NORTH TOPSAIL BEACH – There were no signs. No fence posts and ropes. No blatant, visible barriers.

Invisible boundaries set apart the families who vacationed in Ocean City, a mile-long stretch of land within North Topsail Beach believed to be one of the first beachfront communities owned by African-Americans.

Supporter Spotlight

The whole concept was, during that time nearly 70 years ago, a radical idea dreamed up by Edgar L. Yow, a white Wilmington attorney, and developed by Wade H. Chestnut Sr., who sold his interest in the family’s auto repair business in Wilmington to build the beach community for his and other black families to enjoy.

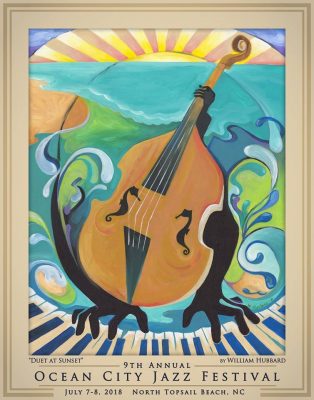

Those dreams-turned-reality are being celebrated during the ninth annual Ocean City Jazz Festival, a two-day event designed to draw people of all walks of life together through music to help keep the community thriving.

The festival commemorates the 1949 establishment of Ocean City, where anyone is welcome to come out July 7-8 to 2649 Island Drive, North Topsail Beach, and enjoy the variety of jazz musicians.

“I believe that for me and my generation, we need to be stewards of what we are left with,” said Kenneth Chestnut, Wade’s son. “We’ve been entrusted to something that is very special.”

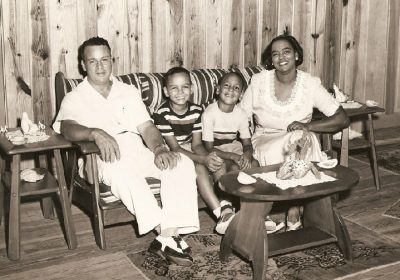

He was a toddler when his parents first visited Topsail Island.

Supporter Spotlight

This was years before North Topsail Beach incorporated, before the housing boom, when little oceanside cottages sparsely dotted the 26-mile-long barrier island and the only access was by a floating pontoon bridge.

Kenneth Chestnut, who is also a member of the North Carolina Coastal Federation’s board of directors, spent his childhood summers playing on the sandy shores mingling with children whose families left their permanent homes in places like Wilmington, Durham and Raleigh for their beach refuge.

“It was a close-knit community,” he said. “There was a connection with people that primarily lived there during the summer. It was a great place for developing friendships and relationships.”

They’d swim and go crabbing. Families shared dishes of crab gumbo and deviled crab made from fresh catch. In the fall, families would get together for oyster roasts.

They’d cook together and eat together, cementing the principle that Ocean City, built to be a family-oriented community, would stay as such.

Kenneth Chestnut remembers working with his dad on the Ocean City Fishing Pier, where the common goal to cast and catch blurred the lines of segregation.

“The fishing pier was very much integrated,” Kenneth Chestnut said. “People from all walks of life and all races fished together on that fishing pier. People were just centered around the effort of catching fish.”

Hurricane Bertha destroyed the pier in 1996.

Before Bertha, there was Hazel, the strongest and only Category 4 hurricane to hit the North Carolina coast.

Hurricane Hazel wiped out Ocean City’s original homes built by Fayetteville contractor William Eaton.

The home he built for his family on the $500 lot he purchased across the street from oceanfront properties in the community was a helpless heap in the sound after Hazel’s lashing.

“He was determined that the next one he built would stay and I’m proud to say it’s still there,” said his daughter, Carla Torrey.

Torrey cannot recall how her father was introduced to Ocean City, but she does know he built a majority of the original homes.

“During the summer we would stay down so he could build,” she said. “My father would bring his crew down and they would stay at the house and work during the week. During the weekends my mother would come, and we’d have family weekends.”

William Eaton built more than 50 homes, a motel, chapel and dormitories for the Episcopal camp for African-American children.

Torrey remembers “having a lot of eyes” on her, other adults in the community who steadfastly kept a lookout on the children playing in the ocean.

“I particularly remember Mrs. Chestnut. She would always keep an eye on me when I was in the water,” Torrey said.

Days in and around the cottage-style, split-level, two-bedroom home were filled with family, food and laughter.

“I tell my husband that I was not in any way aware that it was something unusual or that I shouldn’t have been there,” Torrey said. “I never really had a sense of the magnitude of what it was. I never knew that it was an oddity.”

As she grew into her teenage years in the age of the civil rights movement, that’s when she noticed it. She would be on the beach and look to the right and to the left, past that invisible line, and see where white beachgoers congregated.

“I’m very proud of Ocean City and it’s kind of driven my husband and I to become involved in the community organizations to try to promote the history of the community,” Torrey said. “I think there are a lot of layers to it. I think it took a lot of foresight for my father to buy into a community like that because it didn’t exist. They had to have a sound plan of what they wanted to see. I think they really accomplished that. On the other hand, I see that even if there was not complete inclusion there was tolerance and I think that says a lot about that community. I think we have a really rich history and I very much hope that we can preserve it.”

Wade Eaton lived to the ripe age of 98, long enough to see the day when, in the mid-2000s, he was offered a cool $1 million for his island property.

He politely declined the offer.

“It was very much a part of him,” Torrey said. “I don’t think any amount of money would have made him give it up.”

Torrey has had conversations with her son about the importance of keeping the property in the family.

Ocean City was added to the Jacksonville-Onslow County African American Heritage Trail in May 2014. Two years prior, the North Topsail Beach Board of Aldermen paid for the installation of several commemorative street signs featuring an Ocean City logo for streets within the community.

For more information, including ticket purchases, parking and transportation to the Ocean City Jazz Festival go to http://www.oceancityjazzfest.com