharge into state waters under permit. The alliance also singled out the portion it deemed “most troubling,” one that would have taken a broad snapshot of drinking water statewide and scrutinized its contents.

In a letter to legislators obtained by WRAL, alliance President A. Preston Howard Jr. wrote: “Possibly the most troubling provision of the bill is the provision that tasks the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory and DEQ with sampling all of the local government water supplies and conducting non-targeted analysis on those samples. I feel comfortable saying with some certainty that this high-resolution analysis will most assuredly reveal that there are many, many chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and other consumer products in those waters supplies. Most will be detected at very low levels. But just as was the case with GenX, there will be very little information about the toxicity of those substances, resulting in the same or similar controversies over whether the concentrations pose any significant risk to public health or the environment. The expanded scope does nothing more than open a Pandora’s box on emerging contaminants.”

All three requests are reflected in the final text of the budget-adjustment bill, which makes clear its fluorochemical focus and other restrictions in several sections. For example, the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory will receive $5 million to coordinate research at the state’s universities, but only on PFAS such as GenX.

DEQ will get a mass spectrometer capable of conducting “targeted” analysis rather than the one it had sought, which would have been capable of “non-targeted” testing.

Targeted analysis involves looking for a specific, known substance. It answers the question: Is this in the water? Non-targeted analysis is more flexible, revealing substances in water samples even when researchers may be unsure what they are looking for. The question is more open-ended: What is in the water?

“While I am disappointed that the language in the bill was changed from the broader focus on emerging contaminants to the more narrow focus of PFAS, I can argue that it is a first step in the right direction,” said Knappe, who is helping lead a collaboratory-funded program announced in April to determine resources needed to establish what he called an “observatory” for water contaminants.

“The bill provides universities across the state and DEQ with funding to establish a collaborative framework to study PFAS occurrence in drinking water sources. By studying all public water systems across the state, residents will learn whether PFAS are present in their drinking water sources. Non-targeted analysis is becoming more and more routine, meaning it will become impossible to keep one’s head in the sand.”

For Smith and others, the provision makes clear that the legislature remains reluctant to invest in the state’s regulators.

“The provision in the bill that has to do with obtaining a mass spectrometer has specifications that are not as sophisticated as what DEQ asked for,” Smith said. “It doesn’t seem to be a money issue, but there continue to be ways in which the GenX provision keeps holding back funding (from DEQ) or sending it in another direction. That’s been a very clear trend throughout the past year.

“To me what’s happened over the last year has looked for a while like tension largely between the House and the Senate, but the Senate seems to be particularly wary of authorizing additional actions by the department and appropriating additional funds to the department. They’ve moved somewhat in terms of GenX, but it’s hard to see that carrying over more broadly into water quality issues.”